This blog was written by Seema Nath, Doctoral Candidate and member of the Cambridge Network for Disability and Education Research (CaNDER), Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. It is part of a series from the REAL Centre reflecting on the impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on research work on international education and development.

Schools around the world are experiencing extraordinary times and as education moves online, those who have historically faced marginalisation find themselves facing new challenges to access education. The present pandemic situation is disproportionately affecting those within marginalised communities in India and across the globe. In education, these disadvantages are amplified for learners with disabilities belonging to low socio-economic backgrounds. Therefore, we need to learn lessons from schools that are incorporating the principles of inclusion and social justice while approaching these challenges.

In order to understand how some schools are continuing to reach to the most marginalised, I held an online focus group via Zoom and eight phone interviews with members from seven schools operated by the NGO Muktangan Education Trust, under a public private partnership with the Brihan Mumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC or Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai) in Mumbai, India. The members interviewed included subject teachers, learning resource teachers (teachers trained in special educational needs), faculty members and members of the leadership team. These schools cater to low-income families: the majority of teachers and students live in crowded neighbourhoods, with multiple family members staying in a single room and shared toilets between multiple households. These families are some of the worst hit by COVID-19 in Mumbai.

All interviewees emphasised the need for ensuring wellbeing of the school community. As the crisis unfolded, students, parents, teachers and the rest of the staff have grappled with issues of unemployment in their families, fear and anxiety regarding survival for many – from the virus or loss of livelihoods, uncertainty surrounding the future, many teachers have become sole bread-winners, etc. For parents of children with disabilities, it also meant a loss of carefully orchestrated routines they have developed, inability to access medical facilities and loss of occupational therapy for their children as government hospitals are overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients.

Teachers are regularly sharing handwashing and physical distancing guidelines adapted for individuals living under circumstances where access to running water is limited and they are in proximity that makes physical distancing difficult. For example: learning resource group (LRG) teachers are sending flashcards to parents of students with disabilities through WhatsApp that they can make at home and are adapted to address the needs of the students so that they can guide them on hygiene practices and explain about COVID-19.

They are reaching out daily to students with difficulties and disabilities and their care-givers to give mental health support. Some students who require additional support are called twice a day – at the beginning of the work day to touch base and give supporting instructions for the lessons and in the evening to enquire and get feedback about the day or about any challenges they are facing. For other students they make one call a day. For example, initially one of the students with autism was finding it difficult to adjust to the sudden change in routine, resulting in reluctance to engage with anything, waking up late in the morning, causing both the student and parents distress. So the LRG teacher made a timetable for the student with the parent’s support, suggested she wear her school uniform every morning as she did her schoolwork even if she did not come to school and set some basic goals for both the student and the parent and kept following up on them.

In order to promote mental and socio-emotional wellbeing, the socio-emotional department and members of the leadership team are reassuring the school community that uncertainty over all aspects of life, and living with so many family members cooped up in a small space while being involved in care work, can be taxing on the mental wellbeing of students, teachers, and the parents. They are doing this through various online workshops and by opening up group sessions for ongoing lesson planning or English proficiency classes for discussion on mental health and socio-emotional wellbeing. The teachers in turn encourage parents and students to talk about their feelings and emotions, and share their fears and daily accomplishments. In many cases, the gender divide in care responsibilities, doubled with teaching responsibilities, is acute for both teachers and parents and the school is mindful of this. The study timetables and calling schedules are prepared keeping their needs and household responsibilities in mind.

At a time when mental health and socio-emotional learning has found its mention in India’s education strategy to address COVID-19 disruptions to education, it is worth noting how it is being practiced on the ground by low-resourced schools catering to students and teachers from marginalised backgrounds.

Access to infrastructure and technology: The major challenges highlighted related to accessing smart phones, phones, weak mobile network, difficulty buying mobile data (data recharge), etc. On one hand, due to availability of low-cost smart phones and the proliferation of messaging services like WhatsApp, increasingly, households have access to technology but it is mostly the male members who have this access. Additionally, a single family might have multiple members who need to access education in this manner. Hence there is a tussle to share one resource between multiple members of the household.

In consultation with parents, teachers are ensuring that the students receive fair access to the phones for education purposes. If smart phones are unavailable in a household, they are devising ways they can send the teaching instruction on the phone through a call or text messages. For students with some disabilities, the teacher mentioned that studying via a screen is a challenge. So the LRG teachers suggested subject teachers to incorporate phone usage alternating with hands-on tasks in their lesson planning. For example, children engage with the phone for 15 minutes and then have a hands on activity for 30 minutes.

Parents as home-school facilitators: As education has moved to online modalities, teachers have needed to enlist the support of the parents to help with the education at home. Parents of most students have varying literacy levels and the medium of instruction at school is English; for most parents who have not gone to school or studied in a local language, supporting English language education is challenging. Recognising this the teachers are helping parents to support their child’s learning by accompanying the learning materials with an audio clip of instructions in Marathi or Hindi for the parents. This way parents are included in their child’s learning and aware of what their child is expected to do and can support them in the learning activities at home.

