This blog was written by Laterite, who are carrying out a range of high-frequency phone surveys across East Africa to understand the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 on different groups, including firms, households, adolescents and coffee farming households. In the coming months, Laterite will share insights from their experience with phone surveys in East Africa. This blog was originally published on the Laterite website.

Face-to-face data collection isn’t possible during COVID-19 – so how do phone surveys measure up?

Face-to-face data collection isn’t possible during COVID-19 – so how do phone surveys measure up?

The coronavirus pandemic presents researchers with a paradox: high-quality data collection plays an important role in shaping the response to the crisis, but lockdowns and bans on movement limit how researchers can collect data.

The Laterite team is committed to complying with public health advice and is adapting to the challenges. Under these circumstances, data collection can no longer rely on enumerators traveling to hear first-hand accounts from communities. This means that traditional face-to-face data collection is out, and phone surveys are in.

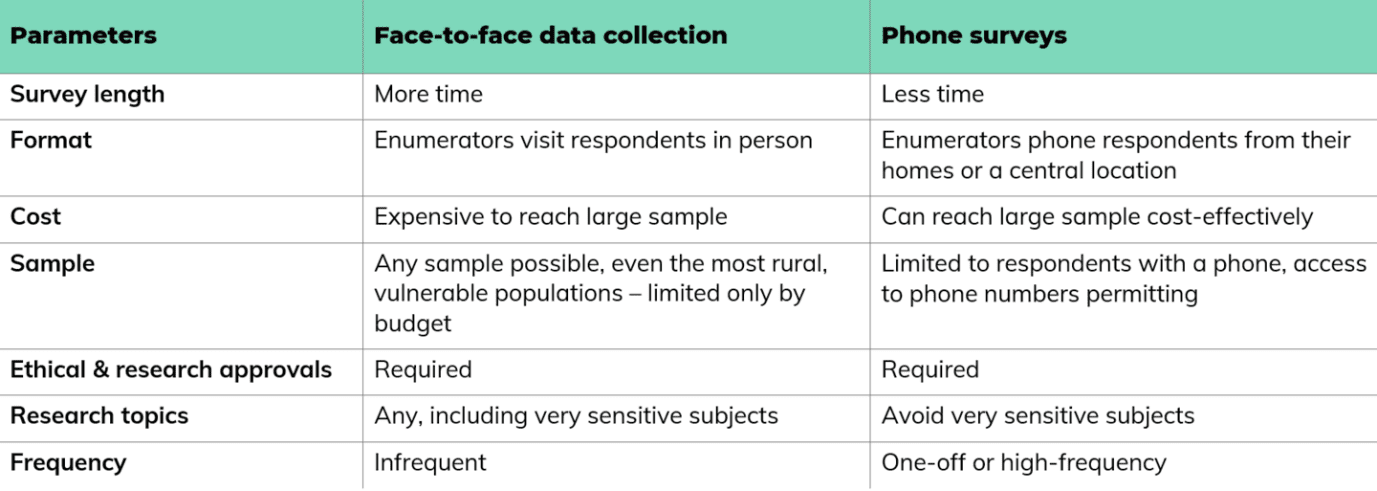

Phone surveys can be extremely effective: they don’t require travel, they are quick to administer, and they are well-suited for high-frequency data collection campaigns designed to monitor variables in a population over a given time period. On the other hand, phone surveys are not a data collection panacea suitable for every research question.

So what needs to be considered when deciding if a phone survey is appropriate?

1. Consider your sample.

Phone surveys can reach a much larger sample than can be achieved by sending enumerators to respondents’ houses, and at a much lower cost. But with this advantage comes an obvious constraint: people without a phone number can’t be contacted for a phone survey. In our experience working in Ethiopia over the last five years, we have seen that around two-thirds of people in rural areas have access to a phone, compared to almost everyone in urban areas. Vulnerable populations, such as those with a disability, lower incomes and/or lower educational attainment, are also less likely to have access to a phone. Male respondents are more likely to own phones than female respondents, so surveying by phone can introduce a gender bias.

Further, obtaining these phone numbers can be a challenge: since it’s not possible to conduct robust listing exercises at the moment, researchers are often reliant on past survey samples. These samples can be out of date or incomplete. These factors mean that samples might not be representative, which must be taken into account in the research design and data analysis.

2. Time is not on your side…

A typical face-to-face interview allows the enumerator time to build rapport with the respondent and develop a relationship of trust. To carry out a phone interview, on the other hand, the enumerator must phone the respondent and introduce themselves sight unseen, which can make it challenging to build a relationship of mutual trust. There is also no opportunity for questions relying on open-ended responses or non-verbal cues. To maximize the chances of the respondent staying on the line to complete the survey, phone surveys must be short and sharp, ideally around 10-20 minutes in length.

3. … but frequency is.

While carrying out repeated face-to-face surveys of the same population is a complex and expensive exercise (think: baseline and midline studies), phone surveys offer the possibility of high-frequency data collection. High-frequency phone surveys allow for the collection of regular, real-time insights on the same population over a period of time, a good choice for studying how people are faring in dynamic situations (such as a global pandemic). SMS surveys, either as the primary data collection tool or as a supplement to phone surveys, can also be used to send reminders to participants to bolster response rates.

4. Ethics and privacy are paramount.

Just because phone surveys are short doesn’t mean ethical and research approvals are optional. On the contrary, it’s important to double down on these to ensure that survey protocols are ethically sound and referral procedures are in place. Likewise, it’s as important as ever to obtain consent from participants, but this must be done verbally rather than in person. For face-to-face surveys, time is invested in explaining the project to a household and collecting their consent in writing before the survey takes place. It is more difficult to explain the purpose of the survey over the phone, so it’s important to invest extra effort in ensuring that participants understand the research objectives before they agree to participate. There may also be issues with privacy, as the enumerator cannot be sure that no one is listening in to the call on the other side. This means it is not appropriate to discuss very sensitive subjects in phone surveys.

Remote data collection will play an important role in informing the response to the COVID-19 crisis and Laterite has capacity in place to roll out phone surveys in Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. By being aware of the limitations and putting ethics at the forefront, we can ensure the data we collect is robust, practical and useful for policy-makers.

Summary: Considerations for phone surveys

Due to the limited number of available data collection methods, they can be reused, which tires the respondents. Survey fatigue can be a direct result of poor coordination between agencies, as the same data is collected from the same people. The COVID-19 situation requires additional efforts to ensure good coordination of data operations and effective and responsible information sharing.