This blog was written by Tanushree Sarkar, a disabled woman and doctoral student in the Community Research and Action program at Peabody College, Vanderbilt University. She has a Master’s degree in Social and Cultural Psychology from the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her research examines the relationship between education policy and teacher practices for inclusive education in India. This article was originally published on the Cambridge Network for Disability and Education Research (CaNDER) website on 12 August 2020.

India’s National Education Policy 2020 (NEP) has been hailed as a new era in educational reform. However, it exists within a framework of pervasive policy gaps in the education of children with disabilities. Inclusive education in India has been described as exclusive of children with disabilities. Disabled children rarely progress beyond primary school, and only 9% complete secondary education. Around 45% of disabled people are illiterate and only 62.9% of disabled people between the ages of 3 and 35 have ever attended regular schools. Specific disability categories and genders are affected disproportionately. For instance, children with autism and cerebral palsy and girls with disabilities are least likely to be enrolled in schools. Disability is most likely to inhibit a child’s access to pre-school and primary education. Less than 40% of school buildings have ramps and around 17% of schools have accessible toilets. Although technology is a key focus of the NEP, only 59% of schools across the country have access to electricity.

The finalized policy incorporates several recommendations of disability organizations on the 2019 draft. The NEP asserts that children with disabilities will have opportunities for equal participation across the educational system. A major victory is the recognition of the 2016 Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (RPWD) and its provisions for inclusive education, defined as a system of education where students with and without disabilities learn together. These recommendations include non-discrimination in schools, accessible infrastructure, reasonable accommodations, individualized supports, use of Braille and Indian Sign language in teaching, and monitoring among others. The policy has provisions for recruitment of special educators with cross-disability training and incorporates disability awareness within teacher education.

The finalized policy incorporates several recommendations of disability organizations on the 2019 draft. The NEP asserts that children with disabilities will have opportunities for equal participation across the educational system. A major victory is the recognition of the 2016 Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (RPWD) and its provisions for inclusive education, defined as a system of education where students with and without disabilities learn together. These recommendations include non-discrimination in schools, accessible infrastructure, reasonable accommodations, individualized supports, use of Braille and Indian Sign language in teaching, and monitoring among others. The policy has provisions for recruitment of special educators with cross-disability training and incorporates disability awareness within teacher education.

In this piece, I examine the implications of the NEP for children with disabilities around four key aspects: (i) school choice, (ii) teacher and special educators, (iii) assessments and curricula, and (iv) terminology of inclusion and disability.

I. School choice – special, regular, or home-based education?

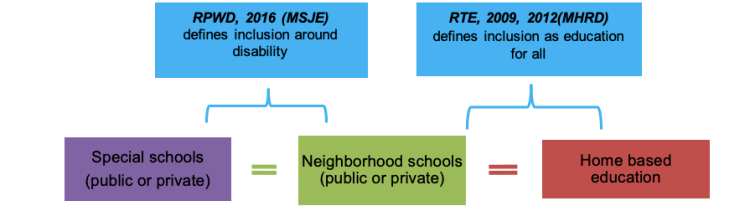

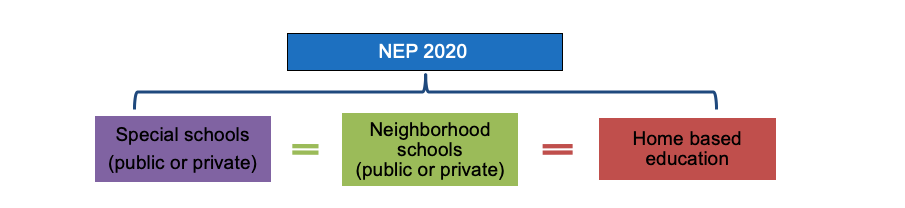

The lack of coherence between the 2009 Right to Education Act (RTE) and the RPWD on the educational options for children with disabilities has been highlighted as a major point of contention. The 2012 RTE amendment has provisions for children with disabilities to be enrolled in neighborhood schools and recognizes a separate category, children with severe disabilities, who can opt for home-based education. On the other hand, the RPWD recognizes the right of children with benchmark disabilities to enroll in either neighbourhood schools or special schools of their choice. Thus, while the RTE is silent on the issue of special schools, the RPWD does not offer guidance on home-based education (Fig 1). The NEP attempts to resolve this issue by clearly stating all three – neighborhood schools, special schools, and home-based education – as options for the education of children with disabilities, thereby attempting to resolve the ambiguities around school choice (Fig 2). However, there are several questions that remain.

