This blog was written by Paul Miller, US Country Manager at Whizz Education and originally published on the Whizz Education website on 13 May 2020.

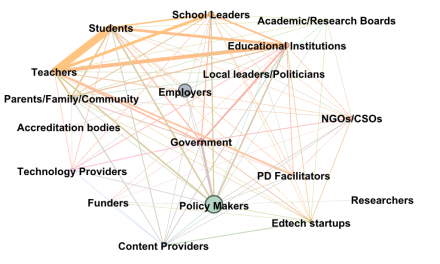

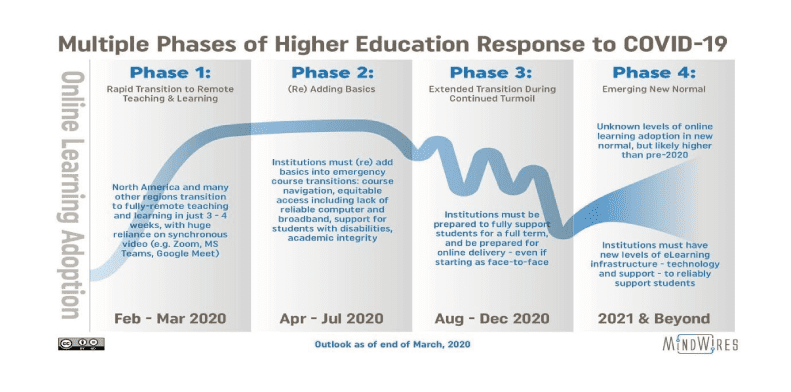

Across the world, governments have responded to the ongoing transmission of Covid-19 by undertaking extended school closures and encouraging school systems to transition to remote learning. These transitions have taken place in phases and many school systems have now advanced from an initial ‘Phase I’ plan focused on emergency response to a ‘Phase II’ plan focused on effective delivery of remote instruction.

Schools across the world are responding to COVID-19 through phased transitions to blended learning. Source: Mindwires

These measures have been informed by recommendations from public health authorities, and are aimed at preventing local communities from emerging as new COVID-19 epicenters. As schools prepare for an extended transition period leading to an emerging “new normal”, they are discovering that they are faced with a new challenge- one of seismic proportions.

To ensure equitable outcomes for all students, educators are increasingly finding that they need to shift their attention to addressing the possible ‘aftershock’ of several months of lost learning data.

The US Department of Education announced on March 12th that it would consider targeted waivers of federal testing requirements due to COVID-19. Eight days later, following recommendations from the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSO), as well as the School Superintendents Association (AASA), broad waiver authority was granted, and by the end of the month all 50 US states plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Bureau of Indian Education had received exemptions from national assessments. Schools in the United Kingdom followed a similar trajectory. By March 18th all primary and secondary assessments (e.g., Key Stage exams, GCSEs, A-levels) were cancelled for the 2019-2020 school year.

The logic behind cancelling these high-stakes exams was compelling. It ranged from pragmatic concerns expressed by state-level authorities about the validity and reliability of assessments taken amidst a global public health crisis, to more empathetic concerns, such as those expressed by the US Secretary of Education, that “neither teachers nor students need to be focused on high-stakes testing at this time.”

Other countries have pursued different approaches. Kenya’s Education Cabinet Secretary Dr. George Magoha announced in mid-April that there would be no cancellation of national assessments, currently scheduled for October and November. The Kenya National Union of Teachers (KNUT), while encouraging stringent COVID-19 prevention guidelines, has endorsed the idea of prioritizing school access for candidates sitting for the state exams as leaders chart a roadmap to re-open Kenyan schools.

Regardless of where different governments land on the question of whether to administer standardized assessments in 2020, they are already all united by a common challenge- the loss of key learning data that can inform planning and instruction.

Critically, standardized testing results are not the only learning data that has been lost during the COVID-19 pandemic. As school closures have been extended, often through the end of the academic year, access to student learning data from formative assessments and end of course exams has correspondingly been limited.

What is the impact of a large-scale loss of learning data at the school level? How intense can these aftershocks be?

A loss of learning data equates to a loss of learning itself. At an individual school-level, rigorous empirical evidence suggests that the resulting constraints on data-based decision making may come at the cost of a full month of learning for primary school students. This deficit will only compound well-known challenges caused by summer learning loss which, in the absence of effective interventions, will strip students of an additional 1-2 months of learning and exacerbate income-based gaps in student achievement.

For practitioners trying to plan for the ‘new normal’ when students return to school following the extended closures these aftershocks are experienced as a disruption to standard routines. How should school administrators plan master schedules without student learning data to inform placement? How can teachers prepare to differentiate instruction with limited data or insights into the specific needs of their pupils? Faced with these challenges some school systems have proposed having students repeat a grade, although a growing body of evidence suggests grade repetition can create even greater adverse impacts- in particular for the most vulnerable and economically disadvantaged students.

What is promising is that the strategic deployment of intelligent teaching and learning solutions can minimize many of these risks and challenges. AI-enabled adaptive learning platforms such as Math-Whizz have the ability to generate real-time data that can support individual instructional decisions, as well as informing school, district-level, and national planning. As students complete lessons tailored to their individual needs and pace of learning, educators can access real-time reports that help them understand students’ mastery of core skills and concepts aligned to rigorous content and practice standards. By leveraging adaptive learning technologies in this manner schools can plan for reopening better prepared to ensure equitable access to opportunities for learning and achievement.

To be clear, there is no silver bullet or playbook for responding to the current pandemic. Overcoming all of the new barriers to learning created by Covid-19 is complex. It requires localised solutions, developed in partnership with key education stakeholders. The hopeful view is that even if the initial upheaval from Covid-19 was unavoidable, the aftershocks of lost learning data may be more manageable with thoughtful planning and the strategic deployment of proven technology solutions.

The Great Nobi earthquake (1891) was followed by more than 3,000 smaller quakes in the succeeding 12-14 months and led to the first major empirical research on aftershocks. Contemporary geological research has shown that aftershocks can extend for generations. Source: Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.