This article was written by Wendy Kopp, CEO and Co-founder of Teach for All and was originally published on the Teach for All blog on 22 June 2020.

With 90% of the world’s children having been out of school during this pandemic, what are we discovering about remote learning? Will schools ever be the same? How should we use what we’re learning to reopen schools better? Is online learning the key to educational transformation? Will technology be a force for greater equity, or for exacerbating inequity?

Across Teach For All, our network organizations and their teachers and alumni educators have been working with heart and soul to keep students learning during this unprecedented crisis. From their experiences, innovations and leadership, we’re learning so much about the answers to these questions.

Here are three lessons we’ve gleaned from this worldwide experiment with distance learning:

- Education is about more than academics — and moments like this show us exactly why.

Through the upheaval the pandemic has caused, teachers have seen firsthand what’s most important to keep students learning: fostering student ownership of their education, their organizational skills and growth mindsets, their mental health, and other social emotional skills.

Focusing on holistic development has been necessary to keep students learning, and it will be necessary for equipping them to navigate an uncertain future. We’ve been forced to step out of the educational box we’ve been in for 150 years. Let’s take advantage of this moment and refrain from going back to our narrow academic focus.

One of the biggest challenges students have experienced, even where they’ve had full digital access, is the demands that remote education places on them to be independent learners, to organize their own time and not be distracted by being at home. Not all students are prepared for that. According to a study in Malaysia, “Students who prefer online learning indicated higher levels of readiness for self-directed learning… because they can learn at their own pace, manage their own time, learn new skills and have access to more information.”

Teachers are also in the thick of supporting their students through an enormous emotional challenge, as they struggle with uncertainty, isolation, stress, and in some cases unsafe or unstable homes. Before it’s possible to help students learn academic content, it’s crucial, and difficult, to build a safe, supportive classroom community.

Teach For Nepal fellow Bishwas Regmi quickly enabled his students to use Zoom, and planned to teach science through that and phone calls. But he soon realized that students needed a space to emotionally express their stress and troubles. So he gave his students an assignment: to write a lockdown diary which could include a range of topics such as their feelings, their daily routine, and the situation in their communities. One of his students shared in her diary how much she worried that all her preparations for crucial final exams, cancelled due to the lockdown, would now go in vain. Bishwas has since been able to help this student stay focused on her studies, despite the anxiety and stress from ongoing uncertainty. Reading the many stories such as this one that his students have been sending him, Bishwas has realized how important these communications have been to support students in these distressing times. Their continued engagement in academic work was dependent on receiving such socio-emotional guidance and support.

We’ve seen the importance of focusing on a broad set of outcomes for students. We can never let that go. Before we reopen schools and begin new school years, let’s consider what we want for our students. This means examining the challenges our society faces, the new opportunities that are presenting themselves, and our values and aspirations. Once communities and societies are clear on their visions for student success, they can consider the student outcomes to orient towards — and begin the process of reconsidering everything else, from how we train and develop teachers, to how we spend our time in order to reach those outcomes.

- We don’t need to wait until everyone has high-speed internet to teach well online.

Even in situations where internet speeds and reliability make it almost impossible to use Zoom, Google Classroom or Microsoft Teams for remote learning, we’ve seen the promise of leveraging low-bandwidth technology in education. Mobile devices with access to Messenger and WhatsApp have enabled a new level of differentiation and student agency, as teachers can engage with their students in different ways based on their needs, and students can share their progress and ask for help at their own pace.

When schools closed, primary school teacher Rabiah Chaudhry’s students in Pakistan’s capital Islamabad did not have laptops but most had access to phones that came with free data to access messaging apps. So Rabiah began to send video and audio lessons over WhatsApp, and she found her students watching lessons multiple times to master the material, sending back photos of their homework and asking her questions through voice notes. “I didn’t anticipate how well students would adjust to learning from home,” she says. “They were able to get the sort of individual attention they couldn’t in a class of 50.” Another benefit was that parental involvement increased, because parents could see what their children were learning.

Watch this video to learn more about Rabiah’s “WhatsApp School”

Rabiah’s is just one example of experimentation with asynchronous learning — where students learn the material on their own and reconvene with their teachers for discussion and support. She and her co-teacher plan on taking their “WhatsApp school” with them when schools reopen. With sufficient investment in technology and teacher development in digital pedagogy, we could achieve this level of personalization across the world.

Emefa Kumaza, a dedicated teacher in northern Ghana, went to great lengths to reach her students, tracking down phone numbers for as many as she could, sometimes for phones to be borrowed from neighbors. Despite this, she couldn’t reach half of her 67 students — they had no phone access at all. She taught those she could reach over conference calls, assigning homework and helping them set goals and schedules. Often these calls could only happen at night, after parents returned from work with the family phone.

