This blog was written by Ricardo Sabates, Reader in Education at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge and member of the REAL Centre, and Emma Carter, Research Associate at the REAL Centre. This blog is part of a series from the REAL Centre reflecting on the impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on research work on international education and development.

Across the world, countries are facing unprecedented and changing times in trying to support the education of millions of children outside of schools. Several methods for reaching children at distance have been implemented in diverse countries, ranging from the use of radio and television in locations of limited internet penetration to full online provision for the better resourced schools. The use of off-line educational resources has also been central to delivering education to the most marginalised students, whether this is with self-instructional printed based materials to supplement textbooks, or exercise books. How much children will learn during this time remains unknown, although it is expected that the poorest will be hit the hardest.

How are school closures affecting marginalised children?

A number of recent blogs have described many groups of marginalised children who are expected to suffer most due to school closures. In the case of Kenya, girls in rural marginalised communities and refugee children in camps are learners likely to face consequences as a result of COVID-19. In Ethiopia, girls from the poorest rural households may be at higher risk of sexual exploitation, early marriage and labour, all which will impact their future learning possibilities. Children living in stressful home environments, as well as children who experience stress and anxiety as a result of school closures, are also likely to be negatively impacted in their opportunity to learn. This is partly due to their own emotional instability as well as their lack of a supportive home learning environment. Children with disabilities are further expected to be at a high risk, not just of having limited learning opportunities through inclusive online platforms, but also through reduced support from health professionals currently focused on the COVID-19 crisis.

We do not argue against the higher risks faced by these and many other children who are in a position of relative disadvantage. Researchers in the field have solid historical and empirical foundations to support the claims made in these and other blogs and published on social media platforms. Yet, it is unknown how much learning is likely to be lost as a result of school closures, what the role of the home environment may be, and what the expected learning recovery will necessitate once schools resume (obviously under new social distancing rules).

Estimating the learning loss

In an attempt to shed some light on these unknown factors, we provide an estimate of the potential learning loss which happens when children transition from one school year to the next. In most countries, children spend between 6 to 9 weeks of what is known as a “long school break” between the end and the start of the academic years. It is this transition time that we use to measure learning loss.

Results below are for out-of-school children who entered the Complementary Basic Education programme in Ghana in the academic year 2016-17. At the end of that academic year, children spent about 3 months out of school before making the transition into a government school for the academic year 2017-18. By measuring foundational numeracy skills at the end of the CBE programme in June 2017 and again in October 2017, at the start of government school, we are able to estimate learning loss during this period. Our estimation of the learning loss serves as an indication of what is expected, as a minimum, from the current school closure situation in Ghana.

Similar estimates are being provided by colleagues in RTI. They are also measuring learning in two consecutive school years and estimating how much learning loss is expected due to the transition time. While their work will be cross-national, we focus here on marginalised children who accessed complementary education and transitioned into government schools in Ghana. We also provide insights into children’s motivation for learning as well as home learning resources as potential factors which may impact on the equity dimensions of learning loss.

The context of Complementary Basic Education

Complementary Basic Education (CBE) is a programme initiated by School for Life (SfL) in 1995 and scaled up in 2013, with support from the Department for International Development (DFID) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The CBE programme provides nine months of accelerated learning in basic literacy and numeracy in eleven mother tongue languages. Classes are set up in remote and deprived areas for children who would normally be unable to attend school. Children are generally aged between 8-14 years and the curriculum aims to equip them with the knowledge and skills equivalent to those learnt in the first three years of formal school. Following completion of the CBE, children transition into nearby primary schools at a grade level compatible with their achievement at the end of the programme.

We assessed foundational literacy and numeracy skills for children who undertook the CBE programme during the academic year 2016-17, both at the beginning and at the end of the programme. After the transition into government schools, children were re-assessed again at the beginning and at the end of the first school year. For the results below we use information from 1,166 children for whom we have complete assessments over the course of these two academic years.

Measuring numeracy

We use foundational numeracy skills over time to measure learning loss during the transition from CBE into government schools. The learning assessment used for the four rounds of data collection were based on the Early Grade Mathematics Assessment (EGMA) for numeracy. EGMA was designed to provide information about basic reading, writing and mathematics competencies — those competencies which should typically be mastered in the very early grades of primary school and without which, pupils are likely to struggle to continue to achieve higher academic competencies.

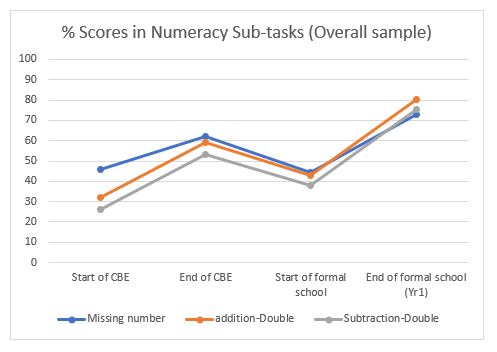

Due to minor differences between the assessments used in the first and second year of data collection, we only use results from missing number identification, two-digit addition and two-digit subtraction which were comparable over time. We estimate the percentage of correct responses in each of these tasks and aggregate across to generate a score of numeracy proficiency.

