This blog was written by Asma Zubairi, PhD student, and Pauline Rose, Director of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge. It was originally published on the Global Partnership for Education website on 18 November and on the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) website on 19 November 2020.

Since its establishment 20 years ago, the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) has grown from a small group of professionals working in a context where education in emergencies was hardly recognised, to a firmly established field involving a huge global network. To recognise the achievements of the network on its 20th anniversary, INEE has just published a flagship report written in collaboration with the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge.

Since its establishment 20 years ago, the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) has grown from a small group of professionals working in a context where education in emergencies was hardly recognised, to a firmly established field involving a huge global network. To recognise the achievements of the network on its 20th anniversary, INEE has just published a flagship report written in collaboration with the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge.

Alongside the many positive developments in relation to the ever-increasing visibility of education in emergencies, the report presents sobering findings on trends in humanitarian aid to education. INEE and its partners have highlighted the huge neglect of education in humanitarian responses. In doing so, their advocacy has been key to identifying the importance of viewing education as ‘life-saving’, alongside other sectors, such as food security, health care and shelter. This is both in recognition of the premium that children, young people and parents place on education in emergency situations, as well as ensuring that education can provide a solid basis for post-conflict and disaster reconstruction, alongside initiatives from other sectors.

Between 2000 and 2020, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) launched a total of 598 appeals to assist populations affected by conflict, disaster, or a protracted crisis. Of these appeals, 502 included requests for education, with only 423 of these receiving funding. As we identify in the report, the amount of funding available to education in humanitarian situations remains woefully below the amount needed.

Despite ongoing advocacy, education continues to remain far behind other sectors, raising questions of whether the humanitarian field has yet to recognise it as life-saving.

A promising sign is the establishment of Education Cannot Wait (ECW) in 2016, as part of an effort to reposition education as a priority sector within the humanitarian aid architecture and to provide dedicated financing to education in crisis-affected contexts. Positively, over the past 20 years there has been increased attention of development funding to education in countries affected by crises, for example through the Global Partnership for Education (GPE). By December 2019, two thirds of all GPE grants were reported to be allocated to countries affected by fragility and conflict.

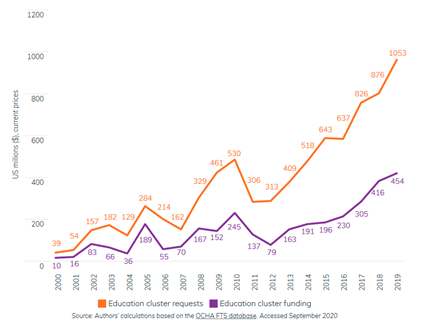

Despite increased humanitarian funding for education, a large share of requests still go unfunded

There is some good news – humanitarian aid to education has increased substantially over the last two decades, with an upward trend particularly noticeable since the establishment of ECW in 2016. In the light of the protracted nature of crises and the severity and frequency of environmental and other emergencies, requests for education aid increased 27-fold from 2000 to 2019, from US$39 million to just over US$1 billion (see Figure 1). However, the amount of funding received for education remains only around half of the amount that is requested each year.

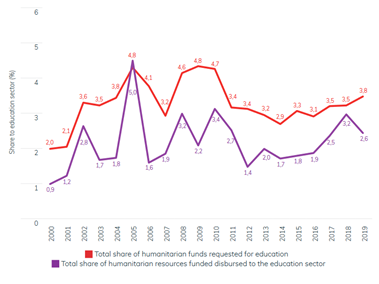

Education is still a low priority in humanitarian responses

Humanitarian spending on education continues to lag far behind other sectors. While the share of humanitarian funding to education increased from a low of just 0.9 percent in 2000, by 2018 education still received just 3.2 percent of total humanitarian spending, falling again to just 2.6 percent in 2019 (see Figure 2). This is despite calls for a modest target of increasing education funding to 4% of humanitarian funding, set by the United Nations in 2012. As such, the report calls for this modest target of 4% to be met with urgency and, ideally, for an increase to the 10% target that the European Union has set itself.

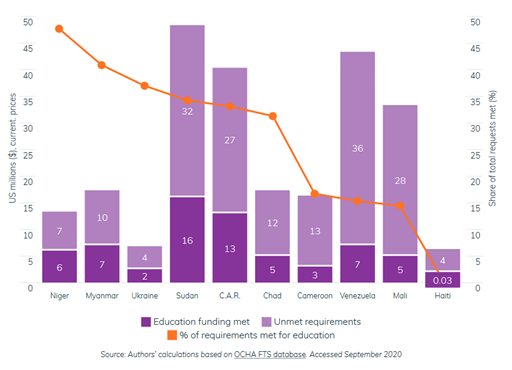

Countries most in need are being left behind

Despite the upward trajectory in education funding since 2016, there is a concern for the continued skewed nature of this funding. Of the 423 humanitarian appeals for the education sector which received some funding, half of all funding went to just 29 appeals. Funding for the Syrian crisis, which started in 2011, appears to have benefited in particular from the increase in humanitarian funding. Meanwhile funding for more protracted (and less visible) crises, such as some of those in sub-Saharan Africa, remains neglected. Although there is a desperate need for funding in the more ‘publicised’ conflict-affected settings, there is an urgent need to address the funding gap for the protracted ‘forgotten’ crises that do not receive the same media attention.

In 2016, UNICEF estimated that nearly 75 percent of children living in countries affected by conflict or disaster were in sub-Saharan Africa; 12 percent resided in the Middle East and North Africa region. By comparison, in 2019, the share of total humanitarian aid spent on education to sub-Saharan Africa was 37 percent, compared to 38 percent in the Middle East and North Africa. Moreover, of the 293 education appeals which have been launched for countries in sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2020, 51 have been totally un-funded.

Figure 3: Ten of the eleven ‘forgotten crises’ that issued an education appeal had less than 50 percent of their requests funded in 2019

Education is extremely poorly funded during the COVID-19 pandemic

In August 2020, the United Nations indicated that the pre-COVID-19 education funding gap in low- and lower-middle-income countries could increase by as much as 30 percent from the current US$148 billion. With domestic revenues projected to contract due to the global economic downturn caused by the pandemic, and with development aid under increasing strain, the funding crisis for education is at a critical juncture. Of the 59 countries that the UN identified as most in need of humanitarian aid due to the pandemic, 55 had already issued humanitarian appeals due to ongoing crises.

The COVID-19 funding appeals across all sectors from all countries totalled US$10.3 billion, of which just over a quarter (US$2.7 billion) had been funded by September 2020. Requests for education funding were made by 34 countries, but a mere 5 percent of funding requests were met by this time.

This percentage to education is far lower than for appeals overall, which suggests that education is again lagging behind other sectors in humanitarian funding. Yet, the pandemic is having a huge impact on children’s lives through school closures, with related effects on both their learning as well as mental health and well-being overall. Now more than ever, it is vital that education is recognised by the international community as life-saving.

While there is much to celebrate in terms of education in emergencies being firmly on the map in the global agenda, including now visibly part of the Sustainable Development Goals, these trends in humanitarian financing highlight that there is no room for complacency. The role of INEE is as vital today as it was 20 years ago.