This blog is based on the introduction by Yvette Hutchinson to the new British Council book ‘Creating an Inclusive School Environment’. The blog was written by Deborah Bullock, Freelance ELT consultant, writer and editor, and highlights some key activities taking place around the world to address inclusion when working with minority ethnic groups in the classroom.

What do we mean by minority ethnic groups?

The term minority ethnic is often used in the UK to describe people of non-white descent. However, issues of minority access and engagement are consistent across countries, economies and cultures. The papers in this book, for example, highlight the issues faced by university students from marginalised communities in India, young migrant learners, and learners from indigenous communities in Namibia.

The term minority ethnic is often used in the UK to describe people of non-white descent. However, issues of minority access and engagement are consistent across countries, economies and cultures. The papers in this book, for example, highlight the issues faced by university students from marginalised communities in India, young migrant learners, and learners from indigenous communities in Namibia.

| ‘Marginalization in education is a form of acute and persistent disadvantage rooted in underlying social inequalities. It represents a stark example of ‘clearly remediable injustice’. (UNESCO Education For All Global Monitoring Report 2010) |

Underlying issues

Cases of minority ethnic groups outperforming their peers are rare – rather evidence points to a lack of engagement in the classroom, slow progress and underperformance in assessments. Why? One reason is unconscious bias – ‘an inflexible positive or negative prejudgement about the nature, character and abilities of an individual, based on a generalised idea about the group to which the person belongs.’ (Thiederman, S (2003). Making diversity work. Chicago: Dearborn)

In an educational setting, if left unchallenged, unconscious bias can significantly impact a practitioner’s attitudes and behaviour, often resulting in a lowering of expectations of a particular learner or group of learners. Faced with minimal expectation and a lack of challenge, such learners can easily become disengaged from learning. However, low expectations are not the only issue. Learners from minority groups bring with them a cultural heritage and identity which is often ignored or dismissed. Unless we recognise and understand this, how can we deliver learning experiences that are relevant, meaningful and of benefit?

What approaches are being advocated to ensure learning is relevant, meaningful and beneficial to minority ethnic groups?

In Creating an inclusive school environment we find three case studies which illustrate how educators are endeavouring to make learning relevant, meaningful and beneficial to minority groups:

At the Ambedkar University Delhi (AUD) a series of interventions have been introduced over the past seven years to meet the needs of students from marginalised communities whose schooling has not prepared them fully for the rigours of academic life. Such students belong to socio-economically disadvantaged communities, are often low caste and first-generation university students, have limited means to critically engage with classroom discourse and reading materials, do not have the requisite training in thinking and critiquing, and to top it all, their proficiency in English (the medium of instruction) is poor.

The main focus of these interventions has been on English language acquisition, resulting in the development of a bridge programme, the English Proficiency Course (EPC). Marking the transition from school to university, it helps develop learner confidence and familiarity with the language in social contexts. In addition, out-of-class support initiatives such as the mentorship programme and the Buddy Scheme have been introduced. Student stories reveal that teacher and peer support and empathy can encourage and sustain the English language learning endeavours of students for whom English is not just a language but a means of achieving access to better opportunities and a way out of years or even centuries of discrimination and denial.

| ‘When I came to this university it seems everyone is speaking in English not even one uses Hindi language, firstly I was afraid, but I thought this environment could be an opportunity for me to learn English. I started learning English, but my single effort was not enough. I got EPC in first semester, this course helps me a lot to improve my English, by daily reflection, writing and assignment. I also got a mentor for my help. They all help me a lot, made me capable.’ (Uday, student) |

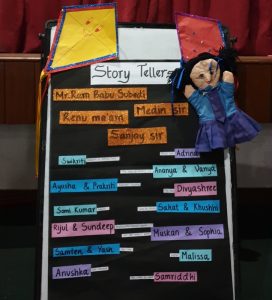

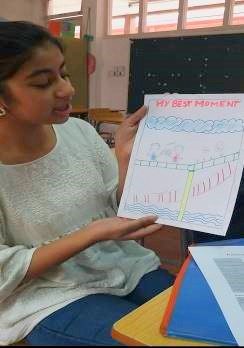

Narrating their own tale of delivering storytelling workshops, the authors discuss the importance of embedding such practice into the curriculum and the impact of personal narration and validation on young migrant learners. There are numerous benefits of storytelling included here, e.g. for promoting inclusivity among different groups and newly arrived learners:

| ‘Minority ethnic students retrieve their cultural knowledge and have a too rare opportunity of contributing their valuable knowledge in the classroom. Thus, they gain motivation and confidence.’ (Irmgard Kreienkamp, Senior teacher trainer at the Landesinstitut in Hamburg) |

The authors illustrate how storytelling promotes students’ respect for their own and others’ cultures, how it helps the teacher to create a collaborative learning space where learners listen to and understand others’ perspectives, and in so doing brings the classroom and wider community together.

The authors illustrate how storytelling promotes students’ respect for their own and others’ cultures, how it helps the teacher to create a collaborative learning space where learners listen to and understand others’ perspectives, and in so doing brings the classroom and wider community together.

| ‘Speaking is an art. Storytelling is, without a doubt, the oldest of all arts. It can create imaginary worlds like music or painting art do. What makes storytelling special for me is, that it has enormous potential to fully develop the learner from the inside out.’ (Alla Göksu, co-author) |

| ‘You see what formal education has done to us. You told us we must take our children to school. We sent them but the system could not keep them. They then dropped out. They are here and unemployed. Now they have lost on the knowledge from formal education and they have lost the traditional knowledge. What will become of us the San, if this formal education ejects our children?’ (Khwe elder, Bwabwata from Matengu, K (2008). Lecture field notes prepared for the Course: Rapid Research Appraisal. Windhoek: Cheetah Conservation Fund) |

In Namibia, various issues arise for the San and Ovahimbo peoples who, as hunter-gatherers and cattle specialists respectively, hold dearly to indigenous learning as the most suitable preparation for young people from their communities. By examining social patterns and culture, reasons for low education outcomes, practices in schools to enhance inclusivity, and educators’ perspectives on the San and Ovahimba children’s participation in education, the authors suggest Culturally Responsive Teaching is a positive way forward for marginalised groups. They advocate the adoption of cultural sensitivity and the avoidance of having low expectations of learners from indigenous communities, and teacher education which emphasises that all learners are valued and enabled to succeed without having to give up their cultural value systems. They also argue for re-thinking inclusive education by bringing to the forefront the advanced needs of indigenous communities and bridging the gaps between formal and traditional education.

| ‘Rather than being a marginal issue on how some learners can be integrated in mainstream education, inclusive education is an approach that looks into how to transform education systems and other learning environments in order to respond to the diversity of learners.’ (from UNESCO (2008). Inclusive Education: The way of the Future. Outcomes and trends in Inclusive Education at Regional and Interregional levels: Issues and Challenges. ICE Preparatory Workshops and Conferences on Inclusive Education. Paris: UNESCO) |

Further information on each programme can be found in the British Council publication Creating an inclusive school environment, edited by Susan Douglas, 2019.

This blog is the second in a series based on the new British Council book. This first can be found here: Creating an Inclusive School Environment: Displaced Populations.