By Gauthier Marchais and Sweta Gupta from the Institute of Development Studies, and Cyril Brandt from the Institute of Development Policy, University of Antwerp. These issues were discussed during a session at the September 2019 UKFIET conference on inclusive education systems.

Does it help to have a relative who is a public official, or a military actor? Do different types of kinship networks change the impact of violent conflict on households and students? How do extended families cope with school fees in contexts of violent conflict?

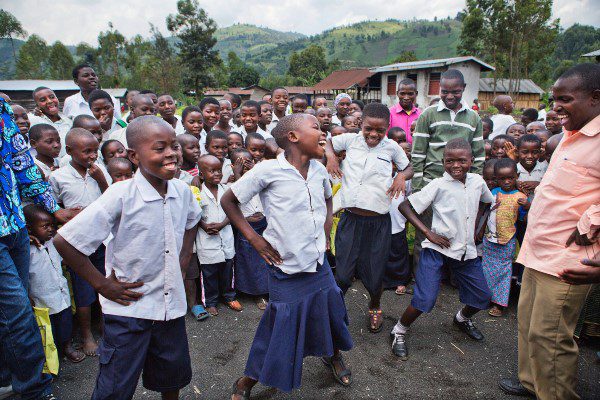

This ongoing study offers a multi-dimensional analysis to explore these questions. It analyses how social relationships mediate and influence marginalisation from education in contexts of violent conflict. The study is a component of an education project aiming to increase young girls’ access to school in six provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, entitled REALISE (Réussite et Epanouissement via l’Apprentissage et L’Insertion au Système Educatif), funded by DFID and implemented by Save the Children. The research component of the project is led by the Institute of Development Studies.

Focus of the study

The study seeks to further the understanding of the factors that enhance, or mitigate, marginalisation from education in contexts of protracted violent conflict. Specifically, it analyses the role of social networks and relationships – both inherited and constructed – in mediating the effects of violent conflict on education. Conflict studies have analysed the reconfiguration of social networks in armed conflicts and protracted crises, but this research has thus far – to our knowledge – not been taken up by educational researchers, which provides the starting point of this project. The study uses a mixed-methods approach, combining a quantitative study based on data collected through a survey, and a qualitative analysis based on interviews carried out in the province of Tanganyika over a period of three months.

The study partially focuses on the Batwa people – often referred to as Pygmies – in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC, province of Tanganyika). The have suffered longstanding marginalisation from social, economic and political life in the province, as well as from education. Since the early 2010s, a violent conflict between Batwa and Bantu populations has caused a humanitarian crisis that went largely unnoticed by (inter-)national media, and has significantly worsened the marginalisation of Batwa populations, with complex effects on their social and economic positioning. Our research explores how longstanding forms of marginalisation from education can be accentuated by violent conflict, but also how new forms of marginalisation emerge as a result of violent conflict. By doing so, we seek to further the understanding of education provision in contexts of protracted violence, with a specific focus on the DRC, where the resilience and surprising expansion of the poorly funded Congolese education system has left important segments of the population behind.

Results

Our preliminary results provide evidence of the social and economic marginalisation of the Batwa, as well as their marginalisation from education. Batwa children are more likely to have never attended school, and very few Batwa complete the full six years of primary school. Batwa children exhibit worse socio-emotional well-being outcomes, are more likely to be depressed and to exhibit behavioural problems, and less likely to exhibit pro-social behaviour. The qualitative component of the study shows evidence of persistent discrimination of Batwa students in schools. Moreover, we find that, during the Batwa-Bantu conflict, Batwa households have been more exposed to violence than non-Batwa households. While the analysis is still under way, tentative results show that social networks play a role in marginalisation from education: preliminary results suggest that knowing someone in a position of authority, and having family support networks increases the chances of being enrolled in a school. Batwa households score very low in both categories, which suggests that their social marginalisation increases their marginalisation from education.

Limitations

The study has faced constraints, such as a general lack of knowledge on IDPs, limited existing research on the relationships between armed conflict and education in the DRC, on-going armed conflict in the province of Tanganyika, and Ebola crisis in eastern DRC.