Learning gains in numeracy during CBE programme

Our results revealed important gains in foundational numeracy skills during the nine months of the CBE programme (October 2016 to June 2017). For example, at the beginning of the programme, 46% of students achieved correct responses in missing number identification and at the end of the programme, 62% achieved correct responses. In terms of addition and subtraction, at the beginning of the CBE programme, only 32% and 26% achieved correct responses in each of these numerical tasks, respectively. At the end of the programme, 59% and 53% of children achieved correct responses in addition and subtraction. Overall, the learning gain across all tasks was a 27 percentage points increase during this period.

Learning loss due to three months not in school

But was there any learning loss between June 2017 and October 2017, that is as children finished their complementary education and moved into a government school? When children were re-assessed at the beginning of the first year in government schools we found a significant reduction in numeracy skills. This reduction was equivalent to 18 percentage points, which means that 66% of the learning gain during the CBE programme was lost, as illustrated in Figure 1.

More striking are the differences that we found according to key factors that constrain home learning, which during the current COVID-19 crisis are extremely relevant. Among these, we found:

- Children who did not have books or reading material at home, or access to reading activities, had a learning loss equivalent to 100% of the previous learning gain. Those who had these only experienced around 58% learning loss.

- Children who never asked adults for help in the household when they did not understand things at school had over 90% learning loss. Those children who did seek support had a learning loss of only 34%.

- Children who responded that they were not given enough time to study and review at home had a learning loss of 81%. Children who were given this time had a learning loss of 65%.

- Children who lived in a household without a mobile phone or tv had a learning loss between 80 to 90%. Those with these assets had a learning loss of only 40 to 50%.

- There are no differences in relative learning losses for children living in households which had access to radio.

Our previous published research on the CBE programme has also shown significant learning losses for particular children. For instance, that learning loss over the three-month period was particularly harmful to low achievers. Similarly, a significant learning loss was found for children who changed language of instruction as they transitioned into government schools.

A bright future?

Even without the pandemic, our estimate of the learning loss due to time not in school for disadvantaged children was significant. On the bright side, our analysis showed that children who actually made the transition and remained in school managed to overcome the loss and actually continue to improve in foundational numeracy. At the end of the first year in government schools, the achievement in missing number identification for all children increased to 73% correct responses. In terms of addition and subtraction, the percentage of correct responses increased to 80% and 75%, respectively. These are substantial gains that are not just recuperated, but also enhanced if children remain in schools.

Inequalities will remain in terms of the children who may be able to catch up in their learning after the transition into government school. As we expect, not all children will return to school after the long school closure. In fact, the expectation is that the current COVID-19 situation will increase economic pressures on households, which will impact on their ability to send children to schools. As we have shown, the provision of off-line reading materials and activities at home could be one way to limit the learning loss for many children who are likely to remain out of school for the foreseeable future.

The Complementary Basic Education Programme was funded by DFID and USAID and managed by the Management Unit at Crown Agents, in partnership with the Ghanaian Ministry of Education and Ghana Education Service. The evaluation data which is used in this blog was commissioned and funded by DFID, Ghana.

Dear authors,

Congratulations on the attempt to quantify learning loss as a result of absenteeism.

The interesting thing is the recovery. It would be good to have some data on recovery time vs absence. For instance, is there a time when recovery is not possible?. And can recovery onto the original learning trajectory be achieved?

It. Is also interesting that you chose to measure learning by response to numeracy problems. Do other skills follow a parallel course to numeracy? I doubt whether this could be demonstrated.

Dear David Wheeler

Thank you for your comment. Indeed, you raise important points. One point is about the measure of academic attainment. We use numeracy here, but we could also use literacy or other important skills also developed throughout education. We are currently extending the analysis to literacy and so far we found that the pattern is the same. Unfortunately, we do not have measures for other skills, for example communication skills, socialising, confidence, and other life skills, which are important and could be developed by the provision of complementary basic education. We are unsure how these skills are further developed in the interactions between the home and the school, and then the potential impact of school closures on these skills. Your second important point is about recovery time. Our research suggests that children who continue in education tend to have upward skills formation in these foundational numeracy skills. We are unsure, as you point out, whether there will be a point where these students may not be able to recover skills which previously were learned. I believe this is an issue of mastering skills and the point which you raise is: at which point students have mastered these foundational numeracy skills. From our research we only have some evidence which points in this direction. The learning loss for the most foundational numeracy skills, just learning to identify numbers, is greater than for addition and subtraction. What this implies is that at some point, these basic skills could remain in the children’s for a longer time, hence, the learning loss due to school closure could be larger in new skills, rather than for skills which have been already learned and understood.

We hope this helps. Thank you again for your interest in our research.