Capturing data on teachers as professionals, learners and change-makers in low resource contexts

Rhiannon Moore (University of Oxford), Alison Buckler (The Open University), Eric Addae-Kyeremeh (The Open University), Renu Singh (Young Lives, India), Jack Rossiter (University of Oxford), Chris High (Linnaeus University)

When we picture a school, many of us will see a teacher, standing at the front of a classroom. When our children are at school, it’s their teachers we turn to with concerns. When we think back to our own school days, we think fondly about our favourite teachers, those who really stood out. Teachers have always been at the heart of education, at least in the popular imagination. It is particularly odd, then, that in much of the education research and policy discourse in low-income countries over the past 20 years teachers have been side-lined and presented as passive, generic (and often negative) inputs. While children’s engagement with education systems is increasingly framed in constructivist terms, with much attention given to the interrelation between their ideas and their experiences, these terms have been far less evident in research and policy around teachers’ engagement with these same systems.

This is slowly changing, and for the first time global goals recognise the central role of teachers. We intend to use this blog post – and the UKFIET September 2017 symposium it links to – to acknowledge and critically consider this change, what it signifies and how our work can support and strengthen this recognition: What do we do when, as educational researchers, we want to learn more about teachers’ knowledge and experiences, and the roles they inhabit? What methodologies can expand our understanding of the working lives of teachers? To what extent should we include teachers in the design and analysis of these methodologies? What ethical considerations do we need to undertake and what logistical and empirical challenges might arise? And crucially, how can we try our hardest to ensure that data collected will support and empower the teachers we study?

