This article was written by Anne M. Hayes, Founder and Chief Operating Officer, and Hayley Niad, Program Manager and Researcher, International Development Partners, and Jennae Bulat, Senior Director of Teaching & Learning, RTI International. This blog was originally posted by International Development Partners on 24 April and then RTI ShareEd on 30 April.

All children have the right to learn.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the majority of education systems globally, impacting an estimated 91% of the world’s student population (UNESCO, 2020). Until more information is known about the virus and how to safely return to traditional school-based learning, countries are seeking ways to provide learning so that children and youth still benefit from education while at home. Unfortunately, during times of crisis, people who are the most marginalized risk being omitted from emergency response programming. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this is the case with some countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, as some seek ways to meet the educational needs of “normal” children before they address the education of children with disabilities. Establishing a learner hierarchy not only goes against the principles of education for all, but is counterproductive and squanders the opportunity to diversify and strengthen learning in a way that benefits all children. Now is not the time to become exclusionary in our approach to education; rather, it is an opportune time to promote diversified learning.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the majority of education systems globally, impacting an estimated 91% of the world’s student population (UNESCO, 2020). Until more information is known about the virus and how to safely return to traditional school-based learning, countries are seeking ways to provide learning so that children and youth still benefit from education while at home. Unfortunately, during times of crisis, people who are the most marginalized risk being omitted from emergency response programming. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this is the case with some countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, as some seek ways to meet the educational needs of “normal” children before they address the education of children with disabilities. Establishing a learner hierarchy not only goes against the principles of education for all, but is counterproductive and squanders the opportunity to diversify and strengthen learning in a way that benefits all children. Now is not the time to become exclusionary in our approach to education; rather, it is an opportune time to promote diversified learning.

Everyone learns differently (VARK, 2019). Providing instruction that only supports the most common types of learning needs obstructs the learning of children who are already overlooked and prevents the system from evolving. During this period of global school closures, as educational systems move from traditional learning to alternative learning options, such as online learning, radio, and television, the need to diversify learning formats is even more important and the opportunities for doing so are even more immediate.

If there was ever a time to be inclusive of learning, it is now. Fortunately, building, or rebuilding, instructional methods to be inclusive of all children, including children with disabilities; it is an attainable goal in all countries. Below, we provide practical suggestions on how governments, donors, and civil society organizations can support inclusive alternative education during COVID-19.

Use the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) in all alternative learning efforts.

Regardless of the type of alternative learning a country adopts to enable continued learning during school closures, all online, televised, and radio programming can be developed to incorporate the UDL principles. Even if learning can only be delivered via uni-dimensional (e.g., radio) or static asynchronous (e.g., worksheets or workbooks) channels, home exercises can be designed to encourage children to practice and apply information in different ways. For example, instead of asking children to only be passive listeners and do worksheets, they can be encouraged to act out new concepts or draw pictures to express understanding. Music that relate to the curriculum, such as songs that incorporate the target letter sound being studied, can help with student engagement. Information shared through radio, television, or the Internet can also give an overview of the learning session, state objectives, and use first-then methods (for example, “first we will learn the sound of a letter and then find things in your home that start with that sound.”). Such lesson scaffolding serves as a useful strategy for supporting learner engagement.

