Reflecting on the recent Higher Education and International Development Forum, Susy Ndaruhutse and Charley Nussey (CfBT Education Trust) ask whether higher education has something more to offer – or if it’s just a product for the wealthy.

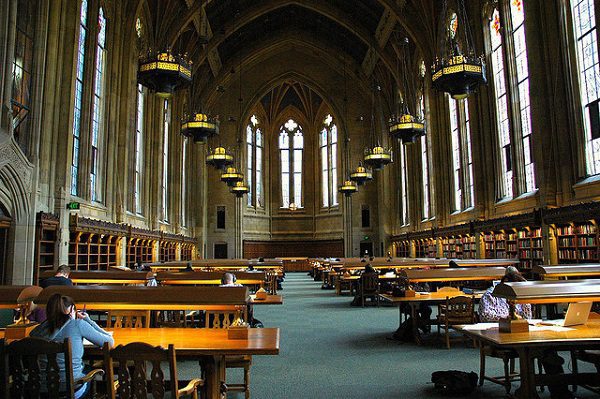

At end of October, The Education and Development Forum (UKFIET) sponsored a Forum on Higher Education and International Development, co-convened by Tristan McCowan and Rebecca Schendel at the Institute of Education, London. The 100 or so attendees were mostly academics, but also some practitioners, students and donors. As Simon McGrath noted in his opening comments at the Forum, higher education is rightfully growing in importance in development discourses, and starting to take its place on global agendas.

New resource: Summary of Workshops from the October Forum now available.

Rajani Naidoo opened the Forum with a thought-provoking and stimulating discussion of some of the tensions that exist in the discourse today. She questioned the equity implications of higher education. In many contexts higher education has become, for the wealthier, a ‘product’ that can be purchased and globally ranked. This ‘stratifies’ access, cementing a global elite with better employment opportunities and access to social goods, and a relatively higher social position than those who don’t have access.

However, she also spoke of the potential of higher education students and institutes to hold a relative degree of autonomy. A powerful example of the transformation of higher education is the Cuban approach to medical education. This embeds doctors strongly within local communities, with a humanitarian approach that has challenged gender and class norms. Such approaches pose alternatives to some of the established ‘truths’ about how higher education can be provided, and to whom.

The tensions that Professor Naidoo raised around power, the role of elites for both good and bad, and the possibilities of social mobilisation, were all live issues in one of the day’s later parallel sessions, which focused on the relationship between higher education, student development, and national development. An accepted premise underlying our discussions seemed to be that we are not happy to think of higher education in terms of the development of skills and human capital alone. Whilst this is important, each of our speakers took us beyond skills and into the need to capture the full effect including questions of values, reform coalitions, innovation, and increasingly globalised student identities.

One question in particular seemed to capture our concerns – how do universities promote and develop critical thinking without coming into conflict with the State? There is evidence of a strong positive correlation between higher education and good governance, but we need to know far more about how we should attribute causality, and what forms of higher education best promote both individual wellbeing and strong States. Our work with the Developmental Leadership Program aims to continue to try and answer these questions.

At the end of the discussions, we were in no doubt that higher education plays a necessary, although not sufficient, role in national development and should be an integral part of the post-2015 Sustainable Development agenda. As global inequality, youth bulges and concerns about creeping forms of neoliberal ideologies come to the fore, the importance of a highly educated cadre of citizens who can speak truth to power is all the more central.

You hear a lot about the financial ramifications of income inequality: difficulty saving, major gaps in overall wealth accumulation, and a shrinking middle class. But the gap between America’s richest and poorest families also has a major impact on the ability to achieve educational goals, which can create long-lasting and detrimental consequences for low-income families.

A recent study from the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education and the University of Pennsylvania Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy (AHEAD) took a look at the educational achievement of students aged 18 to 24 from different income brackets over the past 45 years. The researchers found that when it comes to completing higher-education degrees, the gap between the rich and the poor has actually grown significantly.

And there’s a way for richest https://essaycool.com/ but what remain for poor students? Them remained be smart how you think?

I think that all education need to be free or need to be given smartest not richest because there will be only degradation of nation.

Around the world it is true, but talking to USA, a developed country, this thing is rare.. But what is all require for the higher education is the Financial Support