This blog was written by Freda Wolfenden, Professor of Education and International Development at the Open University, and Chair of the Executive Committee for UKFIET. It was first published on the Education Commission website on 30 July 2018.

This blog was written by Freda Wolfenden, Professor of Education and International Development at the Open University, and Chair of the Executive Committee for UKFIET. It was first published on the Education Commission website on 30 July 2018.

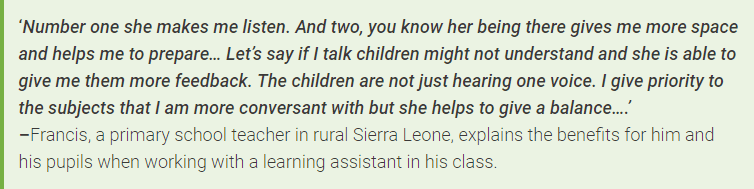

Learning assistants are young women participating in a community-based pathway to become qualified teachers. Listening to Francis and observing how the learning assistant adeptly undertook a range of tasks – rearranging children so that everyone could see, taking attendance, and distributing materials – I was reminded of the isolation, complexity, and demands of the teaching role. Too rarely do we engage in creative, holistic thinking about how educator roles could be redesigned to take into account evolving conceptions of professional practice as well as what is involved in learning the practice in today’s schools.

A recent research assignment for the Education Commission’s Education Workforce Initiative(EWI) was an exceptional opportunity for our team at the Open University to explore such new thinking. Our brief was to understand the opportunities and challenges for education workforce redesign and identify promising education workforce innovations from across the world. However, finding such innovations proved to be much more difficult than anyone anticipated. We scoured numerous databases, but almost all the examples were small-scale, highly experimental, and had yet to be fully evaluated – particularly against financial criteria. Outside high-income contexts, there is an absence of system-level workforce redesign and no parallel to the redesign that has taken place in the global health workforce, which has helped create well-established roles to support medical professionals.

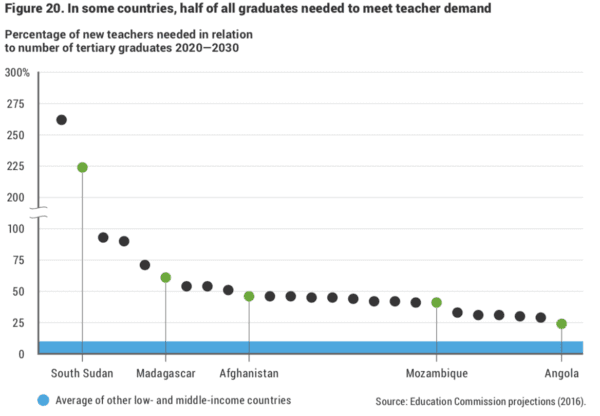

Ideas about school classrooms have remained remarkably consistent and pervasive over time and geographical space: the teacher working relatively autonomously in an enclosed space with a group of students. Perhaps the ubiquitousness of such models reinforces their continued legitimacy and efficacy? But, for us, the need to challenge this entrenched model of the school classroom is crucial when population, education systems, and budget projections are taken into account. Merely expanding current systems will not be adequate to meet increasing demand. In some Sub-Saharan African countries, for example, more than half of all graduates would need to become teachers to fulfill demand.

Eventually, we were able to highlight a number of interventions involving modified or new workforce roles in different contexts. Unsurprisingly, almost all of these exploit the increasing availability and affordability of digital technologies – particularly mobiles and visual media, either directly with students or to support professional learning and development of teachers. One particularly powerful set of examples involves students interacting remotely with specialist teachers (or other experts). Use of this approach to teach science in far-flung secondary schools in the Amazon has been much discussed in previous reports, but there is also sustained use on other continents such as Ghana, (MGCubed) and Bangladesh (JAAGO). Initial evaluations of such schemes are promising, and there is exciting potential to combine them with independent or peer-supported study of materials (as in a flipped classroom approach) and with online interactive science laboratories to enrich students’ learning experiences.

Other potentially interesting innovations involve harnessing support for learning from beyond the immediate education community, responding to local needs with local resources. For example, we have seen business leaders mentoring school leaders in South Africa, community volunteers supporting school readiness in Tanzania, and female high school graduates acting as role models for students in lower secondary school classes.

Synthesising learning from across these initiatives, we are struck that many conceptualise teaching as a collective endeavour undertaken by teachers and other practitioners collaborating in teams and that digital technologies provide tools which are mediated and leveraged by good teaching but do not replace teachers. Of course, in many systems support roles already exist and are taken for granted, which is perhaps why there is so little analysis of them. But perhaps there is a case for configuring these roles to more effectively meet the demands of contemporary education goals and utilise new ideas on the collective nature of professional practice and the availability of technological tools.

Enacting large-scale workforce redesign will require an in-depth understanding of what is happening now to identify the leverage points and potential barriers in any context. But robust data on what teachers, school leaders, and district officials actually do and the details of their working relationships with other professionals is remarkably scant. Hence a key part of the next stage of the EWI research will be an empirical look at the roles associated with schools in the EWI focus countries. We will examine not only the vision for these roles in the system but also how these roles – teachers, school leaders, district officials, and teaching support staff – are enacted and experienced. Equipped with this analysis, policymakers, educators, and their communities can begin to visualise new ways of organising learning appropriate to the context. This is critical if teachers are to have space to develop the technical sophistication and wisdom required to be effective and ensure every child has the opportunity to learn the skills and knowledge they need to live a fulfilled, healthy, and productive life.

Learn more about the Education Commission’s Education Workforce Initiative, and read our initial literature review.

Freda Wolfenden is a Professor of Education and International Development at The Open University UK.