This blog was written by Alice Castillejo, Program Advisor with Translators without Borders. Alice will be making a presentation entitled ‘Overcoming educational inequality in emergencies through language’ at the September 2019 UKFIET conference on inclusive education systems.

Humanitarians don’t routinely collect and share data on what languages people speak. Translators without Borders (TWB) has found this in emergencies across three continents. In northeast Nigeria, for instance, this means that the humanitarian response relies largely on Hausa to communicate in an area with over 30 languages. As a result, anyone who has had less access to education (including children themselves) will have less opportunity to get information or make complaints.

Humanitarians don’t routinely collect and share data on what languages people speak. Translators without Borders (TWB) has found this in emergencies across three continents. In northeast Nigeria, for instance, this means that the humanitarian response relies largely on Hausa to communicate in an area with over 30 languages. As a result, anyone who has had less access to education (including children themselves) will have less opportunity to get information or make complaints.

Humanitarian organisations assume that national staff have the necessary information on local languages. They often will, at least in part. However, we should recognise that they are likely to be more educated, and are often men from majority language groups. This means that they may be less aware of the languages less educated or more marginalized groups speak.

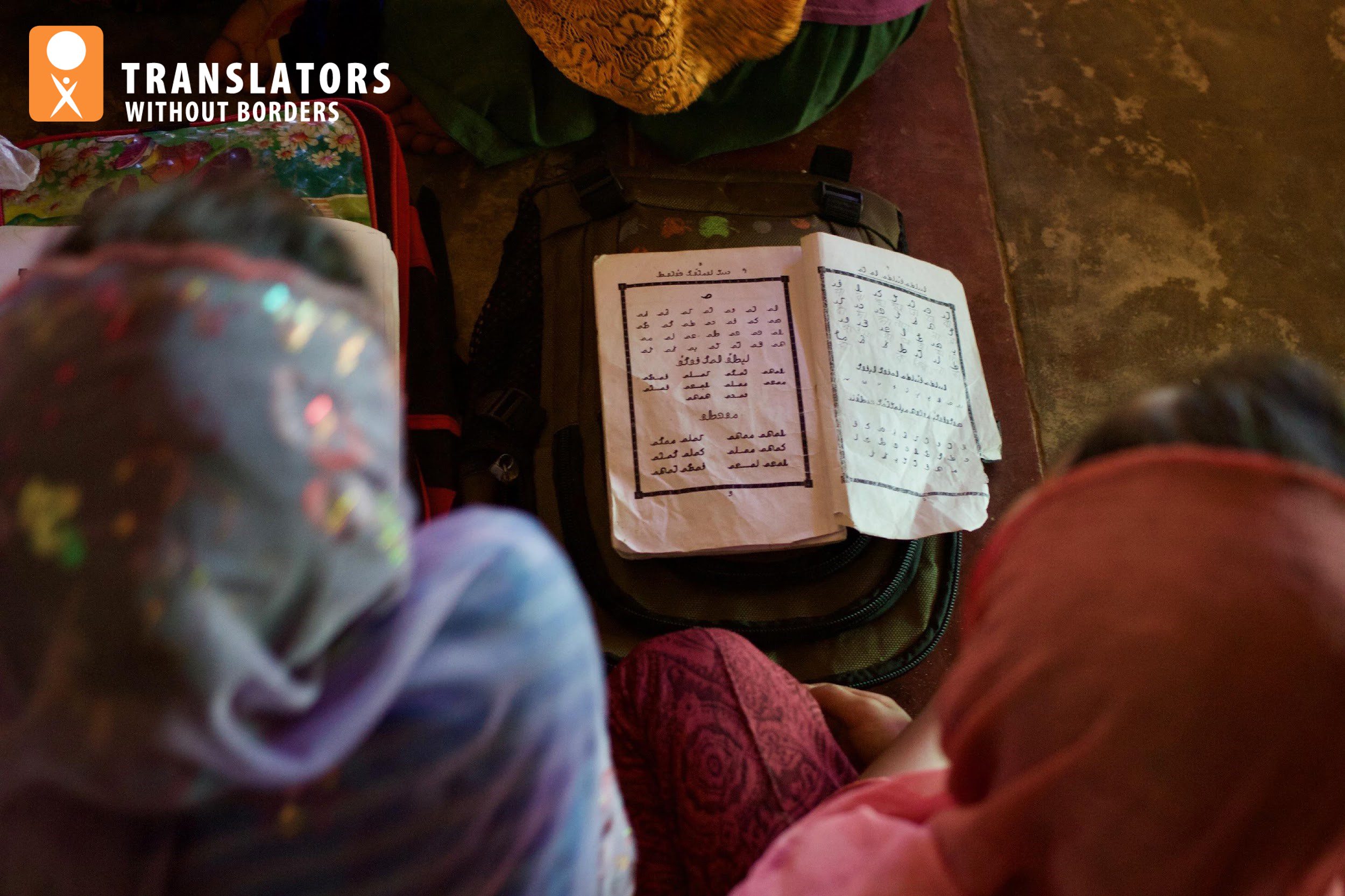

We should also remember that national staff need their jobs. In the Rohingya response in Bangladesh, organisations hire speakers of the local language of Cox’s Bazar, Chittagonian, on the basis that it is close to Rohingya. Yet not close enough: many words and expressions in one language are not readily understood by speakers of the other. Chittagonian staff regularly report that they can be fully understood by the Rohingya community they serve. TWB’s comprehension testing found that in fact 36% of Rohingya people surveyed could not understand a simple sentence in Chittagonian. It takes training and support such as TWB provides to help Chittagonian field workers navigate the language barriers effectively.

To compound the data challenge, humanitarian organisations often don’t support enumerators to gather information across languages. Enumerators have to make on-the-spot translations from the written survey to the many minority languages they might encounter. They then translate the information back into the survey language to complete the form. This presents a multi-layered problem:

- Enumerators don’t understand the source text. (In a TWB study in northeast Nigeria, teams of enumerators could understand at best 80% and at worst just 10% of the terms in their surveys.)

- Enumerators struggle to match complex answers in another language with drop-down answers in the survey language. Collaboration between TWB and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) on translating recorded interviews from northeast Nigeria confirmed this. It found that when enumerators struggled to understand answers from the menu, they chose the one they understood best or agreed with. Respondents views were lost in the process. Even an explanation to ensure informed consent was mistranslated or skipped on occasion.

Unless we support enumerators better on language, or use recording and translation for quality assurance, we will never know if we are capturing the views and needs of minority language speakers.

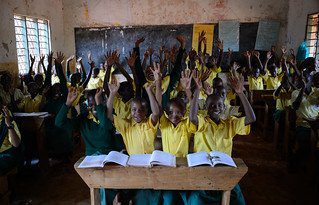

So what does this mean for education?

The refugee response in Cox’s Bazar highlights what can happen in the absence of reliable data on language:

- You can assess children’s competence using languages they don’t speak. That means you haven’t really assessed their competence at all.

- You can train teachers using languages they don’t fully understand, meaning that they struggle to understand recommended practices.

- You can hold parent meetings in a language they are not confident in, leaving them still unclear about important aspects of their children’s education.

Nigeria illustrates another common consequence of a lack of data. As in many contexts, the school system cannot track how speakers of marginalized languages progress through education. If language is not tracked as a factor of exclusion like gender or disability, we won’t know when some groups are left behind.

There are solutions to all these issues. Some require investment, some human capacity, some political will. Education organisations can call on TWB’s expertise to address language barriers to education. But the starting point is the easiest and cheapest: to gather and share language data and use it as a key indicator of educational inclusion.