This blog was written by Mary Goretti Nakabugo, Executive Director of UWEZO Uganda; James Urwick, consultant for Uwezo Uganda; and Michelle Kaffenberger, Research Fellow with the RISE Programme and affiliated to the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford. This blog was originally written for and published on the RISE Programme website on 28 May 2020.

Introduction

Covid-19 has forced an unprecedented level of school closures, affecting more than 1.7 billion learners around the world. Now, a question of growing concern is how governments should be planning for the re-opening of schools. Education systems will have to deal with a multifaceted set of issues, from new health concerns and sanitation requirements, to remediation and making up for delays in essential learning. While schools are closed, many systems are introducing new resources for home-based learning, some of which may hold promise even after schools have been re-opened. Uwezo’s assessments of children’s learning and surveys of primary schools in Uganda, which include an assessment of school water supply, sanitation and hygiene, provide a unique source of insight on some of the critical issues that education systems may need to consider in planning for the re-opening of schools. Here we discuss findings from the surveys, as well as the Ugandan Government’s ‘continuity of learning’ efforts.

Implications of learning outcomes

The recent Uwezo assessment shows that, prior to the Covid-19 crisis, learning was already declining in Uganda. Between 2015 and 2018 the proportion of primary Grade 3 to Grade 7 children who could read and comprehend a basic Grade 2 level story in English declined from 39 percent to 33 percent. In mathematics, the proportion of this same group of children who could do primary Grade 2 division declined from 52 percent to 45 percent (Uwezo 2019).

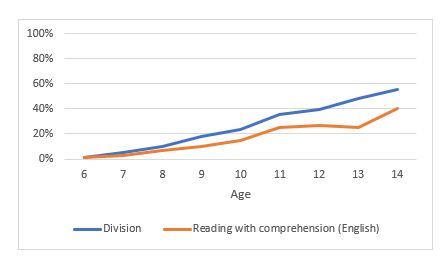

These declines reflect low absolute levels of learning as well. Examining children by age, among 10-year-olds less than a quarter could complete the Grade 2 level division problem, and only 15 percent could read a simple story with comprehension (Figure 1). By the age of 14, still only 55 percent have achieved basic numeracy, only 40 percent can read with comprehension in English, and 34 percent can read with comprehension in a local language.

The Covid-19 school closures will exacerbate an already-existing trend of low and declining learning outcomes. These results have important implications for education systems when schools reopen which relate to, but also transcend, the current crisis.

The first implication is that the curriculum and instruction will need to be adapted to the learning levels of the children upon return. While the government is undertaking efforts to maintain continuity of learning while children are out of school, doing so successfully will be a difficult task. But, even if these efforts are successful, children would still be far behind the expected learning level for their age or grade. Even best-case continuity of learning at the low learning levels achieved in school would leave many children far behind their grade level and unable to participate fully in school when they return. A 14-year-old who cannot read cannot engage with a secondary school curriculum.

Secondly, this presents an opportunity for education systems to reorient instruction to prioritize all children achieving foundational literacy and numeracy. As children’s return to school forces education systems to adapt instruction and undertake remediation on a scale never before experienced, they should use those efforts to ensure that all children gain foundational skills that enable later learning.

Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Health in Primary Schools

Social distancing seems almost impossible in primary schools, but a disciplined approach to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) in schools can help to reduce infections. Uwezo’s 2018 survey of primary schools in Uganda, which accompanied its national assessment of children’s literacy and numeracy, provides useful insights related to WASH.

Contrary to government regulations, half of primary schools did not have a hand-washing facility near the toilets (Uwezo’s national estimate) and only 24 percent of all schools provided a hand washing facility with both water and soap. The casual attitudes of many school administrators to hygiene need to change urgently, especially as the number of handwashing facilities per school may need to be increased in the context of Covid-19.

Sanitation problems were also common at surveyed schools. Toilet provision for pupils in Uganda had improved since 2015, with a mean pupil-toilet ratio of 58:1 (weighted national estimate). However, 26 large schools, in the sample of 879 schools, had more than 200 pupils per toilet – and needed emergency action to provide more toilets.

Provision of safe drinking water is also important for children’s health. In 2018, for the first time, Uwezo’s citizen volunteers tested schools’ drinking water using H2S test kits, in addition to recording the main type of water source, whether the water was treated for drinking, and the methods of treatment used. The tested drinking water was found to contain bacteria in 49 percent of primary schools (a weighted national estimate). There was a high incidence of bacteria in water from wells (used by about 16 percent of schools), as well as water from rain catchments, streams, and lakes (used by 9 percent of schools). On the positive side, half of the schools used boreholes, which had a lower incidence of bacteria. About 57 percent of schools surveyed did not treat water for drinking.

Uwezo’s findings on general health facilities show that 55 percent of primary schools had a supply of medicines, 54 percent had a stocked first-aid kit, 69 percent had a supply of sanitary pads, and 75 percent had received recent training on menstrual hygiene. Nearly all schools had appointed Senior Woman and Senior Man Teachers who were tasked with the responsibility for gender-related health and welfare issues – an encouraging development. Given the heightened focus on health following the COVID-19 crisis, these roles may need to expand beyond gender-specific health issues as children may have more questions than ever about general health issues that teachers will need to be prepared to address.

Lessons from Uganda’s Continuity of Learning Framework

In April 2020, the Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) in Uganda developed a framework for continuing learning during the Covid-19 lockdown and school closure. The immediate focus of the framework is the ‘provision of remedial lessons targeting topics that could have been covered by learners while at school’. It is understandable that in emergency situations there is urgency to address the immediate need – in this case, the need to maintain some learning continuity. The MoES should be applauded for this swift action. What could have been even more beneficial and cost-effective was to develop materials to support learning at home beyond the first term and the shutdown. Nevertheless, the framework contains practices that may be worth carrying forward even after schools reopen:

- A multi-media approach: Uganda has instituted one of the most equitable education responses to Covid-19. The learning continuity framework embraces a multi-media approach to delivery of learning materials through radio, TV, online and print materials. This strategy of reaching all learners irrespective of their social and economic status and geographical location should continue beyond Covid-19.

- Distribution of print materials: This is an opportunity to continue making printed learning materials available to households, even after schools reopen. Many children interact with printed materials only at school, yet children who have reading materials at home and use them usually learn better than their counterparts without them (Abuya et al and Oketch et al).

- Encouraging parental engagement: The framework highlights the fact that its success will depend on the support and participation of parents, guardians, and other adults at home in terms of creating time for children to learn and supporting them on challenging tasks. Encouragement of parental engagement should continue beyond the lockdown. Evidence on basic learning in Uganda indicates that literacy and numeracy competency levels are higher for pupils whose parents are actively involved in their education.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic and associated closure of schools create new challenges for educational systems, especially those that were already struggling to provide a service of acceptable standard. The case of Uganda illustrates the situation in many countries, highlighting some of the key areas to be considered prior to schools reopening. Systems should begin planning now to ensure schools can provide appropriate learning opportunities to returning children, offer safe and healthy school environments with adequate hygiene provision, and maintain beneficial elements of their continuity of learning efforts.

we pray for the mercy the good lord has presented to us this challenging time.

opening for the covid institutional survey examinations will give us a start for next year

This insightful blog highlights critical considerations for reopening schools post-COVID-19 in Uganda. It effectively addresses challenges in learning recovery, WASH practices, and educational reforms essential for ensuring safe and inclusive schooling environments.