- Status of home-based education

The NEP states that home-based education will be audited based on the norms in the RPWD. An audit of home-based education is essential as there are concerns about how children are identified to receive this provision and the quality of education provided to them. Block-level special educators have highlighted several challenges they faced in providing home-based education, including time and resource constraints, cultural norms and safety, and lack of clear curriculum and assessments.

However, the provisions on education in the RPWD focus on creating a system of inclusive education through accessible buildings and classrooms and individualized support towards full inclusion. It is unclear how these provisions apply in the context of home-based education, an educational option the RPWD does not endorse. Further, endorsing home-based education, instead of stating how schools and classrooms can be made accessible and inclusive for children with additional support needs, raises questions about whether the educational system views some children with disabilities unworthy of inclusion.

- Governance of special schools

In accordance with the RPWD, the NEP includes special schools as an option for children with benchmark disabilities. However, it is unclear whether the newly re-named Ministry of Education will regulate special schools as regular schools or whether they will continue to fall under the ambit of the Ministry of Social Justice and Welfare (MSJE). Not recognizing special schools as schools shortchanges children with disabilities – there are no clear guidelines around quality, curriculum, certification, or infrastructure. It reinforces the idea of parallel, segregated school systems for some instead of a common schooling system for all. These division further shifts “social inclusion towards a charitable model of social isolation”

The current mechanisms for regulating special schools often fall short as theRPWD has little power to enforce standards; only education authorities can derecognize schools for non-compliance. Thus, progressive provisions for children with disabilities in the NEP might not apply to special schools. For example, there is unlikely to be publicly available information about infrastructure, resources, and academic standards in special schools, all of which the NEP purports will build regular schools as “vibrant institutions of excellence.” The NEP also pushes for Indian Sign Language to be standardized as a language for teaching deaf children – however, without the Ministry of Education oversight of special schools, it is unclear whether this would apply to schools for deaf children, which often emphasize lip-reading and speech therapy over teaching sign language. At the same time, the place of special schools within the policy framework that argues for inclusive education continues to be tenuous.

- Introduction of the school complex

The NEP complicates the idea of school choice for children with disabilities by introducing school complexes and school rationalization policies. In this plan, schools within a 5-10-kilometer radius will be consolidated within one school complex. The document states that this will help ensure there are adequate resources for children with disabilities including resource centers and special educators. This seeks to solve a key problem for children with disabilities – there is a grave shortage of special educators. Block-level special educators often are required to cover children across 150 schools and travel long distances to make sure all children with disabilities are catered to in their blocks.

However, for parents, school distance is an important consideration for school choice. Parents of children with disabilities have safety concerns with transportation; in some cities, mothers often attend schools with their children to ensure safety and well-being – usually paying for the expenses on their own. While the RPWD provides for transportation for children with high support needs and their attendants, data indicates that transportation allowance or services are often not dispensed. Thus, there is a real danger that school complexes, in their intention to rationalize resources and ensure greater individualized resources and support may inadvertently lower attendance and enrolment of children with disabilities. Another concern with school complexes and resource centers within them is that they might lead to segregation, with children with disabilities taken out of regular classrooms during school hours or entirely excluded.

II. Teachers and special educators

The NEP addresses several aspects of teacher education, preparation, and service conditions that are relevant for children with disabilities. These include short-term specialization courses to teach children with disabilities and modules on teaching children with disabilities within existing programs. Moreover, teachers will be provided greater autonomy in selecting pedagogical tools relevant to their classroom contexts and will no longer be required to perform non-teaching tasks. Teachers will be trained to recognize and identify disabilities, particularly specific learning disabilities. Non-teaching responsibilities and teacher shortages often prevent teachers from fulfilling teaching responsibilities towards children without disabilities such that children with disabilities appear to be a burden and a distraction in the classroom.

