This blog was written by Elizabeth Tofaris, University of Cambridge, on behalf of the the Impact Initiative for international development research. The Impact Initiative seeks to connect policymakers and practitioners with the world-class social science research supported by the ESRC-DFID Strategic Partnership, maximising the uptake and impact of research from: (i) the Joint Fund for Poverty Alleviation Research, and (ii) the Raising Learning Outcomes in Education Systems Programme.

Many developing countries have made good progress in improving enrolment rates since universal primary education became a UN global target over 15 years ago. But for countries in Africa, such as Lesotho and Malawi, which are deeply affected by the HIV/AIDS crisis, these gains mask a troubling picture of low levels of achievement and worrisome drop-out rates. For orphaned or vulnerable children who struggle to attend class, for example because they care for chronically ill parents or work to support themselves and their families’ income, the problem is made worse by school policies which actively discriminate against poor households.

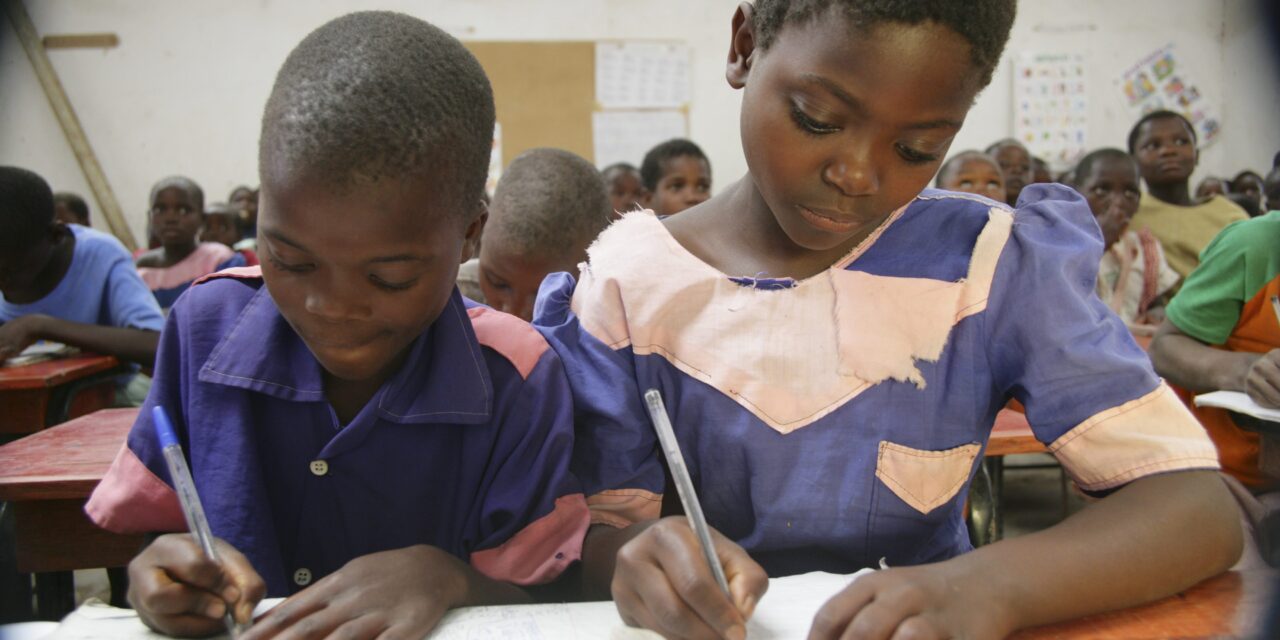

©-Giacomo-Pirozzi-Panos-Pictures.

Children studying in class. Primary education is free of charge in Malawi. However, although many children start school, around 60% drop out before completing their primary schooling.

Strengthening Open and Flexible Learning

Pioneering techniques including ‘School in a bag’, buddy systems and catch-up clubs have been used by researchers from University College London’s Institute of Education and their Southern African partners to help ensure that disadvantaged children, particularly those affected by HIV/AIDS, stay in school in Malawi and Lesotho.

The research team wanted to study whether a flexible approach to learning could improve educational achievement and reduce the risk of dropout for vulnerable children. Key components of their ground-breaking SOFIE model (Strengthening Open and Flexible Learning for Increased Educational Access in High HIV Prevalence Countries), included a ‘school in a bag’ that held pens, notebooks, textbooks and self-study guides for English and Maths, designed to encourage independent learning for children for whom school attendance was often erratic; a buddy system, providing peer-support for learning; and catch-up clubs, run by youth volunteers providing additional learning opportunities in friendly, informal environments, and which were arranged after school hours.

Between April 2007 and July 2010, the team developed and piloted these distance- and flexible-learning techniques in 20 primary schools in Malawi and 16 secondary schools in Lesotho, all of which were located in areas where HIV/AIDS was highly prevalent and where school drop-out rates were high. In both countries, the schools saw reduced drop-out rates (up to 45 per cent in Malawi), particularly for older children.

Drop-out rates reduced

In both countries, school drop-out rates reduced and Maths scores improved. In fact, the positive effects spilled over to a much wider group thanks to improved teacher engagement and changes in exclusionary practices. Children’s confidence and self-esteem increased, and the buddy system helped reduce isolation and discrimination, build friendships, and increase motivation to continue with school.

Particular success was attributed to the innovative self-study guides and, critically, the collaborative nature of the project – community members, teachers and youth volunteers were all included in helping to improve the inclusiveness of schools by developing ‘circles of support’ around vulnerable children at risk of dropping out of school. It was clear that against a context of underlying poverty and disadvantage, having someone to provide emotional support, take an interest and pay attention to whether they are in school or not (be it a buddy, teacher or community leader), was of great value to pupils who regularly experienced isolation.

