This blog was written by Kerry Taylor-Leech, senior lecturer in second language teaching and curriculum literacies at Griffith University, Queensland; and Sue Ollerhead, lecturer in language education at Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. It was originally posted on the IIEP Learning Portal on 6th November 2019.

Multilingualism is good for us. Not only does speaking more than one language keep our brains healthy as we age, but it has multiple benefits for children too, such as giving them an academic advantage and improving their employment prospects once they leave school. Moreover, multilingualism gives us access to more than one culture, and improves our understanding of our own cultures.

But what does this mean for classroom teaching, especially in school contexts that equate English language proficiency with academic success? How can teachers harness the benefits of their students’ multilingualism, while simultaneously helping them to develop the academic language they need to succeed?

A team of Australia-based educational researchers has embraced this challenge by working with the British Council to produce a ground-breaking collection of multilingual classroom activities. These activities are aimed at teachers who work with English as a subject or use English as the medium of instruction in low-resource, multilingual classrooms. The team comprised researchers from the University of South Australia, Griffith and Macquarie Universities, all of whom have extensive experience of teaching in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts, including sub-Saharan Africa, northern Africa and southeast Asia. Two team members explain what lies behind the publication.

A team of Australia-based educational researchers has embraced this challenge by working with the British Council to produce a ground-breaking collection of multilingual classroom activities. These activities are aimed at teachers who work with English as a subject or use English as the medium of instruction in low-resource, multilingual classrooms. The team comprised researchers from the University of South Australia, Griffith and Macquarie Universities, all of whom have extensive experience of teaching in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts, including sub-Saharan Africa, northern Africa and southeast Asia. Two team members explain what lies behind the publication.

For many years, teachers of English have been told that using students’ home languages in English lessons should be avoided at all costs

A growing body of research literature shows that drawing on students’ home language and cultural backgrounds in classroom teaching validates their identities and provides a strong foundation for additional language learning. Yet the reality for many multilingual students, especially English language learners, has been that their home languages are left at the classroom door or regarded as an obstacle to the development of the language of schooling and learning in general. For many years, teachers of English have been told that using students’ home languages in English lessons should be avoided at all costs.

Language as a resource

Multilingual classrooms are a growing phenomenon around the world, as a result of rapid increases in global mobility and migration. Within these classrooms, students may have different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, may speak one language at home and another language at school, or be learning the language of instruction as an additional language. International agencies such as UNICEF, UNESCO and the European Commission contend that multilingual education can play a significant role in engaging diverse learners. As well as supporting academic success, classrooms that promote multilingualism can foster positive identities associated with their home cultures. This position is supported by Richard Ruiz’s notion of “language as a resource” (1984) which advocates for the use of students’ home languages as resources for learning and teaching. In practice, a language-as-resource perspective implies that teachers should use students’ home languages as a tool for thinking and communication while simultaneously learning and developing proficiency in the language of instruction. Nevertheless, English still overwhelmingly dominates lessons in many classrooms throughout the world where students read, write, listen and speak only in English. Despite considerable research pointing to the importance and benefits of incorporating multilingual pedagogies into classroom practice, there are few materials available to educators that explain how this can be done deliberately and systematically in lesson planning and lesson delivery.

Signs of change

Happily, in recent years, publications, conferences and professional development materials have advanced thinking about the medium of instruction and ways to approach teaching that challenge the “national/official language-only” view.

Using multilingual approaches: Moving from theory to practice

A new British Council publication, Using multilingual approaches: Moving from theory to practice, reflects the growing body of research evidence showing that preventing learners from using their home languages in the English language classroom not only impedes learning and denies their linguistic human rights, but also loses valuable opportunities for teachers to draw on their students’ knowledge and experience as resources for teaching. This collection of activities was developed in response to the British Council’s conscious decision to promote multilingual approaches to teaching English internationally. The activities are designed to acknowledge learners’ home languages and cultures when teaching English as an additional or foreign language, or using English as the medium of instruction in multilingual classrooms. The activities are grounded in research-based pedagogic principles, briefly outlined below.

Funds of knowledge in the language classroom

It has long been recognised that one of the key characteristics of high-quality teaching is the ability of teachers to engage students’ prior understandings and experiences and background knowledge. This prior knowledge is encoded in their home languages, and therefore it is vital that teachers facilitate the transfer of both concepts and skills from students’ home languages to English.

This view of language is complemented by Luis Moll’s notion of ‘funds of knowledge’ (1992), which refers to the rich bodies of cultural knowledge that exist within students’ households and communities. Moll argues that when teachers tap into this type of knowledge by building relationships with their students and their wider social networks, they allow for meaningful learning opportunities. Teaching practices that tap into multilingual ways of reading, writing and speaking allow students to access the cultural resources that enhance the personal significance of their classroom work, as well as expanding access to knowledge through texts in more than one language.

Purposeful translanguaging

One of the most successful approaches to bilingual teaching and learning has been the purposeful and simultaneous use of two languages in the same classroom, a process that is referred to as translanguaging. The activities in this collection break new ground in being designed to enable teachers to constantly draw on and make use of students’ emergent bilingual skills. The activities are designed in a planned and purposeful way to encourage students draw on the most appropriate linguistic resources they have, allowing teachers to design intercultural and inclusive lessons that support English language learning but also draw on learners first languages and their community and family funds of knowledge.

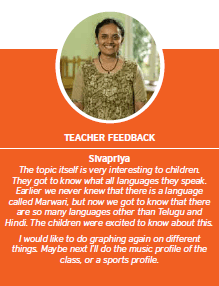

The activities were workshopped with and piloted by teachers in India, who applied them to their own classrooms and provided rich feedback and valuable ideas. This short film explains more about the process and rationale behind the resource.

valuable ideas. This short film explains more about the process and rationale behind the resource.

Project leader, Associate Professor Kathleen Heugh sums up the social significance of the project in her observation that: “Forbidding a child to use his/her language is a violation of their rights, and deeply problematic for their future. We cannot afford to have students marginalized, feeling lost and falling out of the school system. Using students’ home languages, bringing in their own knowledge systems to the classroom should be the most important aspect of any school language policy”.

References

Luis C. Moll, Cathy Amanti, Deborah Neff and Norma Gonzalez (1992) Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms, Theory Into Practice, 31:2, 132-141.

Richard Ruíz (1984) Orientations in Language Planning, NABE Journal, 8:2, 15-34.

Awesome article, strike to the point, thanks for sharing