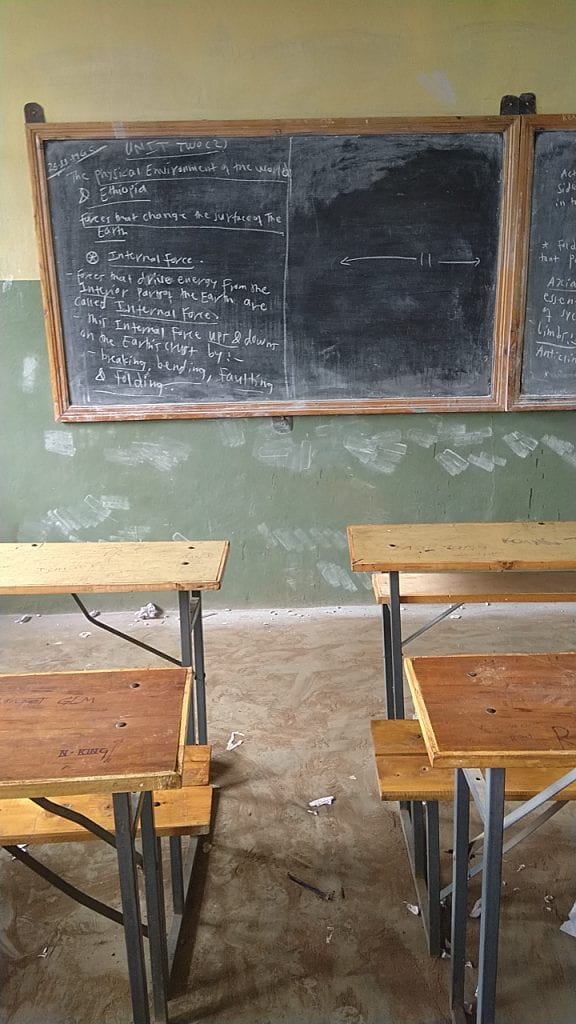

Promote the use of local household materials to reinforce learning.

Local materials in communities and homes with few resources can be crucial assets when promoting continuous education at home for children with and without disabilities. Suggestions for ways children can use household materials during remote learning include the following:

- Children can practice phonological awareness by identifying the initial sounds in the names of common household objects. This game requires no print literacy or supplementary materials and can engage both children and their parents.

- Beans, stones, or grains of rice can be used to form the shapes of letters, syllables, or words and can be used in various games and activities.

- Children can practice making letter shapes with their bodies or drawing the shape of a letter on another person’s back or hand, while the other person guesses the letter.

- Numeracy can be reinforced through adding and subtracting leaves, bottle caps, or stones. Children assisting families with farming or other household activities can be encouraged to count aloud the number of seeds planted, use subtraction to identify how many vegetables remain on a plant after harvesting, and pose other word problems that involve practical mathematics operations.

- Children who express themselves in different ways can be encouraged to draw simple icons on woven sacks, on spare paper, or even in the dirt and point to an image as a way to communicate at home.

Engage parents, caregivers, and siblings to support younger children and those who may be struggling to learn.

Parents and caregivers have always been an important part of education. With the shifts in education due to the COVID-19 pandemic, their role is even more critical. It is important to find simple ways for parents to be a part of the education process while ensuring they are not overburdened. Alternative learning platforms can make simple suggestions for how parents can reinforce learning while remaining safe at home. For example, when cooking, parents can count ingredients with their children to help them learn math skills or identify two household ingredients that start with the same initial sound. Peer learning and support is also an effective component of inclusive education. Siblings who have some literacy can help those who are still learning to practice writing letters. Siblings can also read aloud or tell each other stories, ask comprehension questions, or practice together adding and subtracting household items.

Ensure that all online content is accessible (i.e., sign language, closed captioning, and accessible PDFs).

Online learning can be an effective medium for education. However, if not done inclusively it can create additional barriers for children with disabilities learning. UNICEF has provided initial guidance on how remote online learning can be inclusive of persons with disabilities. Suggestions from UNICEF (2020a) include the following:

Glossary:

- Include a glossary for any new or difficult words/concepts in your materials.

- Glossaries should represent concepts or ideas through multiple methods, including images, videos, sign language, short and long descriptions, and related ideas.

- Link to the glossary directly from where words or concepts are introduced on a page.

Allow multiple methods of action or expression:

- When asking children to answer questions and express what they know, consider that children may prefer, or even require, using different modes of responding. Children should be encouraged to respond in ways they feel most comfortable. For example, modes of response include touch, type, multiple choice, memory, and recording video or audio responses.

- Activities that rely on a single sense, like asking a child what he/she can see around them, can exclude persons with disabilities. Online learning platforms should ensure that activities are available using multiple modalities so that all children can participate.

Use multiple methods or representation:

- Content can be presented in many ways. Where possible, use multiple media types, such as images, text, videos, audio, highlighted text, and iconography.

- To communicate complex or multi-step activity concepts, break the content into smaller, more digestible chunks, as needed.

- Consider using simple language or offer a simple language alternative. Consider that not all children may have acquired the vocabulary or understand the concepts or tasks being presented.

Make content engaging and stimulating:

- Use intuitive and engaging design for visual learners.

- Present activities and exercises using interactivity and/or games to engage children who prefer a kinesthetic approach.

- Where possible, include audio, such as voice-overs or sound effects.

- Break activities into step-by-step bits of information for easier comprehension.

- Include feedback to encourage and guide children.

More information on digital inclusive formats can be found on the UNICEF website.