The importance of these policies cannot be understated. Several studies have documented teacher challenges and concerns in teaching inclusive classrooms –teachers in India do not rate themselves competent to be inclusive and do not have adequate training, infrastructure, institutional or peer support for inclusive education. Teachers are often unaware of policy provisions around inclusive education, and struggle to translate inclusive education policy into classroom practice. However, the success of the policy is contingent on the availability of teacher educators.

The importance of these policies cannot be understated. Several studies have documented teacher challenges and concerns in teaching inclusive classrooms –teachers in India do not rate themselves competent to be inclusive and do not have adequate training, infrastructure, institutional or peer support for inclusive education. Teachers are often unaware of policy provisions around inclusive education, and struggle to translate inclusive education policy into classroom practice. However, the success of the policy is contingent on the availability of teacher educators.

The policy does not prescribe regularizing special educators as teachers, but views special education as a specialization for general teachers. Government special educators face incredible challenges – they are often hired in contract positions, have low pay, and endure working conditions that they describe as hostile and exploitative. An important policy consideration is the proposal for greater consonance between the NCTE and the RCI to ensure that special educators have both content and pedagogical knowledge, a gap that both teachers and special educators have identified.

III. Standardized assessments, curricula, and target-based reforms:

The NEP emphasizes achievement of foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN) for all children by grade 3 – setting up a national mission to reach this target by 2025. The push towards a national mission for FLN comes after several years of findings from the Annual Survey of Education Report (ASER), which has consistently found that children across the country are unable to read grade-level texts. These findings were echoed by the National Achievement Survey (NAS) 2017 conducted by the state-run National Council for Education Research and Training (NCERT). The NEP describes a growing learning crisis, wherein children are enrolled in schools but have not attained foundational literacy or numeracy.

However, ASER does not collect data from children with disabilities, citing time and resource constraints. While the NAS collected disability data, it does not report this data in the State Report Cards. Additionally, there are several issues in the way children are identified – usually leading to under-reporting of disability. Identification of children with disabilities is a major challenge for teachers. The NEP only refers to learning disabilities in the context of training teachers to identify disabilities, ignoring other cognitive disabilities in the RPWD such as intellectual disabilities and autism.

The policy states that curricular changes will be made in consultation with national institutes under the Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities. This is a positive step if it ensures that issues of accessibility and inclusion are not viewed as problems to solve for after the core has been designed, such that disabled children need to adjust or fit to a system not designed for them. Instead, the curriculum is designed to be flexible, considers individual differences as strengths, and offers multiple means of engagement, assessments, and representation of knowledge.

The NEP emphasizes accountability standards based on learning outcomes over inputs. This includes tracking learning outcomes as part of a National Assessment Center known as PARAKH, which means to test or evaluate, where students will be assessed at grades 3, 5, and 8. Examinations for grade 3 will be crucial in determining the success of the mission towards foundational literacy and numeracy. PARAKH will also be a part of school accountability and standards, such that all schools will make their assessment data publicly available. Until PARAKH is established, this will be done through the existing NAS. The policy states that PARAKH will ensure accessible assessment guidelines for children with learning disabilities. This further marginalizes children with intellectual disabilities and other cognitive disabilities, who do not find a place in the NEP. It is also unclear how the National Testing Agency (NTA), that will conduct aptitude tests for college admissions and pre-service teacher education, will be made accessible to children with different disabilities.

There is perhaps a real danger that children unable to achieve FLN by grade 3 may be labelled as learning disabled and/or placed in special education. Scholars have highlighted tensions between achievement and inclusion as a result of the greater push for market-based standards and accountability reforms. They argue that such testing regimes, in their effort to raise academic standards, end up perpetuating inequities between children who are viewed as academically successful and those who are not.

IV. Terminological confusion and real-world implications

By following the RPWD definition of inclusive education, the NEP takes a clear stand in the confusion between inclusive education as a social justice, education for all agenda as in the RTE or as an educational system where children with and without disabilities learn together as per the RPWD (Fig 1) . However, the NEP misses the opportunity to move past the decades old confusion in the Indian educational system between ‘inclusion’ and ‘integration’.

