This article was written by Oby Bridget Azubuike and Bisayo Aina from The Education Partnership Centre, Lagos. For more information on the survey and full report please visit www.tepcentre.com

“I Can’t Support My Child’s Learning Because I Am Not A Teacher.”

Following the outbreak of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic across the world, many nations experienced a shutdown of their economies which affected different sectors and industries on a global pedestal. The Nigerian education sector was not exempted from this. Schools were closed and remote teaching and learning began for many children. Virtual learning interventions and solutions were rolled out, pioneered by both private and public stakeholders in the education sector to support the continuation of learning and prevent a learning slide. Parents were faced with the new challenge of being both parents and teachers at the same time.

Between April and May 2020, The Education Partnership (TEP) Centre, through an online survey, set out to understand how parents and students were adapting to this new reality of remote schooling. The main aim of the survey was to identify and map education interventions that were being implemented in Nigeria during the COVID-19 pandemic and how the recipients of these interventions were fairing. Parents were considered an integral part of this survey due to their direct contact with learners. Their role as guardians and providers for learners under their care, positions them to share insights on the adaptation of learning. Our survey captured responses from 626 parents across 30 states in Nigeria. The average age of the parents in our sample is 40 years. 83% of the parents in our sample have attained post-secondary education. We use the data from this online survey to shed light on how parents are supporting their children’s learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria.

The Role of Parents in Education

Parents have been known to be a child’s first teacher from the moment a child is born and as they mature into adults, the traditional role of parents involve teaching, guiding, and raising children to become strong standing members of their communities. As children begin formal schooling, most parents allow the school to take on a major part of their formal education. Where formal education is concerned, parents are more of providers. Ensuring that children have the needed provision and support to access education and learning, except in cases where parents have taken the full responsibility of home-schooling their children (Benjamin, 1993; Ceka & Murati, 2016; Emerson et al., 2012). Since the pandemic started, parents are now taking on a more support-oriented role by supporting their children as they take on assignments and home projects.

According to Hoover-Dempsey et al (2005), the factors that influence a parent’s ability to actively contribute to a child’s education are influenced by four constructs:

- the parental role construction which is shaped by the beliefs, perception and experiences of the parent;

- the invitation of parents by the teachers and schools to be active participants in the education of their children;

- the socioeconomic status of the parent which influences the skill, knowledge, energy and time availability of the parent;

- and the self-efficacy and confidence derived by the parent from being an active participant.

Research has shown that parental involvement in their child’s education improves their educational achievements from early childhood; it causes them to stay longer in school and encourages an overall positive development in the child (Mapp and Handerson, 2002).

Parents Supporting Children’s Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Nigeria

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the subsequent closure of schools, it became apparent that parents had to assume the full-time role of educating their children and support their learning virtually. In our online survey, we asked whether parents were helping their children learn during the pandemic and only 83% of the parents in our survey affirmed that they were actively helping their children learn during the pandemic. When we asked parents not supporting their children why that was the case, the majority reported that they did not know how to because they were not teachers. Other reasons cited were that parents were too busy at the time or could not afford the cost of supporting their child’s learning.

We went further to analyse the data by educational background of parents. We found that parents who said they did not know how to support their children’s learning remotely were more likely to be parents who had attained secondary education or lower. The parents who reported being too busy to support their children’s remote learning during the pandemic were more likely to be parents with post-secondary education. The differences between these two groups were also statistically significant. These findings provide evidence not just that some children may have been missing out on learning during the pandemic but that the reason for their exclusion from learning varies along the lines of their parents’ education.