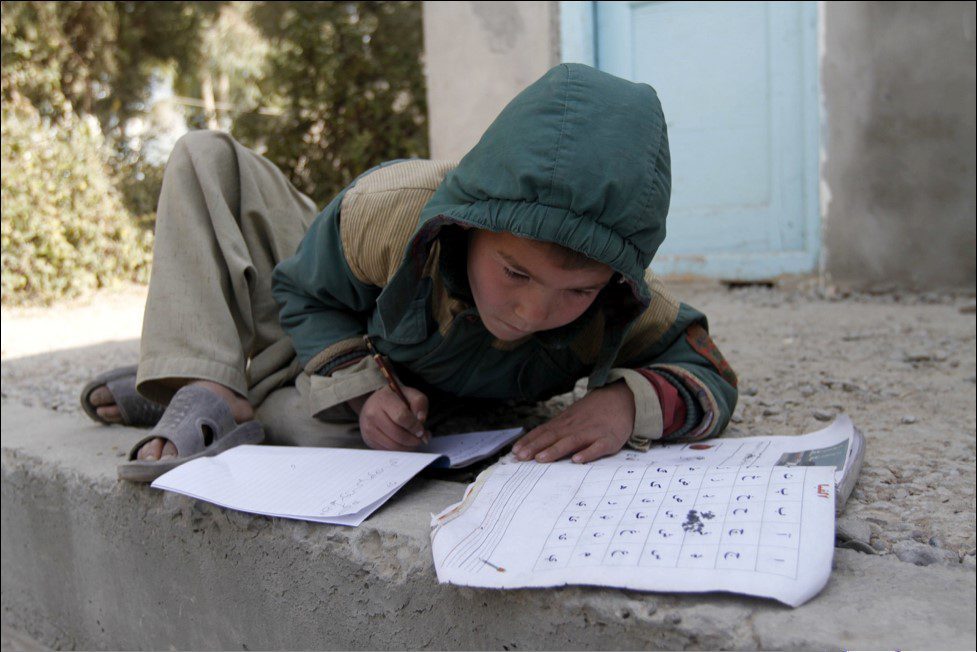

Recognize that alternative education efforts will benefit those children who may not have been in school prior to the pandemic.

The COVID-19 crisis can serve as an opportunity to reach and educate children and youth who were not attending schools before they closed. UNICEF estimates that as many as 303 million children, or 1 in 5 children and young people, were out of school even before the COVID-19 pandemic forced most schools to close (UNICEF, 2018). Gender discrimination, disasters, armed conflict, language challenges, household poverty, child labor, and child marriage can all contribute to children not attending school (UNICEF, 2020b). Children with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to being out of school. Although the exact number of children with disabilities who are out of school remains largely unknown, recent studies suggest that children with disabilities are only half as likely to ever have attended school compared to children without disabilities (UNICEF & Mont, 2014). However, steps can be taken to ensure that alternative learning methods also reach out-of-school children by working with community leaders to help spread awareness about the availability of these resources. Additionally, when it is safe for schools to resume, education officials may want to explore the measures taken during this global pandemic that reached out-of-school children and encourage them to attend in-person schooling.

The current pandemic offers an unprecedented opportunity to not only make COVID-19–related stop-gap measures inclusive for all children but to also reimagine what instruction looks like once schools re-open. Successful interventions implemented during school closures have a good chance of being continued post-crisis, and we owe it to children globally to develop these interventions so that they are included from the start. The simple approaches described above can be used by education practitioners in any context when instituting either temporary or long-term learning, which will benefit children with and without disabilities. This is an unprecedented time, but the challenges education systems currently face do not mean that positive advancements cannot lead to meaningful outcomes. Promoting the education of all children, including those with and without disabilities, can be one of the positive outcomes.

Cited Resources

Dell, C.A., Dell, T.F., & Blackwell, T.L. (2015). Applying Universal Design for Learning in online courses: pedagogical and practical considerations. Journal of Educators Online-JEO, 13(2), 166–192.

UNESCO. (2020). COVID-19 educational disruption and response. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

UNICEF & Mont, D. (2014). Mapping children with disabilities out of school: Webinar 5: companion technical booklet. https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/IE_Webinar_Booklet_5.pdf

UNICEF. (2018). 1 in 3 children and young people is out of school in countries affected by war or natural disasters. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/1-3-children-and-young-people-out-school-countries-affected-war-or-natural-disasters

UNICEF (2020a) Accessible remote learning during COVID-19: Immediate approaches for countries to implement during COVID-19 to create accessible digital content. https://www.accessibletextbooksforall.org/stories/accessible-remote-learning-during-covid-19

UNICEF. (2020b). Reducing the number of out-of-school children. https://www.unicef.org/rosa/what-we-do/out-of-school-children

VARK. (2019). A guide to learning preferences. http://vark-learn.com/