Education policies in India have historically adopted the term inclusion or use integration interchangeably with inclusion without recognizing key differences between these two approaches and continuing practices that require disabled children to adjust and fit within the system (integration) rather than transforming core practices that are designed to cater to the upper caste, upper class, rich, urban, able-bodied male to be truly equitable and inclusive. However, the NEP is replete with the synonymous use of inclusion, integration, mitigation, and rehabilitation and the terms disability, divyang[1], children with special needs, and differently abled. This is not just an issue of word choice but indicates a broader incoherence around disability-inclusion within the Indian educational system.

The NEP conflates these distinct ways of thinking about the education of children with disabilities. At one end, the policy views disability as an individual problem to be solved through ‘rehabilitation’, ‘mitigation’ to ensure that children with disabilities ‘integrate more easily’. On the other hand, it endorses the idea of creating an educational system that is designed for children with and without disabilities to be in the same classroom, addresses barrier-free access, and puts forth a plan for the inclusion of children with disabilities in the curriculum and assessment. These seem like add-on, retrofitted solutions for the ‘problem of disability’ instead of a critical examination of existing practices and how they perpetuate ableism. The policy therefore further undermines the notion of inclusive education, which views the challenges of disabled people as a result of structural constraints, not individual shortcomings that need to be fixed.

The NEP conflates these distinct ways of thinking about the education of children with disabilities. At one end, the policy views disability as an individual problem to be solved through ‘rehabilitation’, ‘mitigation’ to ensure that children with disabilities ‘integrate more easily’. On the other hand, it endorses the idea of creating an educational system that is designed for children with and without disabilities to be in the same classroom, addresses barrier-free access, and puts forth a plan for the inclusion of children with disabilities in the curriculum and assessment. These seem like add-on, retrofitted solutions for the ‘problem of disability’ instead of a critical examination of existing practices and how they perpetuate ableism. The policy therefore further undermines the notion of inclusive education, which views the challenges of disabled people as a result of structural constraints, not individual shortcomings that need to be fixed.

Children with disabilities in the policy are primarily viewed as recipients of welfare and care in the form of peer tutoring, open schooling, and one-on-one teaching. There is a need to go further, to recognize disability as an identity and as a form of diversity rather than solely a deficit – an example of this would have been to suggest the standardization of Indian Sign Language as a valuable language system for all students, not just for ‘students with hearing impairments.’ That is, the educational challenges of children with disabilities stem from a rigid curriculum, inaccessible schools and classrooms, absence of modified assessments, and deficit perspectives that place limits on what disabled children can achieve.

India ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) in 2007, which envisions free, quality, inclusive education as the fundamental human right of every child with a disability. In line with the UNCRPD, there is a need to ensure that the NEP leads to renewed efforts towards greater budgetary allocation, a systems approach with co-ordination across government departments, ending segregation of disabled children, and a focus on sustainable transitions to higher-education and employment.

Images in this piece are from the author’s fieldwork in India.

[1] Divine-bodied; the term replaced the previously used viklang in 2016, a move critiqued by disability activists and scholars

It always good to highlight and ultimately guide us for further introspection of NEP

Thank you so much for this information. I want to do research on a topic of provisions for Inclusive education in NEP 2020.

Thank you very much.

Tanushree Sarkar’s insightful blog sheds light on the intersection of education policy and teacher practices for inclusive education in India. Her perspective, shaped by her experiences as a disabled woman and her academic journey, adds a unique dimension to the discourse. The commitment to inclusive education resonates with the values upheld by the best schools in vijayanagar These schools, by championing inclusivity, contribute to fostering environments where diversity is celebrated, echoing the very essence of Tanushree’s research and advocacy.

thanks

I was wondering if i can interview Tibetan disabled students and you

i am trying to connect disability studies with Buddhism

thanks

Anita

Great insights! It’s crucial that the NEP includes robust programs for disabled adults to ensure lifelong learning opportunities. Inclusive education must extend beyond schools to support all stages of life.

Thank you for sharing! Access to programs for disabled adults is crucial for fostering inclusion and empowerment. Whether it’s education, job training, or social support, these programs can make a significant impact. Let’s continue advocating for greater accessibility and opportunities!