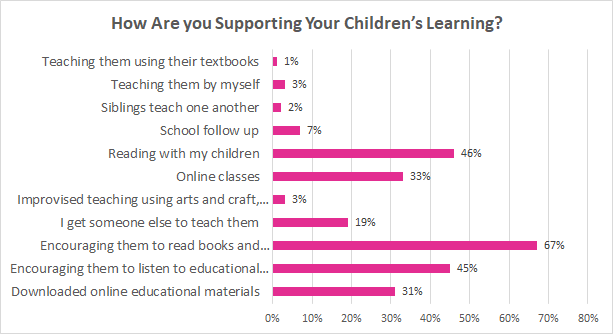

For parents whose children have been actively learning, we asked how they were supporting their children’s learning during the pandemic and 67% reported that they both encourage them to read books and participate in online classes. 46% reported that they read with them, and 19% of the respondents got someone else to teach their children.

Majority of the parents in our survey are supporting their children’s learning through various means, as reported in Figure 1 above. However, this has not been without its own challenges and drawbacks. Parents with younger children are more likely to be involved in teaching them, while older children are more likely to pursue independent learning. Overall, parents reported that their children were adopting virtual learning platforms that ranged from low-tech platforms, such as radio and television, to high-tech platforms such as online classes and virtual conferencing.

Parents reported that they explored different learning solutions for their children, both traditional and modern methods as well as tools. We asked parents to rate the effectiveness of the learning platforms their children were adopting during the pandemic, their ratings ranged from “very poor” to “very good”. Parents reported that the virtual learning platforms were challenging because of the high cost of internet data and for parents who reported that their children were using radio and television learning programmes, the major challenge was with electricity supply and the lack of feedback and personalisation of the learning content. Parents that gave positive ratings to the learning platforms cited the development of digital skills and continuing academic engagement for their children.

Our findings reveal that one of the main challenges faced by parents in teaching their children remotely is the lack of financial resources to adequately provide remote learning tools. The high costs of internet data, alternative power supply and internet-enabled devices were cited as some of the barriers to learning remotely. One parent in particular, reported that virtual learning was not effective for her child and when we asked why, her response was:

There’s no money to keep buying airtime; and for the television programmes, there is no power supply.

This is an indication that socio-economic status is a major factor affecting how children are learning remotely during the pandemic. Another parent reported the reason for rating the effectiveness of virtual learning as poor was because:

The system is alien to them, and they are easily distracted at home. Network, power and non-availability of laptops for the classes…