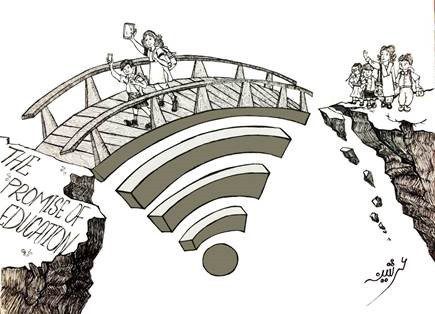

Worldwide, 45% of families still have no internet access, and even where internet is available, families often only have one device or access is spotty or too expensive to use regularly. To ensure that a worldwide push to leverage technology in education doesn’t massively grow educational gaps, and instead realizes its potential to expand educational opportunity for all, we will need to make a huge investment in ensuring universal access. The good news from our experience is that we don’t need all kids to have laptops and high-speed access to enable continuous learning. Prioritizing access to low-bandwidth technologies will make a huge difference.

Teach For Pakistan fellow Arsheena Gowani’s sketch captures the digital divide that teachers are overcoming to keep their students safe and learning.

- Keeping students learning with technology requires more of teachers, not less.

While there’s much focus on the digital divide and how this is exacerbating inequity, we’re seeing that the biggest divide is the gap between those students with teachers who build strong relationships with students and families, and have strong pedagogical skills, and those without such teachers. This is true in the most technology-rich environments and in the places with the least access.

Teachers are finding that engaging students often requires reaching out to entire families. When schools shut, Asmae El Idrissi began reaching out to her pre-school students’ mothers, to encourage them to help their children continue learning by accessing videos she would send on WhatsApp, and then sharing back with her the work their children did. Families in this traditional Moroccan community were reluctant to engage, but Asmae convinced some of the most influential mothers, who persuaded others. She also enlisted some of the fathers and other allies like the local grocery store owner in bringing around the fathers. Asmae’s relationships, the trust she’s built in the community, and a lot of energy in planning and providing lessons on WhatsApp have enabled her students to keep learning and strengthened their parents’ engagement in their education.

In a technology-rich Danish school, a student who serves on our Student Leadership Advisory Council reported that all the students had devices and connectivity, but of 22 students, a quarter of them never joined classes, another quarter attended sometimes, and a quarter came but didn’t do homework, leaving just a quarter who were fully engaged. She and the other students on our Council — some of the most driven students I’ve met — commiserated about how hard it’s been to motivate themselves through this era, and the crucial role teachers played in this. “It became really clear which teachers want to teach content and which teachers want to teach kids,” she said, highlighting the importance of teachers who reach out to students individually, build a sense of community among them, facilitate learning and provide feedback — rather than attempt to reach students through didactic instruction.

Maximizing technology’s potential to transform education will require a massive investment in recruiting and developing teachers to make the most of it. At the same time, perhaps technology can help us find a path to making teachers’ jobs more sustainable by differentiating teachers’ roles, as recommended by the Education Commission’s Education Workforce Initiative. One possibility is to have some teachers deliver online instruction via videos while others work with smaller groups of students to build community among them, motivate their ongoing engagement and provide individual feedback. From what we’ve seen, teachers have had to work harder than ever to keep kids learning during this era, so we will need to explore this possibility and others to make it feasible for committed teachers to fully leverage technology and maximize student learning and development.

Will we choose to make technology a force for equity or for growing inequity?

For years, the underlying assumption of many proponents of online learning has been that it will bring great teaching to even the most remote locations without the need for expensive, vast networks of teachers and brick and mortar infrastructure. Through this pandemic, we are indeed seeing many shining examples of online learning being used effectively — but these are being driven by dedicated teachers who know their students’ needs and are creatively leveraging what is available to them. If we are to make the most of technology to enable acceleration of educational progress, it will be through investments in teachers as well as technology.

Better leveraging technology could be a huge force for equity or a huge force for growing inequity, depending on our choices in the era ahead. Either we make massive investments in both technology and teachers, which could improve the education of all kids, or we make these investments only in well-resourced areas which will increase educational gaps still more severely.

This doesn’t mean that, even with adequate investments, students should always stay at home to learn. Learning from home will grow gaps and not shrink them unless there are many other interventions to ensure all students not only have digital access but are in safe spaces conducive to learning, and have access to nutritious meals and the other critical supports schools have come to provide. Moreover, one of the paradoxes of this pandemic is that it has shown us both that we can do more remotely than we had previously thought, and also that we need to be together more than we may have realized.

If we can use the learnings of this era — by orienting towards a broad set of student outcomes and investing in technology and teachers — the legacy of this period of upheaval could be a big step forward in giving all students access to the education that will allow them to flourish, so they can make the world a better place for themselves and all of us.