20th November 2014 marks the 25th anniversary of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). It is a time to look back and celebrate advances in children’s rights over the past quarter of a century. But it is also a time to take stock and recognise the continuing challenges facing children in a globalised world.

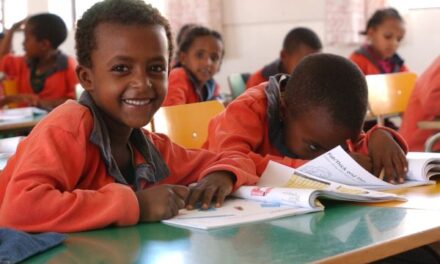

Agizo, 10, attends NRC’s Education programme at a primary school in Masisi, for children displaced by conflict, in Masisi, North Kivu, DRC.

Copyright: Jonathan Hyams/Save the Children

Conflict not only keeps children out of school, it also reverses gains that have already been made. Before the war in Syria, nearly all children were enrolled in school. Four years into the conflict almost 3 million Syrian children are being denied their right to education. Escalation of violence in the Central African Republic led to schools being open an average of just four weeks in the first six months of the 2013-14 school year. In Iraq, over half a million school-aged children have been displaced by violence since January. These are but a few examples.

Children’s right are universal. They apply to all children irrespective of context. As we remember the vision for children’s education enshrined in the UNCRC we must also look forward and ask how more can be done to protect and fulfil the right of all children to receive a good quality education, even in times of conflict. The twenty-fifth year of the Convention provides us with an opportunity to do just this.

The ‘Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict’, to be launched next month, provide a useful tool for safe-guarding education during war time. Research by the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack has shown that in the majority of contemporary conflicts around the world, military forces and non-state armed groups have used schools and other education institutions as bases, barracks, firing positions, munitions stores, detention centres and even torture chambers. Unsurprisingly, the presence of troops in schools often leads to children dropping out, reduced school enrollment, lower rates of transition to higher levels of education, loss of motivation or absenteeism by teachers, and overall poorer educational attainment.

The Lucens Guidelines draw on international human rights and humanitarian law, as well as good practice, to provide concrete guidance to states and non-state armed groups on how to reduce the use of schools and universities by armed parties and to minimize the negative impact that armed conflict has on students’ safety and education. As such, endorsement and implementation of the Guidelines provides a concrete step which governments and non-state armed groups can take to support the right to education of children living in the shadow of conflict.

Meanwhile, in 2015 two important processes conclude, which will set the course for government investments and worldwide efforts in education over the next 15 years. These are the revision of the Education For All agenda and global agreement of new sustainable development goals. Worryingly, proposals to date for each of these frameworks have been markedly ‘crisis-blind’. As we have seen recently in Syria, the Central African Republic, Iraq and many other places, the disruption of education in humanitarian contexts has significant implications on children’s ability to access their right to education and can seriously undermine educational progress. A post-2015 education framework must be crisis-sensitive if it is to effectively address the challenges facing the fulfilment of children’s right to education in the 21st century, not least the challenge posed by conflict.