One of the priorities, according to the LRG departmental leader, is to ensure the continued inclusion of children with disabilities in whole-class teaching and learning. The subject teachers continue to make lesson plans for all students. They have created WhatsApp groups through which they share each day’s lessons, activities and set learning tasks. For those who do not have access to WhatsApp, instructions are given through text or phone calls. The subject teacher calls each student to speak with the parents and students on a regular basis and collect feedback on their experiences.

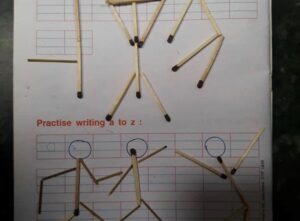

At the lesson design stage, the departmental heads closely supervise and give feedback to the teachers about the contents in the lesson plan. They ensure that they are simple and not time-consuming, and adhere to the learning goals. This process ensures that the lesson plans continue to cater to students who have challenges in accessing study materials at home or students who have different learning needs or disabilities. To ensure that students continue receiving academic support for all subjects and parents and teachers can support them without overwhelming them, a separate subject is scheduled for each day of the week for the different grades. For example; English on Mondays, Mathematics on Tuesdays and so on.

The LRG teachers voiced concerns about the loss of learning gains and progress for the students with difficulties and disabilities as face-to-face classroom support stopped. To continue one-on-one support, they send a demo video with instructions for the parents and students about the lessons set by the subject teachers if they have access to a smart phone. If this is not possible, they call and take the students through the steps. They mention being mindful of the student’s living conditions, their needs and the resources they have access to while designing various learning activities. A concern has been about the lack of space for play or exercise as the students are confined to their houses and especially for students with difficulties and disabilities. To address this, the teachers have started incorporating song, dance and movement activities in their lesson plans, to ensure that the students get some exercise even if they cannot step out of their house.

The move from school-based education to online and distant learning has come suddenly and teachers and students have needed to adapt rapidly to these changes. Many school buildings where the schools run by Muktangan are located have been turned into quarantine centres for the people exposed to COVID-19 in those areas, as home quarantine is not possible for families living in rooms measuring 10 x 10 sq. metres. Moving ahead, the schools’ plan comprises of:

Technology mapping: They are conducting surveys to find out how many students will continue to have access to smartphones once their parents return to work. Thereafter, they are exploring avenues to ensure that students have access to smartphones or phones. In addition, they are familiarising parents and helping them download the Diksha app developed by National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) and supported by the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), Government of India. This app has been recommended by the government education department, and the schools are mainly using it to enable students to access textbooks in the new academic year that begins mid-June.

Training of teachers in the use of online platforms and distant learning pedagogy: There is recognition that online pedagogy is different from classroom pedagogy and there is a need to adapt teaching and learning practices to online and distant learning. Presently, all of the teachers are receiving training on the use of various online platforms to supplement teaching and learning and the application of online and distant learning pedagogy.

Reviewing the curriculum to adapt it to distant and online learning: In the short term, the teaching staff are distilling topics in each grade from the curriculum that lend to teaching and learning in the distant learning or online learning mode. In the long term, they are re-looking at all the concepts within the curriculum for each grade and adapting them to deliver through these new modalities, in case the students are unable to return to school for a long time. As all students have inequitable access to resources for teaching and learning, the focus of the curriculum goes beyond academic learning outcomes ,according to the school leadership team. The emphasis is on the acquisition of 21st century skills and the development of empathy and critical thinking.

Community participation: A major focus is on fostering community participation and tapping into the resources of the community. The schools are partnering with other NGOs, government agencies and resource partners where possible to optimise their capabilities and to lend their expertise where needed.

These school have many concerns: the unavailability of some of their school buildings for an extended time; the uncertainty around when regular schools can start again; the challenges of parents to access the basic needs for their children, like food and shelter; possible migration of the students and their parents back to their villages, thereby discontinuing their education here and possibly some never accessing it again; long term home schooling support for children with disabilities; etc. However, as one teacher summed up, ‘It is what it is. All we can do is ensure that we look after each other and do the best we can. We hold hope that someday things will return to normal and we will be at school again just like before. Till then our school leaders help us, and teachers are teaching, and we treat everyone as part of one family.”

———————————–

Note:

- The teachers who provide support to students with difficulties and disabilities are called Learning Resource Group (LRG) teachers.

- I have a long-standing rapport with these schools as they are the site of my ongoing PhD research.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank the members of the school who took out time out of their busy schedule to share how they are supporting students during these times and their plans ahead. I am thankful to Prof Nidhi Singal for her editorial support.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks