This post is based on a paper presented at the UKFIET 2017 conference by Tassew Woldehanna, Pauline Rose and Caine Rolleston. For the 2017 UKFIET conference, 23 individuals, including Tassew, were provided with bursaries to assist them to participate and present at the conference. The researchers were asked to write a short piece about their experience.

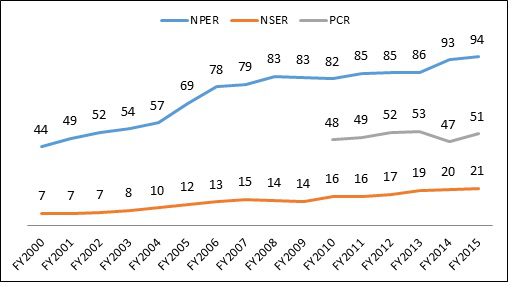

Primary enrolment has expanded dramatically in Ethiopia over the past 20 years, with the net enrolment rate for primary education increasing from 44% in 2001 to 93% in 2015. Growth has been particularly high in the emerging regions and among more disadvantaged groups who were previously left behind; this has also been accompanied by impressive poverty reduction across the country.

Primary enrolment has expanded dramatically in Ethiopia over the past 20 years, with the net enrolment rate for primary education increasing from 44% in 2001 to 93% in 2015. Growth has been particularly high in the emerging regions and among more disadvantaged groups who were previously left behind; this has also been accompanied by impressive poverty reduction across the country.

The General Education Quality Improvement Package (GEQIP), a large-scale, government-led reform, has included a strong focus on improving and maintaining the quality of education in Ethiopia since 2009. However, although strategies associated with the reform have received considerable political backing, it is not clear that they have had the desired impact on system efficiency and education quality.

Over the next five years, RISE Ethiopia will aim to understand coherence in the design and implementation of GEQIP, as a means to evaluating the extent to which GEQIP reforms have raised learning outcomes equitably. This post explores some of the available evidence on learning outcomes in Ethiopia, and considers key questions for RISE based on this evidence.

Rising access, but low system efficiency and poor learning outcomes

As in many countries, primary completion and progression remain low in comparison to initial enrolment in Ethiopia (Figure 1). Grade repetition rates have remained fairly constant (8% in 2009, 7% in 2014), while the drop-out rate has decreased over the same period from 19% to 10%. More disadvantaged students continue to be more likely to drop out of school, with reasons for dropout including children needing to work to support their families, illness in the family, long distances between home and school and a lack of resources to cover school expenses.

Figure 1: Net primary and secondary enrolment rates (NPER and NSER) and primary completion rate (PCR), 2000 – 2015 (Ministry of Education, 2017)

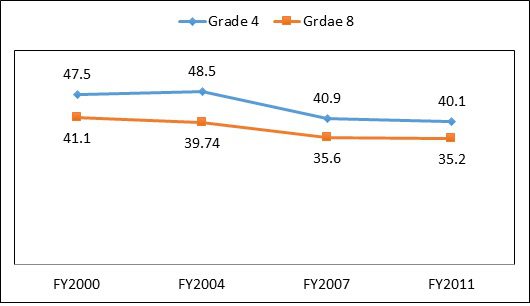

Recent results from Ethiopia’s National Learning Assessment indicate low levels of achievement in reading, maths, science and English in Grades 4 and 8. In 2011, the national composite mean score for these subjects was less than 50%, which is the minimum achievement level set by the Ministry of Education (Figure 2). Learning outcomes appear to have stagnated and, if anything have declined over time (particularly in maths). This pattern has also been observed in the Young Lives Ethiopia study.

Figure 2: Trends in composite National Learning Assessment mean score (%), Grades 4 and 8 (Woldetsadik, 2013)

Explaining poor learning outcomes in Ethiopia: what do we know already?

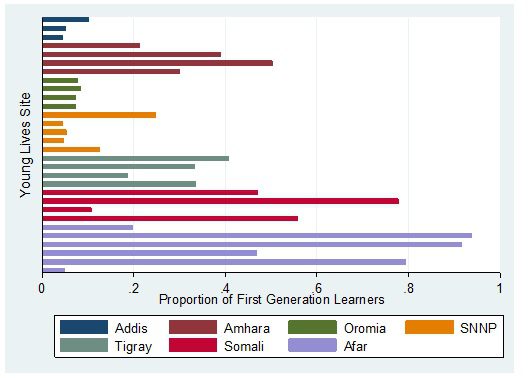

How far can existing evidence help us to explain poor learning outcomes in Ethiopia? Our analysis of data from the Young Lives upper primary school survey in Ethiopia (conducted in 2016-17) indicates that overall stagnation and decline in learning outcomes may be due to the changing composition of school populations as access has increased. First generation learners (defined as neither parent has ever been to school and neither parent can read or write) in the Young Lives school survey scored significantly lower on maths tests in Grades 7 and 8, and made significantly less learning progress than their classmates over one academic year. Meanwhile, children whose fathers have never been to school are overwhelmingly concentrated in the pastoralist regions of Afar and Somali and in rural areas; the proportion of first generation learners ranged from 10 % in Addis Ababa survey sites to 90% in Afar sites (Figure 3).

To what extent are system expansion and the associated inclusion of students from more diverse backgrounds behind stagnant and declining learning outcomes in Ethiopia? Forthcoming analysis of available data will explore this in more detail. It is apparent that the composition of the school population has changed as access has increased, but at the same time, per pupil spending appears to have remained low.

The balance between quantity (growth in access) and quality (resources, progress, learning outcomes) presents a challenge for equitable provision of education; while growth reduces inequality on the dimension of access, increased diversity of children entering the school system for the first time may lead to greater inequality with respect to the quality of schooling accessed by more and less advantaged groups.

Through its focus on understanding the design, implementation and effect of the GEQIP reforms, RISE Ethiopia will examine whether specific interventions are suited to accommodate diverse populations entering the education system. For example, one aspect of the reforms is associated with the expansion of pre-primary education. Has this been designed in a way that addresses learning gaps between first-generation learners and those from more advantaged backgrounds when children enter primary school? Are curriculum reforms designed to ensure children who make slower progress in literacy and numeracy are able to reach minimum standards by the time they leave school? By understanding whether, how and why specific reforms have had effects on learning outcomes, RISE Ethiopia will provide unique evidence on the equity implications of rapid system expansion, which in turn will be used to inform future policy developments in Ethiopia and internationally.

Thanks for Articles.