This blog was written by Vijay Siddharth Pillai, a recent graduate from the REAL Centre at the University of Cambridge, and a former Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellow in India. He currently works at the Education in Emergencies Office of the Ministry of Education in Afghanistan. This blog is part of a series from the REAL Centre reflecting on the impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on research work on international education and development. This has also been published on the INEE website and featured in the INEE COVID-19 Blog Series.

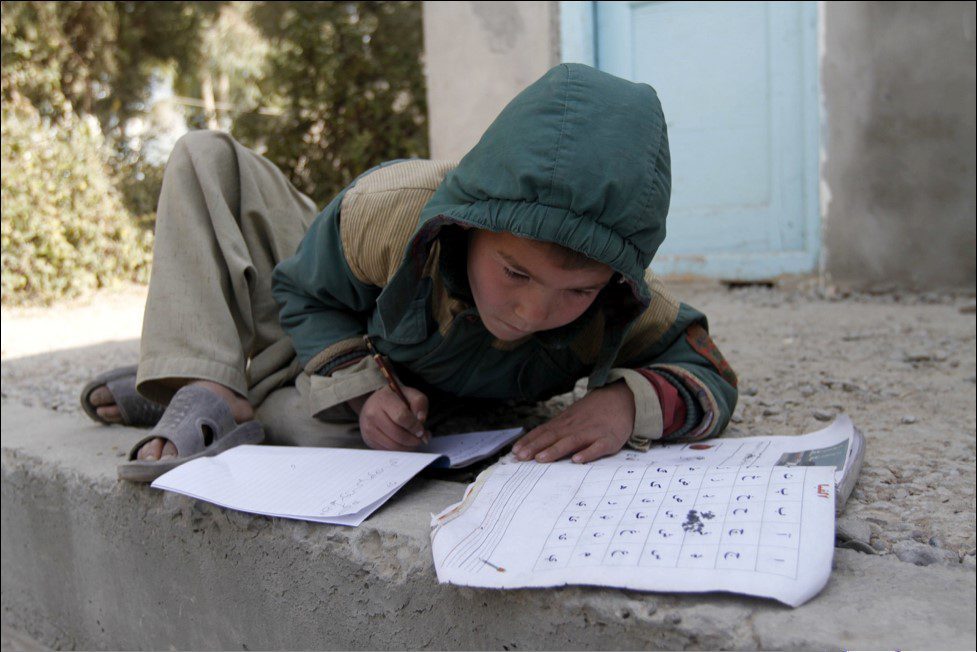

Afghanistan is developing print-based, self-instructional materials for learners to ensure a more inclusive response to the COVID-19 crisis.

With an extended period of school closures due to COVID-19 outbreak, countries are trying to ensure continuity of learning through alternate means. As governments, along with development and humanitarian partners, engage in the process of developing digital, video, and audio content for learners who are out of school, support also needs to be provided to children who don’t have access to the internet or the necessary devices for accessing this content.

Self-instructional print-based material, which supplements the textbook, needs to be provided to children so as to ensure that the Education Sector’s response to COVID-19 remains inclusive. Afghanistan is currently developing and reviewing such self-instructional material.

In classroom based teaching, the teacher is the central resource for learners. Understanding the diversity in the classroom, the teacher packages and repackages content for students who may be at different learning levels and have different learning styles so that learning occurs. The textbook aids the teacher in this effort.

In the absence of a teacher, traditional textbooks alone may fail to ensure active learning among children as such books often focus on explanation of facts, concepts, and theories. What is required in such situations is self-instructional material that not only provides information but also:

- defines what is to be learnt

- gives examples

- explains

- questions

- sets learning tasks

- answers learners questions

- allows learners to do self assessment

- gives study advice

The type of self instructional material developed for learners depends on the availability of textbooks and the kind of resources in it. In the absence of a textbook, the self-instructional material has to be exhaustive as it has to include content that explains the concepts. However if the textbook already is available with the student, the self-instructional material needs to focus only on resources that are absent and provide a viable self-study plan for the learner. Resources that may be absent in the textbook could include study tips, examples, self-assessment, summaries, etc., all of which enhances active learning and engagement with the students. If the textbook includes most of the above mentioned components, the self-instructional material can be minimal and may focus on the self-study plan for the learner.

A typical unit in self-instructional material has the following structure:

- Title of the Learning Unit

- Introduction

- List of contents

- Learning Outcomes

- Resources needed for this unit (This section might be repeated several times depending on the number of topics/sub topics; set time limits for each activity)

- Topic Heading/Sub-heading

- Read (pages/topics from the textbook)

- Read (new, supplemental text, written by you)

- Do (activity written by you; with answer grid for the learner )

- Do (self assessment written by you; with answer grid for the learner)

- Read (feedback written by you)

- Do (Tutor marked assessments written by you with marking criteria, time limits and date of submission)

- Summary/Key points

The focus can be on activities, examples, and self-assessment, and must be accompanied by feedback and explanations on the common mistakes committed by learners while attempting activities and questions.

More details about designing self-instructional materials, including best practices for writing and delivering educational content can be found in this free handbook: Creating Learning Materials for Open and Distance Learning: A Handbook for Authors and Instructional Designers. See also a draft version of our adaptation of this handbook for Afghanistan: Playbook for the Development of Self-Instructional Material for Home-based learning during school closures in Afghanistan.

Once the self-instructional material is ready, field trials of the self-instructional material (amidst social distancing) should be conducted. Self-instructional material should not only have space for writing the answers to self assessment questions, but also space to answer feedback related questions (“Was assessment 9 too easy/difficult?”; “Was the set time limit adequate for you?”; “Did you find the observation task too difficult?”).

No-tech, print-based responses will try to ensure that learning goes on in resource deprived areas. However, its effectiveness strongly depends on the ability of learners to actually read the self-instructional material. This is not a given, even among upper primary students, as more than half of the world’s children are expected to finish school without being able to read. Our inability in the past to ensure that they learn to read even while in school greatly impacts our current efforts to ensure that they can read to learn through these self-instructional materials while out of school.

So there is extra burden on us now to mitigate the impact of illiteracy through the use of illustrations (e.g. concept maps, flowcharts, diagrams, etc.), shorter sentences, transitional phrases (e.g. “first of all”, “on the other hand”, “to summarize”), and familiar and common words (e.g. “harmful” instead of “detrimental”). In any case, during these extraordinarily challenging times, we can’t let perfect be the enemy of the good.

One of the best responses I’ve read about keeping learning going in low-resource contexts.

Thanks Caroline… Glad that you found it to be relevant.

I agree.Congratulations. Can you be contacted?

Thanks Susan…you can contact me at pillai.siddharth2006@gmail.com

This is an extremely useful set of resources Vijay, thank-you. Self instructional materials may be useful too in ‘normal classrooms’ in the future The sections on self assessment and feedback are very important and perhaps deserve more attention. With an eye always on the young learner who has limited back-up resources at home, how do we ensure that self assessed ‘lack of mastery’ can, with suitable remediation, become mastery and a sound basis on which to proceed to the next unit?