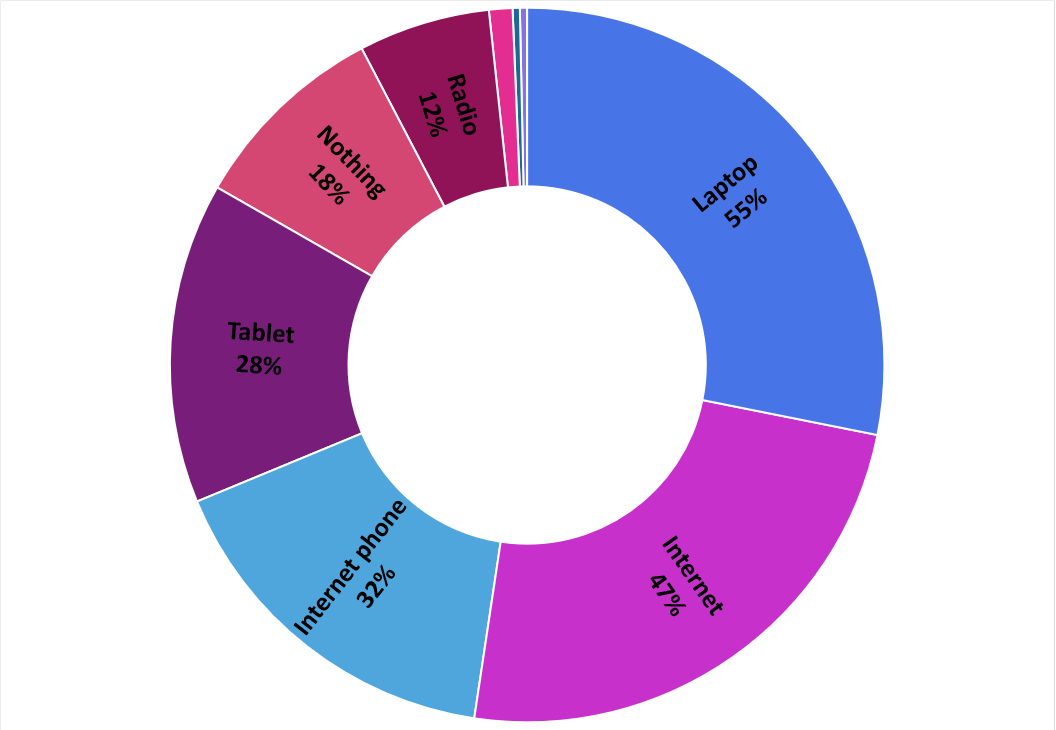

Where parents are able to provide the tools and the enabling environment for their children to learn, then learning can happen seamlessly, but this is not the case for all parents. We asked parents what their children needed to aid remote learning, 55% said their children needed laptops, 47% reported internet access, 32% and 28% cited internet-enabled devices; phones and tablets respectively.

Only 18% of the parents said their children had all they needed to continue learning remotely. The parents who said their children needed nothing to learn remotely, were also more likely to give their current remote learning platform a “good” or “very good” rating on the effectiveness of the remote learning platform their children were utilising. One parent with a master’s degree and with children attending private schools reported that her children’s school taught them remotely through Google Classrooms and Edmodo.

The older kids are very engaged and relished the opportunity to connect with their teachers and classmates. The assignments were easily accessed and completed and were graded immediately. They watched videos and answered questions. The only downsides were the amount of data used and the sometimes dodgy connection quality.

Other parents within the survey who gave positive ratings on the effectiveness of the remote learning platforms cited their children’s prior exposure to such platforms ensured a smooth transition for them during the pandemic, which implies that the tools for remote learning were previously accessible to their children.

In Summary

The implications of our findings point to unequal access to education for children. The inequality of access to education, although not a new phenomenon, is likely to be further exacerbated as schools remain closed. Our findings have pointed to challenges parents are facing in their ability to assume responsibility as teachers for their children. Their knowledge, educational background and socioeconomic status all play a role in whether their children learn remotely and to what extent they can adapt to virtual learning. Unequal access to remote learning opportunities will result in inequality of educational outcomes of children. Where children with wealthier parents may have more advantages than their counterparts in poorer households with less educated parents or parents who are too busy. We asked parents what the government could do to support them during the pandemic, and their requests broadly covered palliative measures to help them support their children’s learning as schools remain closed. Specific requests for financial support, stable electricity supply and internet access were highlighted. Requests for pedagogical support for children and other interventions to ensure children continue to learn remotely were also highlighted.

There is a need for education stakeholders to ensure learning for all children in Nigeria and that no child is left behind, targeted support may be required for different groups of children, from financial to infrastructural to alternative remote learning options. More research is needed to assess how much learning has taken place during the period of the pandemic and where there are gaps, remedial programmes will need to be implemented. These measures are important to ensure that the disadvantages faced by children unable to learn effectively during the COVID-19 pandemic are not carried on to the rest of their education and life outcomes.

References

Benjamin, L. (1993). Parents’ Literacy and Their Children’s Success in School: Recent Research, Promising Practices, and Research Implications. Education Research Report.

Ceka, A., & Murati, R. (2016). The Role of Parents in the Education of Children. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(5), 61-64.

Emerson, L., Fear, J., Fox, S., & Sanders, E. (2012). Parental engagement in learning and schooling: Lessons from research. A report by the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) for the Family–School and Community Partnerships Bureau: Canberra.

Henderson, A. T., & Mapp, K. L. (2002). A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of School, Family, and Community Connections on Student Achievement. Annual Synthesis, 2002.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Walker, J. M., Sandler, H. M., Whetsel, D., Green, C. L., Wilkins, A. S., & Closson, K. (2005). Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. The elementary school journal, 106(2), 105-130.

For more information on the survey and full report please visit www.tepcentre.com