This blog was written by Guy Le Fanu, Global Technical Lead for Education at Sightsavers and was originally published on the Devex website on 28 July 2020.

The world is experiencing one of the biggest disruptions in the history of education, with more than 1 billion children prevented from getting the education they need due to the coronavirus. Marginalized groups are particularly affected. According to the World Bank, children with disabilities, especially girls, are the most excluded from education all over the world and this risk is even higher during crises.

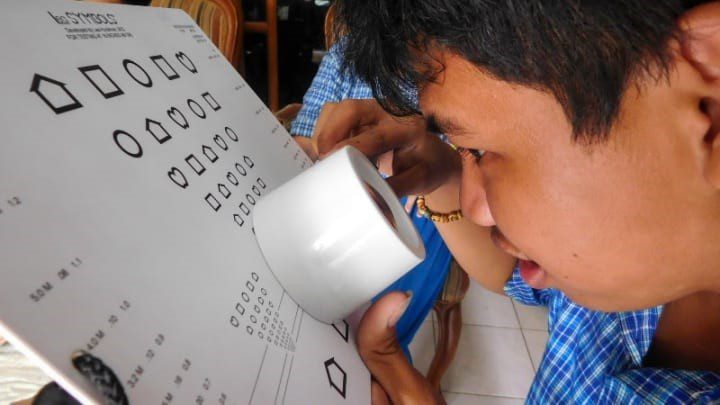

A child with a hearing impairment undergoes a low vision assessment in Cambodia. Photo by: © CBM / CC BY-NC

Without immediate support both during and following school lockdowns, many children with disabilities may miss out entirely or never return to school.

Countries are providing distance learning, but often this is not suitable for students with disabilities or from poorer households and they are still being left behind. It is essential for NGOs working in inclusive development and education to work with governments and communities around the world to reach these children during school closures.

With closures now being extended in many countries, and more money being allocated to distance education through the crisis, we have five key recommendations — based on Sightsavers’ own internal program reporting — on how to reach children with disabilities during lockdowns and ensure they have equal access to education.

1. Support learning from home

How do you follow a radio lesson if you are deaf? Or what if your family does not own a smartphone?

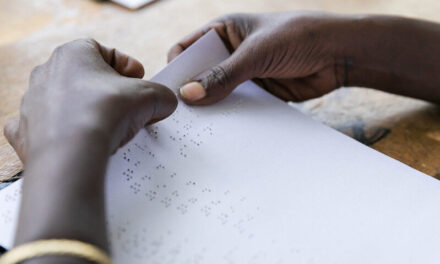

Distance learning, or studying from home, needs to be designed with accessibility considerations in mind. This can range from adding sign language or subtitles to TV lectures, to providing technology that is compatible with screen readers or braille and plain language versions of texts. If assistive devices are needed by children to support their learning at home, training may also be required.

In India, for example, we have provided accessible telephone training for over 200 children to use laptops, mobile phones, and tablets distributed to them. In Sierra Leone, People’s Postcode Lottery funding has been helping to distribute radios and batteries to children so they can take part in the government’s radio education programs.

In Senegal and Cameroon, schoolteachers have been using Whatsapp messages to contact children. They have described the service as indispensable in supporting inclusion and continuing to deliver teaching to those without access to other forms of distance learning.

2. Get parents involved as educators

Children need support to learn, and while they’re at home the involvement of caregivers is key. Parents need concrete guidelines so they can help their children.

Information is vital, so we have been distributing guides, leaflets, and providing lesson support by phone, tailored to each child’s disability or special needs.

In Senegal, Saturday is designated for speaking to parents, and phone calls are set up for parents and teachers to chat about progress and problems. In Cameroon and Sierra Leone, trained “inclusion champions” use Whatsapp to coach parents in their local languages on how to support their children’s progress.

With the right support, parents can be positively involved in their children’s learning.

3. Help teachers adapt to distance teaching

Teachers need training in distance teaching in addition to reviewing the progress of children with disabilities. This support can be offered over-the-phone or through online hubs for teachers to exchange information and support each other. Funds can be allocated to supply teachers with the necessary technology, such as smartphones, if they do not already have it.

4. Support with COVID-19 prevention

Many people with disabilities or from poorer households are missing out on resources and information about protecting themselves from COVID-19. Official messaging is either inaccessible — not translated or adapted for people with disabilities — or unaffordable.

Interventions can be as simple as purchasing and distributing hygiene kits or delivering accessible information to families in person or via Whatsapp. If they do not have access to COVID-19 prevention advice, their well-being and ability to participate in education will suffer. In Cameroon, where some children have gone back to school for exams, we have also provided funding for cleaning buildings so spaces are safe.

5. Work with disabled people’s organizations and community groups

It is imperative that disabled people’s organizations and parents of children with disabilities are involved in education planning. They have the expertise and know the most about their communities and their needs.

And advocacy works. In Pakistan, for example, advocacy work with local partners has resulted in people with disabilities being added to the list of vulnerable households who receive government support.

From raising awareness to knowing the logistics of local contexts — and because it is their own lived experience — disabled people’s organizations and community groups are the best placed to help design and run inclusive education programs.