Raising the profile of open and flexible learning techniques

In Lesotho, a formal qualification for teachers on guidance and counselling has been initiated. And in Malawi, pilot schools put in place plans to change discriminatory school policy, improve their inclusiveness, and support disadvantaged children. Templates of the self-study guides were shared with district education offices and project outcomes informed the design of non-governmental ‘bridging’ programmes and clubs to provide learning support for senior primary girls during the transition to secondary education and to reduce the risk of dropout. Several of the youth volunteers involved in the project have since been accepted onto a national distance-learning teacher training programme.

The project, ‘Strengthening ODFL systems to increase education access and attainment for young people in high HIV prevalence SADC countries’ was funded by ESRC-DFID’s Joint Fund for Poverty Alleviation Research. It was led by Principal Investigator Professor Pat Pridmore and Chris Yates, University College London’s Institute of Education; team statistician Matthew Jukes, Harvard University; Ephraim Mhlanga, South African Institute for Distance Education; in collaboration with in-country researchers, including Catherine Jere, the University of Malawi and the National University of Lesotho. See also: http://sofie.ioe.ac.uk/

References

Jukes, M.C.; Jere, C.M. and Pridmore, P. (2014). ‘Evaluating the Provision of Flexible Learning for Children at Risk of Primary School Dropout in Malawi’, International Journal of Educational Development 39: 181–92

Jere, C.M. (2012). ‘Improving Educational Access of Vulnerable Children in High HIV Prevalence Communities of Malawi: The Potential of Open and Flexible Learning Strategies’, International Journal of Educational Development 32.6: 756–63.

Pridmore, P. and Jere, C.M. (2011). ‘Disrupting Patterns of Educational Inequality and Disadvantage in Malawi’, Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 41.4: 513–31.

Pridmore, P. (2010). End of Award Report: Strengthening ODFL Systems to Increase Education Access and Attainment for Young People in High HIV Prevalence SADC Countries, Swindon: ESRC.

Well this is a good approach though it has negative impacts on the social inclusion aspects. To me it breeds isolation of the learners and compromises the pleasure of learning how to interact with fellow learners in a classroom scenario which in itself promotes social development.

Thanks for the great initiative as students are confronted with a myriad of challenges to overcome before they can effectively partake in the learning process. Mother groups and community learning centers run by volunteers really assist in providing social-psychological support and academic catch-up to the venerable learners. Low quality of education environment for curriculum implementation has been our challenge also for some time now. Provision of equal learning opportunity and enhancement of learning outcomes has been always a sought after agenda by MoEST agents but has proved very challenging to attain.

But I wanted to learn from your project some of the discriminatory policies that schools practice especially in Malawi so that we can bring to attention of fellow policy makers and act accordingly.

Once again, thanks for the great initiative.

Hi Thabitha, we hope that using these models actually reduces isolation. The rationale behind this project was to integrate more flexible learning systems into existing school systems and we worked directly with ordinary, formal primary schools. These children were still attending class when they could, were not always able to attend regularly – so rather than ignoring them, letting them fall behind in their lessons and allowing exclusion to deepen, schools and youth volunteers provided additional support. And by linking these identified learners with school ‘buddies’ (peer mentors), we found – encouragingly – that this build friendships between learners, strengthened social networks and, according to qualitative data, reduced isolation and discrimination.

I heavily support the unconventional means of teaching, which I, personally, call deliberate initiatives towards specific situations in a specific learning context. For example, Mponela CDSS has copied from Dowa Secondary school by having additional 13 also blackboards outside the class room, on the walls of the fences. I have also observed the same scenario at Chimutu CDSS on the area 18 roundabout to Bingu National Stadium in Lilongwe, Malawi. In all the schools I have keenly observed a good number of students coming back to school after knocking off to help each other solve maths problems guided by a fast learner(a buddy). This has, to a great extent, reduced isolation and likely increased concentration of students on their school work. Some teachers like me, have an extra time to copy summaries for English and Chichewa which I teach and offer home work which has increased my teaching three fold in a day. To an extent, has made teaching and learning a shared activity. Students negotiate the answers as a group which likely enhances self confidence, self esteem, independence, and initiative at adjusting to learning problems. To an e extent, it has promoted study time to those who operate in CDSS. I believe these are key factors to learning of every student no matter where that student is. What is remaining is for government to tap these initiatives from isolated schools and initiate them for adoption in other schools, nationally. A bottom- top sort of approach which can be proposed to donors and stakeholders to support on the ground. However, the problem lies with bureaucratic approach in most developing countries which is not flexible enough to learn from field officers experiences. This is compounded by our universities which promote creativity which tend to be Eurocentric and impressive to the donor agencies.

It is not unconventional; it is flexible learning. Too many times negative words are used for positive things. In Australia there are several ways of learning flexibly. There is home-schooling where the children are taught by their parents instead of attending regular school. In some country areas and outback stations children learn at home via a digital link-up with the teacher in a far away city. I finally was able to finish the last year of high school because I studied via the postal service, receiving my study guides and lessons in hard copy. The lessons were sent in bulk so that I could plan my study over several weeks and be in charge of my own learning. There is nothing unconventional about this, nor the Malawi and Lesotho methods; these are flexible learning experiences and all valid. However, the problem in Australia is with the bureaucratic and Eurocentric approach (thank you Johnnie Kasonda) to Indigenous people/s and their struggle for bilingual education using Indigenous learning methods. This is an ongoing process.