This blog was written by Ana Carolina Rodrigues-Vasse. Ana works at the University of Groningen where she teaches, researches and contributes with external projects on international development, agriculture and popular education in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. For the 2019 UKFIET conference, 17 individuals, including Ana, were provided with bursaries to assist them to participate and present at the conference. The researchers were asked to write a short piece about their research or experience.

The theme of the 2019’s UKFIET conference ‘Inclusive Education Systems: Future, Fallacies and Finance’ brought to the table discussions that have echoed among institutions and practitioners recently. Looking from the perspective of middle- and low-income countries, challenges remain numerous to approaching inclusion from a democratic and truly diverse point of view. Public policies in education are increasingly contested nowadays, when political polarisation dominates the public agenda. In this general context, thinking theoretically and practically of education as a human right (in line with the right to education framework), as well as an instrument to encourage critical thinking and skills development in a changing world, is a milestone.

The case of education in conflict and post-conflict situations accounts for an even higher politicisation. In fact, as Kelsey Shanks argued, in deeply divided societies, education might contribute to reinforce identities by stressing differences between communities, thus creating loci for contradictions and disputes between national policies and local practices in education. Further than that, as some presenters in this conference sought to highlight – Prof. Mario Novelli is among those – international political economy also influences on how education becomes a part of the political game of ‘helping’, therefore being particularly strategic for mainstream developmental agencies involved in North-South cooperation.

The case of education in conflict and post-conflict situations accounts for an even higher politicisation. In fact, as Kelsey Shanks argued, in deeply divided societies, education might contribute to reinforce identities by stressing differences between communities, thus creating loci for contradictions and disputes between national policies and local practices in education. Further than that, as some presenters in this conference sought to highlight – Prof. Mario Novelli is among those – international political economy also influences on how education becomes a part of the political game of ‘helping’, therefore being particularly strategic for mainstream developmental agencies involved in North-South cooperation.

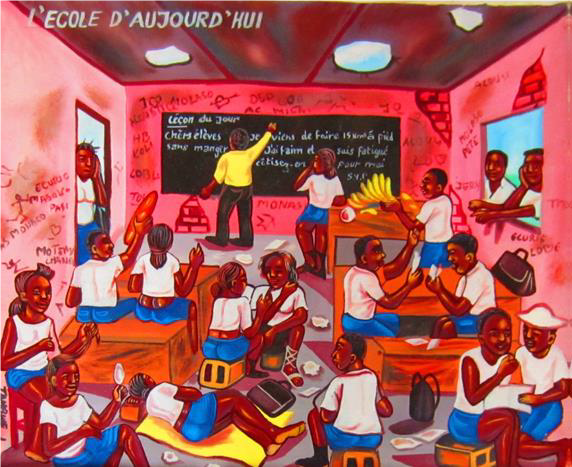

Bearing these thoughts in mind, we could draw some reflections about the contribution that my colleague Josje van der Linden and I brought to the conference concerning ‘Youth in (post-)conflict areas’. Our empirical case was a summer school in Gulu, northern Uganda, which we co-organised together with other partners. Departing from existing institutional cooperation between Gulu University and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and following the establishment of the UNESCO Chair on ‘Lifelong Learning, Youth and Work’ based in Gulu itself, the summer school programme aimed at opening a conversational space among national and international participants and the local communities.

Theoretically inspired by participatory action research (PAR), we understood international cooperation as an opportunity to promote a ‘joint production of knowledge’. Besides, we understood our roles in it as facilitators. It means that, in line with what Anna Robinson-Pant also defended during her lecture on ‘Inclusive Education: thinking beyond systems’, we aimed at potentialising the knowledge local communities already have and building upon that with them. The idea was that this initial gesture would unfold subsequent actions continuing to connect and to gather people. This hypothesis proved to be valid by posterior registers of networks formed during the summer school, one of which even evolved into an association to share experiences in management skills and to encourage small-scale businesses and agriculture among the youth in Gulu.

Considering our experiences in northern Uganda and the post-conference reflections, it becomes clearer that in a highly politicised terrain such as education within conflict-affected communities, the role assumed by international cooperation depends greatly on its agents and their attitudes and motivations. Democratic approaches that open conversational spaces and recognise one another as competent agents are essential to engage different actors and to create an inclusive environment. Furthermore, inclusion in education in post-conflict areas should represent a broader platform that binds the right to education to aims of reconciliation and peacebuilding. In a way, this is the novelty education represents in contexts of fragile peace: it informs new generations about other ways to resolve conflicts through dialogue and respect towards diversity.

Overall, the effort of presenters and organisers throughout the UKFIET conference to give a critical overview on the future of education comes in time for the next actions to be taken by academics and practitioners. Dilemmas in education policies show there are no ready recipes for education inclusion. However, multidisciplinary-oriented creativity and groundbreaking strategies are paving the road for new approaches to emerge. The conference reinforced the need to hear all actors involved in building a bright future for all beings in this planet through education.