This blog was written by Dzingai Mutumbuka, Chairman of the Zimbabwe National Commission for UNESCO, and Marla Spivack, RISE Research Manager and Research Fellow at Harvard University. The blog first appeared in the African Leadership Academy Newsletter, and then was published on the RISE Programme website on 23 September 2020. It draws on a recent RISE Issue Brief on education systems’ response to COVID-19.

We know that time away from school due to COVID-19 has undermined learning. Children are depending on education leaders – from high-level officials to classroom teachers – to start planning now for a new focus on foundational skills. With bold action, and clear focus education systems can mitigate the long term effects of this crisis and set out on a new course towards sustainable improvement in learning.

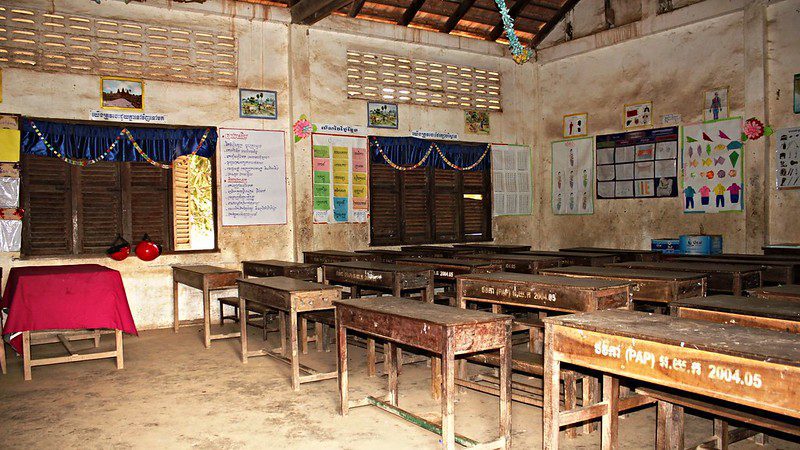

The global COVID-19 pandemic has upended our lives and our education systems. Education has been adversely impacted in two significant ways: schools have been closed, in some cases for a whole year; and economic production, the major source of education funding through budgets, has declined precipitously. In Africa, where there was already a learning crisis characterised by millions of children out of school and for those enrolled completing primary education without minimum competency in literacy – 86 percent of children reach the end of primary school without basic literacy according to the World Bank – and numeracy, COVID-19 school closures have turned the crisis into a nightmare.

Insights from research on education systems suggest that by making a system-wide commitment to prioritising foundational skills, assessing children’s learning levels when schools reopen, and adapting instruction to children’s learning levels, education systems can mitigate learning loss and even come back stronger than before.

Several features of the learning crisis set the stage for COVID-19 school closures to severely impact long-term learning outcomes. Learning profiles in African countries are flat, meaning that children acquire little new learning with each additional year in school. Many fail to master foundational skills early on and then struggle to keep up or catch up as the curriculum progresses. For children who learn little during school closures, catching up will be even more challenging. Learning levels in classrooms can vary widely and are likely to increase in the aftermath of COVID-19 closures.

COVID-19 closures are also poised to exacerbate learning inequality. The majority of children in African countries do not have access to virtual learning, but those that do are likely to be urban and better off. Better off children are also more likely to have parents who can support and supplement remote learning from the school system.

The curriculum in many developing countries is overambitious, setting out an agenda that teachers and students cannot effectively cover even in normal times. Learning recovery will be challenging as teachers must help students catch up with the curriculum while also teaching more diverse classes.

Projections and empirical estimates suggest that learning losses due to COVID-19 will be produced by a combination of stagnation in learning while schools are closed, and children continuing to fall behind even after they return to school. Learning losses now could undermine learning for years to come and impact later life outcomes including earnings, health, and empowerment. Therefore, education systems should prioritise helping children catch up quickly.

Children who fail to master foundational skills are the most vulnerable to long-term learning deficits. They are likely to fall farther and farther behind when schools reopen if the curriculum continues to progress at a pre-crisis level and pace. Going forward political and educational leaders should make clear that foundational skills are a priority, and articulate clear, achievable goals to reinforce this commitment. Education systems perform best when delegation is clear and consistent. With clear priorities education’s various subsystems – curriculum, workforce, exams and others – can more easily work together towards that goal. Clear delegation also allows frontline providers like school leaders and teachers to adapt to the challenges they face and deliver on those priorities.

When children return to school, education systems and teachers should prioritise using assessments to understand where children stand in foundational literacy and numeracy. Learning levels among children in the same class are likely to vary considerably, as students will have had differential levels of access to remote learning and parental support during the time away from school.

In order to get students back on track, it is critical that teachers know the learning levels of the students in their classrooms. Teachers will need resources and support to conduct diagnostic assessments. The approach should take advantage of high-quality assessments already in use. For example, instruments used by citizen-led assessment organizations can be adapted for use in the classroom. In cases where diagnostic tools are not available, an abbreviated version of summative assessments from the previous year could be adapted for this purpose.

As schools reopen teachers should focus on helping students progress in foundational literacy and numeracy rather than on moving through the standard curriculum, and progress should be measured in terms of student improvement, rather than against a curriculum standard. To achieve this, teachers will not only need information on students learning levels, but also the authorisation, resources, and capability to align teaching to be coherent with students’ growth needs, and the support to put new practices into action.

Approaches to adapting instruction can vary, and should be aligned with the existing system. For example, school leaders could decide to devote an hour a day each to review of basic literacy and numeracy respectively, or existing toolkits and targeted instruction programs can be adapted to be implemented in classroom settings. Adequate resources, toolkits, rapid training – some of which can be delivered remotely – should all be a part of the strategy. With clear goals and adequate support, teachers can be empowered to choose the practices that will work for their classroom.

RISE blog posts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or funders.