A recognition of the teacher as knowledgeable and agentive

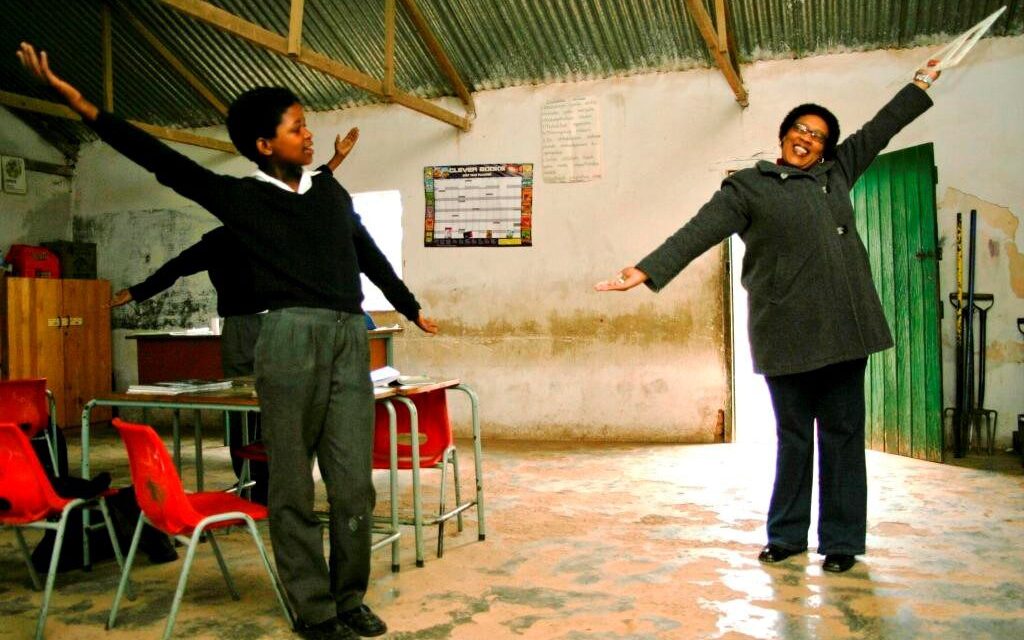

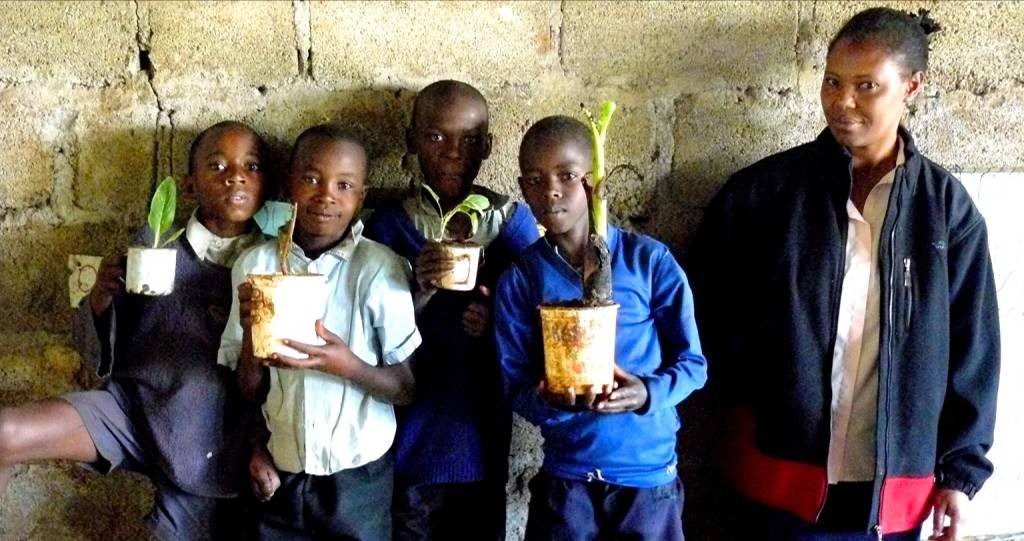

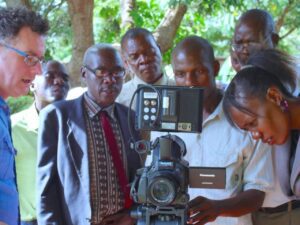

The participatory and visual methods pilot in Malawi was conceptualised as a co-investigation between NGOs, academics and teachers and designed in in way which foregrounded participants’ collective sense making of their experience; over a 3-week period, the teachers were provided with the technology and technical support to make a film about teaching in their schools. The intention was that different viewpoints on education would come together at the locus of the research rather than prior to and retrospectively. While we appreciate that the varied agendas and funding priorities underpinning research mean that participatory approaches cannot always be embedded in the design, a recognition and valuing of teachers’ perspectives was present across all four studies. For example, within the social network analysis study in Ghana, the incorporation of interview and observations within this approach offered the opportunity to capture the head teacher voice, which was crucial in examining the structural web of interrelationships and the quality of associations and how these afford access to ideas, resources, learning and influence.

A recognition of the importance of context and connections

The social network analysis of head teachers’ professional networks in Ghana situates head teachers within a geographical and inter-personal network by its very nature. But all four studies included a focus not only on the teacher as a professional, but as a professional interacting with and within their specific environmental and social-cultural contexts. Within the cross-country school effectiveness survey, the linked nature of the dataset generated means that teacher experiences can be placed within the context of the school they are in and the students they are teaching; essential for understanding more about the complex relationships between teacher knowledge, beliefs and practices, student learning, and school management. Likewise, in the teacher demand and supply study in India, the methodologies used drew both teachers and policymakers into a dialogue through which challenges identified at school level could be located within the existing policy framework, revealing more about how these policies are embedded within (or sit on top of) the local context.

A focus on positives rather than negatives (redressing the deficit discourse)

Much of the policy and research rhetoric around teachers over the past 20 years has presented a confusing picture. Teachers are held up as the builders of national development, but also its greatest threat. Angeline Barrett describes how teachers are seen as both the ‘causes and casualties’ of struggling education systems. The literature on teacher motivation has, rather ironically, focused almost entirely on teacher de-motivation. Our four studies eschew a focus on what is done badly and how can it be improved, in favour of what is done well and how can it be enhanced (and how these positive elements interact with and potentially influence other aspects of school life). For example, within the participatory video pilot, teachers had the opportunity to showcase what was important to them about their schools and their work. In the school effectiveness survey, the linked dataset enables the identification of ‘positive deviants’ – those teachers ‘adding more value’ to their students’ learning. Meanwhile, the study on head teachers’ professional networks sheds light upon the professional ties amongst the head teachers which can facilitate the process of personal and organisational learning.

Focus on impact – with a consideration around impact for whom

Findings emerging from the different research designs discussed within this blog can offer insights to shape policy which supports sustainability within education and more broadly. Whether by identifying gaps in the teacher planning and deployment process, by creating spaces for teachers’ voices in their own contexts, while also bringing them closer to policy through advocacy, or by exploring what it means to excel in the profession, how success is conceptualised and what this means for their students, understanding teacher experiences is a necessary first step for policymakers – and teachers – to effectively challenge and shape the existing structures they work within for the better. While such policy discussions will inevitably focus upon the ‘findings’ of research, working on a cross-institutional, cross-project, cross-paradigm symposium has allowed us to gain a greater understanding of the importance of the research design, and how the teacher is located within this. It is vital for research on teachers to contextualise findings within the approach used if it is to support teachers in a sustainable and sustaining manner.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks