This week we launched ODI’s new Future Development Goals Tracker. This is an exciting tool for post-2015 watchers, since it brings all the proposals for future goals together in one place and allows you to search for what’s been said in your areas of interest. We’ll be putting out more analysis soon to help make sense of it all, but with ‘a good education’ shaping up as the top post-2015 priority according to the first MyWorld global survey results, here’s an early look in at what the Tracker tells us about proposals in this crucial sector.

This week we launched ODI’s new Future Development Goals Tracker. This is an exciting tool for post-2015 watchers, since it brings all the proposals for future goals together in one place and allows you to search for what’s been said in your areas of interest. We’ll be putting out more analysis soon to help make sense of it all, but with ‘a good education’ shaping up as the top post-2015 priority according to the first MyWorld global survey results, here’s an early look in at what the Tracker tells us about proposals in this crucial sector.

Of the 160 or so post-2015 proposals we’ve found so far (that includes full proposals across goals, framework approaches, plus ideas for goals sector by sector), 11 focus on education or skills. Among these there are clear differences but on the whole a strong degree of overlap on what future education goals could usefully address. All of them put forward ideas for expanding on our simple but inadequate MDG2 on Universal Primary Education…so education post-2015 is shaping up to be as ambitious as it is important.

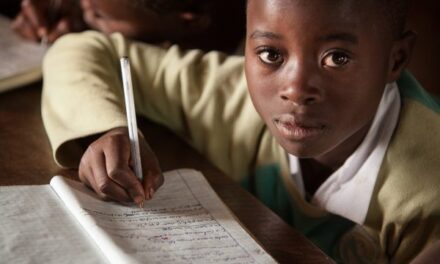

And there’s quite some overlap on the areas that proposals suggest expanding into: most mention pre-primary or post primary education (in addition to primary), and adding quality (‘learning’) to the MDG2 access objective. But only around half of the proposals have some focus on skills linked to productive employment (as opposed but not unrelated to life skills). It could be that productive skills will be addressed elsewhere in a post-2015 agenda – tackled for instance in goals on employment – leaving an education goal the space to focus on the core business of quality education for all, be it at primary, post-primary and (or) pre-primary levels. This in itself holds mighty ambition. But considering the importance of expanding employment opportunities post-2015 – which relies in significant part to young people having the right skills to better link to these opportunities – it’s crucial that an agenda on skills finds its space in any new framework, if not through a goal on education, then elsewhere.

A scan across the proposals also reveals that the education sector is already grappling head-on with the central questions of inequality and inclusion post-2015, in the wake of our collective disappointment over how many continue to be left behind in spite of progress overall on MDGs 2 and 3. New proposals rightly highlight that designing the measurement of future targets and indicators in a way that incentivises action on the ‘for all’ part of an education goal, will be key to setting inequalities in education access (and learning) straight. Save the Children and Results for Development Institute recommend monitoring progress by wealth quintile to do this, and others like the Global Campaign for Education and the Basic Education Coalition suggest doing it by disaggregating by gender and a range of other marginalised or vulnerable groups.

With a world of work already cut out for any ‘MDG plus’ future agenda on education, complex methods of disaggregation that try to address too many groups might just prove too much, not least because this goes well beyond the present statistical capacities of most countries. That said, to fix the MDG progress gap that’s left behind the poorest, at least one additional layer of measurement, by wealth quintile on top of gender, will be crucial if countries are to begin fighting inequalities with the help of a new education goal. More work is needed to get this right, because as our MDG experience tells us, finding realistic but effective measures for inclusion is something we can’t afford to get wrong this time around.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks