By John Martin, Technical Director at Cambridge Education. This blog was originally posted on the UNICEF website on 12 July 2018.

© UNICEF/UNI110577/Noorani UNICEF supports this school in Rusizi District, Rwanda with teachers’ training, school supplies as well as construction of new child friendly classrooms, clean water supply and separate sanitation facilities for boys and girls.

Despite significant investments going into improving the performance of teachers, evidence suggests there is a crisis in both teaching and learning. Why have we (governments, development partners, stakeholders, ‘experts’) got it so wrong? And what could we change in the future?

Having worked on teacher programmes in developing countries for over two decades, I feel the need for significant shifts. I would argue that we:

- move from the narrow focus on teacher training to improving teacher performance

- attend to radically improving Initial Teacher Training (ITT), and

- create sustainable national models for genuine continuous professional development (CPD)

Let’s review these three areas in more detail.

1. By focusing strongly on teacher training over the past 20 years, we have distracted ourselves from the main goal of improving teacher performance

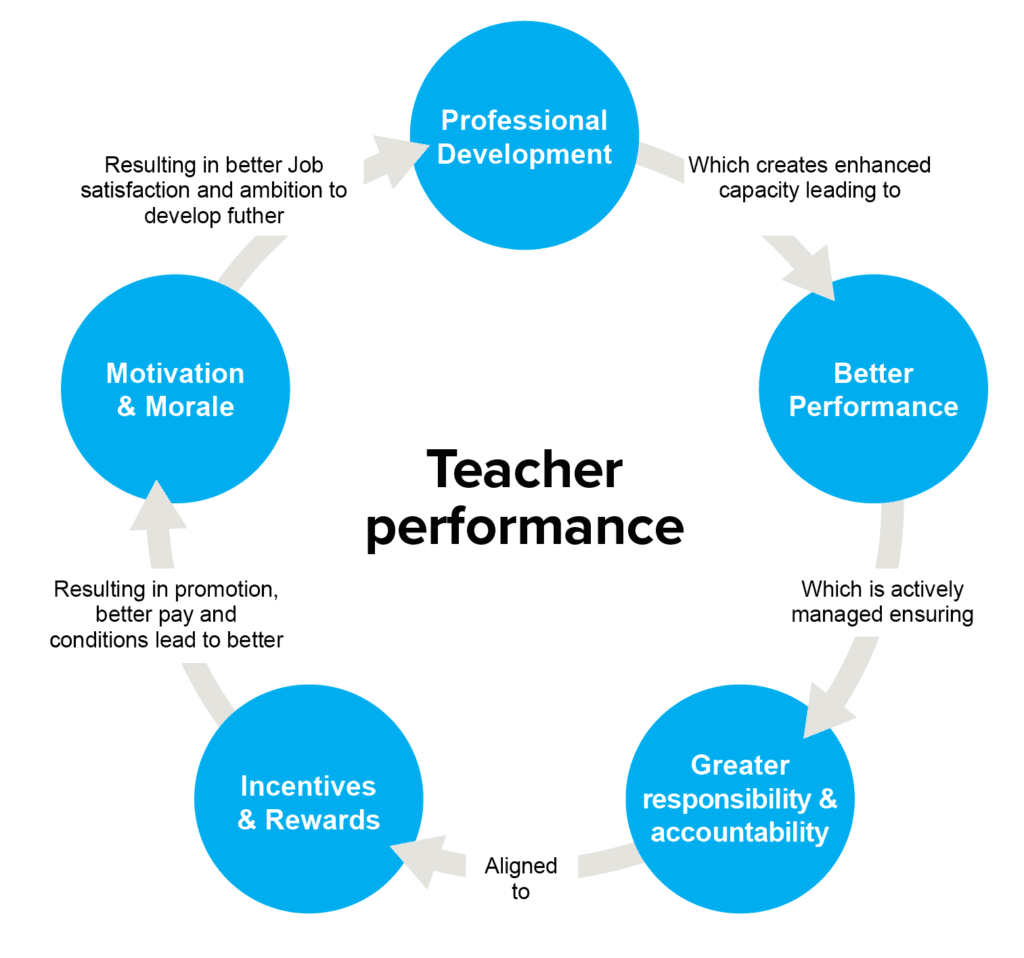

There is a tacit and longstanding assumption that if we want better teachers, all we need to do is give them more training. However, training is just one of a complex set of factors affecting the broader notion of performance. Other factors are: how motivated we are; whether we feel valued; how high our morale is; what roles we fulfil; whether our performance is aligned to the incentives we receive; and whether we are held to account for our performance.

The diagram below shows how all the factors of teacher performance relate to each other and form the basis for a cycle of continual improvement in teacher performance. Unfortunately, in many countries this cycle does not exist or is broken. The development of such a structure is not technically difficult but can only happen when political will exists and we need to be ready to leverage it when it does.

© Cambridge Education/2018/John Martin All factors of teacher performance relate to each other and form the basis for a cycle of continual improvement in teacher performance.

2. When working on teacher development, the focus has mainly been on training; ITT has been largely overlooked

Through ITT teachers can develop a foundation of skills and knowledge they can build on for the rest of their careers. Most ITT systems in sub-Saharan Africa are outdated and disconnected from the realities of the classrooms: they are long overdue for major systemic reform. Ghana and Nigeria are currently reforming their ITT systems by updating curricula, training tutors, increasing student time in classrooms, giving institutions more autonomy, increasing quality assurance and accountability, etc.

An alternative reform option is to innovate and look at completely different models of ITT. For example, college-based models of training where trainee teachers spend more than half their time in school with the support of a mentor. Or school-based models where schools recruit their own teachers and are responsible for their initial teacher training. This sort of innovation has not been tried in Eastern and Southern Africa and whilst reform of institutions of a radical kind always faces strong resistance, the potential for strengthening the quality and increasing the efficiency of ITT might be a game changer. More research, focused experimentation and investment in the area of ITT is required to guide such reforms.

© UNICEF/UNI82710/Pirozzi Sibonelo Khumalo, 13, stands at the chalkboard with his fifth-grade teacher at Lyndhurst Primary School in Estcourt, a town in KwaZulu-Natal Province. He is a participant in a UNICEF-organized child photography workshop.

3. Create sustainable national models for genuine continuous professional development (CPD)

CPD abounds in sub-Saharan Africa but it is largely remedial, and seeks to provide training that should have been given during initial teacher training.

Whilst one-off, in-service training — funded and delivered by development partners — has been a necessary short-term measure, the aim now should be to create affordable and sustainable systems for genuine continuous professional development.

One solution is to create an integrated teacher training system that combines both ITT and CPD. To be affordable, this would be based on much greater in-school training combined with outreach programmes from teacher training institutions. Such significant reforms would be best piloted on a small scale, both as proof of concept and as a chance to shift ingrained attitudes.

These three key arguments about teacher development show that if we want teachers who can perform better – as measured through improved learning of children – then we must address all of the various aspects affecting performance simultaneously.

Dive deeper into this topic:

Read the complete Think Piece on teacher performance (8 pages, 9 minute read)

Watch a summary presentation by the author (video, 23 mins)

John Martin is the Technical Director at Cambridge Education, and has 25 years’ experience designing and implementing large scale teacher performance and system strengthening programmes including in Nigeria, Ghana, Tanzania, DRC, China, South Africa, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Uzbekistan, Turkey and currently in Uganda.