This blog was written by Kevin Watkins, Chief Executive of Save the Children UK, as the organisation celebrates its 100 years and launches the Stop the War on Children campaign. It was originally posted on the Project Syndicate website on 14 May 2019.

Around 420 million children are currently living in conflict-affected countries – more than at any time in the last 20 years. Many are deliberately targeted by armed combatants for heinous crimes, including killing, rape, and kidnapping.

THE HAGUE – Over a century after its construction, the Peace Palace in The Hague – home to the International Court of Justice, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague Academy of International Law, and the Peace Palace Library – stands as a monument to the soaring ambition and dashed hopes of a bygone generation. But it is also a monument to a vision that the world needs more than ever.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, The Hague hosted the first international conferences aimed at establishing shared norms governing conflict. The conventions that emerged from the 1899 and 1907 events formed the first multilateral treaties addressing the conduct of warfare, including the protection of civilians.

But the ambition went even further. The Peace Palace was built to host the Permanent Court of Arbitration, a body mandated to resolve territorial disputes in a courtroom, rather than on a battlefield. Andrew Carnegie, the American steel magnate who financed the Palace’s construction, predicted at the opening ceremony in 1913 that the end of war was “as certain to come, and come soon, as day follows night.” Tragically, within a year Europe descended into the Great War.

But there is a chance to renew the promise that the Peace Palace once represented. Later this week, in that very building, Save the Children will mark our centenary with the launch of our Stop the War on Children campaign, a global call for action to protect children threatened by war.

But there is a chance to renew the promise that the Peace Palace once represented. Later this week, in that very building, Save the Children will mark our centenary with the launch of our Stop the War on Children campaign, a global call for action to protect children threatened by war.

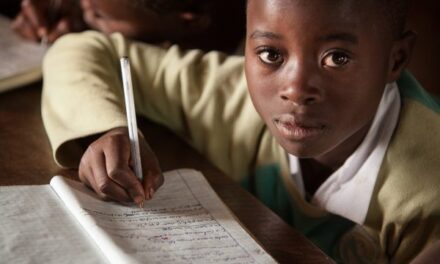

The campaign goes to the very heart of Save the Children’s mission. Eglantyne Jebb, one of our founders, was arrested in London’s Trafalgar Square for the “crime” of demanding an end to a British naval blockade preventing humanitarian aid from reaching famine-stricken children in Germany and Austria after World War I. She went on to build a movement aimed at protecting children from armed conflict. “All wars, just or unjust, disastrous or victorious,” she wrote, “are waged against the child.”

Jebb would surely be shocked by the systematic violence perpetrated against children in today’s wars. Around 420 million children are currently living in conflict-affected countries – more than at any time in the last 20 years. Many are deliberately targeted by armed combatants for heinous crimes, including killing, rape, and kidnapping. The United Nations documented over 25,000 grave violations against children in 2017, the highest number on record.

Many more children are treated as “collateral damage” by armed combatants who fail to undertake even the most rudimentary precautions to protect civilians. Last August, Saudi-led forces in Yemen dropped a bomb on a school bus, killing 40 children. In Syria, schools and hospitals are among the targets of government and Russian forces in the rebel-held Idlib province. The indiscriminate use of high explosive weapons in densely populated urban areas poses a threat to civilians in general, and to children in particular. As Save the Children documents in a new report, three-quarters of the 7,364 recorded deaths suffered by children in the world’s five deadliest conflicts in 2017 – Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria, Nigeria, and Iraq – were the result of blast injury.

Then there are the hundreds of thousands of child deaths caused by malnutrition, the collapse of vital health services, and humanitarian blockades designed to obstruct vital aid. Hunger and disease have already claimed over 85,000 lives in Yemen.

The scale, magnitude, and intensity of this war on children demands much more than handwringing and heartfelt expressions of concern. Attacks on children are attacks on our shared humanity, and on the universal rights and values that underpin the multilateral order. There must be an effective response.

The first line of defence is the international rule of law. Instruments such as the Geneva Conventions, the International Criminal Court, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child represent an impressive defence arsenal. But without compliance, these are weapons with all the teeth of a paper tiger.

Law is a powerful force for protection, but only when it is enforced – and there is no enforcement of the rights protecting children in war. We know the names of some of those responsible for possible war crimes carried out by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, by the Assad regime in Syria, and the Myanmar military’s attacks on the Rohingya, which could qualify as genocide. But it is unlikely any of the perpetrators of these and other crimes against children lose sleep worrying about a looming day in court.

Double standards and inconsistency inevitably weaken the rule of law. For example, while the British government deserves great credit for brokering a ceasefire in Yemen, it issues export licenses to BAE Systems, a company arming the perpetrators of possible war crimes in Saudi Arabia. Allowing commercial interests to trump the defense of human rights in Yemen inevitably weakens the UK’s role as a global champion of universal rights.

We need to end the impunity of those who fail to act on their responsibility to protect children in war zones. That means rethinking a legal and human-rights architecture that lacks the power to investigate, prosecute, and deliver justice to the victims. It also means adapting established laws to emerging evidence. New research shows unequivocally that children are far more likely than adults to be killed and maimed by blast injuries. The onus is now on armed actors to act on this evidence as they assess civilian risk, and on national and international judicial authorities to consider the child-specific effects of blast injuries when investigating possible violations of humanitarian law.

The drive to increase accountability must be accompanied by support for children who have been traumatized by the injuries they have sustained, or the experiences of loss, terror, and displacement they have suffered. These invisible wounds of war cut deep, undermining recovery. Aid donors could start by placing psycho-social support at the heart of post-conflict reconstruction. Launching the Stop the War on Children campaign at the Peace Palace, a century-old symbol of a failed mission, may seem like the prelude to a lost cause. But at a time when the world is so deeply divided, it is worth tapping into the ambition behind that mission, the faith in human solidarity that underpinned it. Children are our future. If we fail them, we will fail ourselves.