UKFIET organised a consultation meeting in London on 22nd May 2017 around the 2019 GEMR on Education and Migration at the request of the GEMR team. This blog reflects some thoughts from Kenneth King, University of Edinburgh and NORRAG Kenneth.King@ed.ac.uk

UKFIET organised a consultation meeting in London on 22nd May 2017 around the 2019 GEMR on Education and Migration at the request of the GEMR team. This blog reflects some thoughts from Kenneth King, University of Edinburgh and NORRAG Kenneth.King@ed.ac.uk

The plan for the Global Education Monitoring Report (GEMR) to review education and migration in its 2019 report is very timely, but also hugely ambitious (see the Concept Note). Migration has been one of the most politically sensitive issues in many countries in the very recent period – including in USA and in several EU member states. But it is also an area more generally where the discourse about migrants is urgently in need of greater clarification.

Who are we talking about?

It is therefore good to see in the Concept Note that there will be some serious discussion of ‘concepts, definitions and distinctions’. Significantly, the 2019 report will not focus just on involuntary or voluntary migrants, or on refugees versus economic migrants. It will cover all of these. And it will do so because there are no longer any simple, sharp distinctions between these categories as there may once have seemed to be.

For instance, young people in situations of grinding poverty, with agriculture increasingly affected by climate change, may feel they have to try migration even if they are not oppressed politically. Does this make them ‘voluntary’ or ‘involuntary’? Similarly, refugees crossing the Mediterranean may sometimes appear to be economic migrants since they are very clear about which European countries they are targeting and for what reasons. They are not just asylum seekers, happy to remain in their first destination. There are many other issues to clarify such as ‘Southerners’ who are long-term residents in the ‘North’, and vice versa, and the awkward term, ‘expatriate’.

Reviewing international student mobility, voluntary and involuntary migration, refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) in the same report is going to be an enormous challenge, but, arguably, it is vitally important to cover this whole landscape of migration so that foreign students, migrant workers, and refugees are clearly and directly connected to the pressures of globalisation, and to increasing awareness of identities through social media. Hence clarifying who is a migrant (international, regional or internal) and what are the drivers of their movement (political, economic, social) is vitally important.

The long-term histories of migration

Migration is a sharply contemporary, political issue in many countries. But it is vitally important to acknowledge that in the histories of migration, whole cities, countries and continents have been re-peopled, and earlier peoples decimated or marginalised. History is also important in underlining the fact that becoming a refugee is often a very long-term experience. The Palestinian refugees have now been in camps for 70 years, and the refugees from Rwanda to Uganda were there for 30 years. Many thousands in refugee camps around the world can anticipate being in these for at least 10-15 years.

Even rural-urban migration within a single country may involve long-term situations of one family-two households for much of their working lives. The same is true of regular, long-term male migration for work in the Gulf. Equally, international student migration may well involve young people studying abroad for almost 10 years, to secure under-graduate and post-graduate qualifications. This is particularly the case for the large number of small states which don’t have sufficient higher education opportunities locally, and which therefore operate as ‘export’ or ‘migration regimes’.

What will become clear in these histories and present realities of migration is that South-South, rather than South-North, migration has been the dominant modality, meaning that no less than 86% of migration is from one Southern country to a neighbouring Southern country (UNHCR, 2015).

Connecting migration to the SDGs and particularly SDG4

As this particular GEMR, of course, will be connected to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and particularly to SDG4, it is important to recognise how migration, both voluntary and involuntary, are actually discussed in the SDGs. For comparison, the terms ‘migrants’ and ‘refugees’ appear in the World Declaration on Education for All in 1990, and there is a whole paragraph of its Background Document, Meeting Basic Learning Needs: A Vision for the 1990s on supporting education for refugee populations (Section 1Biii, p. 56). By contrast, these terms don’t appear in the SDG4 targets at all, and the only SDG with a reference to migration is SDG10 with its commitment to ‘reduce inequality within and among nations’. In that Goal, there is an important target (10.7): ‘Facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies.’

This may seem a world away from the current realities of migration, and almost the opposite of ‘orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration’. But the UN SDG document, Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development (2015), does contain a key, very strong paragraph (29) on migration which includes the following lines:

We recognize the positive contribution of migrants for inclusive growth and sustainable development. We also recognize that international migration is a multidimensional reality of major relevance for the development of countries of origin, transit and destination, which requires coherent and comprehensive responses.

SDG4, arguably, does have one reference to migration: ‘By 2020, substantially expand globally the number of scholarships available to developing countries’ (SDG4.b). This target is particularly aimed at least developed countries, small island states and Africa. And it aims at higher education, vocational training, engineering and ICTs. What is not said, of course, is whether this scholarship agenda is actually a call for brain drain. The reality is that even if developing countries themselves seek actively to promote high quality vocational training, engineering and ICTs, but if there is no corresponding employment opportunity created in the countries themselves, this too is an agenda for migration.

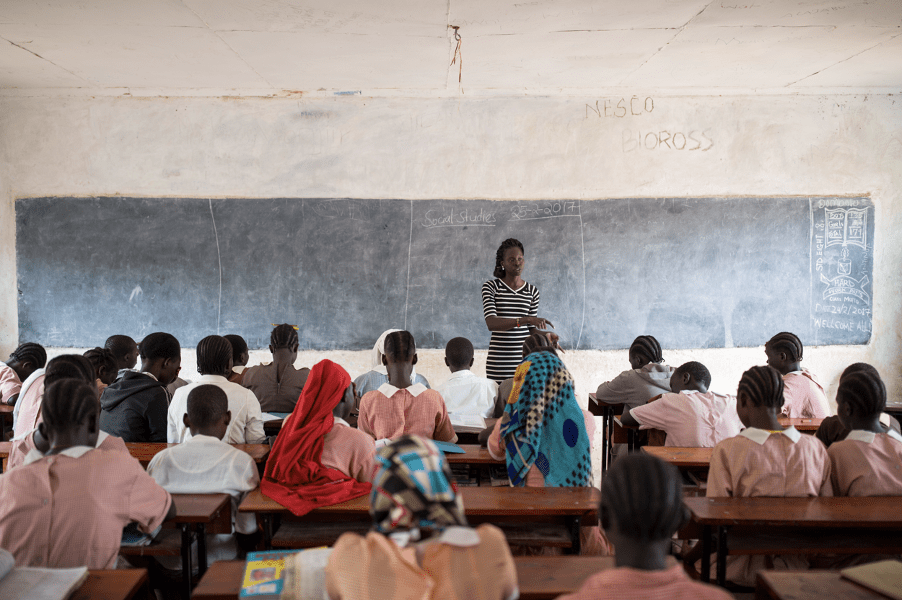

Though schools and colleges are not mentioned in SDG4 as mechanisms for dealing with migration, they are one key element in insuring that ‘no one is left behind’ which is a core pledge in Transforming our world: ‘As we embark on this great collective journey, we pledge that no one will be left behind’ (paragraph 4). Refugee migrants, sitting for years in camps, or not accessing education at all, which is the sad reality of much migration, is a clear connection to this pledge of leaving no one behind.

But even the encouragement of many more scholarships to study abroad can have an impact on national systems of education. Arguably, scholarships are a part of the globalisation of education which is potentially dangerous to national institutions and their qualifications.

Clearly, a 2019 GEMR, wholly dedicated to education and migration, would be crucial to our better understanding of one of the most important issues of our time.

The Report will also present evidence on the scale and characteristics of different types of migration, and national differences in migration policies and patterns in relation to education.