This article was written by Linda Peck of AlignEd International

Schools are now grappling with how to transform the curriculum to address the unprecedented challenges that have arisen in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis and social justice protests. Whilst the initial focus was on catching up on learning loss, thinking has clearly moved on and there is broad recognition of the need for deep change in the curriculum. Absence from school has led to gaps in subject learning that need to be filled, but there is fundamental learning missing from the curriculum that has been absent for too long.

Approximately 30% of children in UK schools are of heritages other than White British. Given that the school curriculum should reflect the nation’s vision and ambition for all of its children, why, in so many schools, through the curriculum choices made by their teachers, do many children still learn that their lives and their communities are less important than those of their white peers? Some educators are too quick to offer excuses about why their curriculum is not more reflective of the diverse communities that make up the UK. One of them is the constraints of the national curriculum. In truth, the capacity to broaden the curriculum has always been there. What is needed, is for curriculum leaders and teachers to go beyond what they see in the examples provided by the Department for Education and in ‘off the shelf’ schemes of work and text books. It should be normal for a school to reflect the full diversity of the human histories of its children, its communities, its country.

We need to acknowledge that our national curriculum is deeply flawed and accept that the current government has no plans to change it. The 2014 revisions deliberately removed any explicit focus on racial diversity in Britain. The recently released guidance on relationship education has been interpreted in some quarters, as a warning to those schools that want to be more ‘progressive’. However, this guidance is non-statutory and schools do not have a legal duty to follow it. The duty to be impartial and balanced has applied since 1966. A British history education survey shows that currently, only 11 percent of young people taking GCSE history in 2019 studied modules that included the contributions of black people to our nation. Most GCSE literature syllabuses are also light in terms of representation of black and minority ethnic authors. This does little to open the minds of young people to our diverse heritage. It’s hard to conclude that the current curriculum is impartial and balanced. One might say it’s our legal duty to tip the scales back into equilibrium.

If, as school leaders, we believe that social justice is at the heart of our work, we must first agree what constitutes the body of ‘best knowledge’, and the cultural capital our children need to be prepared ‘for the opportunities, responsibilities and experiences of later life’. Whose culture should the curriculum reflect? Our curriculum choices are pivotal in developing confident young people who feel they have an equal stake in society. The new Ofsted framework introduced in September 2019 provided the much needed leverage to shift the focus away from exam results and back onto the curriculum. Beyond the already clear flexibilities within the national curriculum, non-maintained schools have further freedoms to plan their own curriculum, providing it is carefully thought through and equitable in terms of its breadth, balance and ambition. Some subjects have more scope for reflecting race and diversity, but it is possible, if we view the curriculum through a social justice lens, to ensure much better representation in content and resources in all subjects.

Children need to understand about historical, institutional and interpersonal racisms; how they affect all of our lives and how we see the world. Teachers need expert knowledge of these issues in order to ensure that the contexts, aims and content of every subject can contribute to the engagement and empowerment of every child. A first step will be to teach an honest, uncensored version of history: about the forces that have created racial and gender inequalities in Britain and more widely. This is not about offering up more resources for ‘black history month’ and then forgetting about it the rest of the year; it needs to be a carefully planned part of the full curriculum from KS1 to KS5.

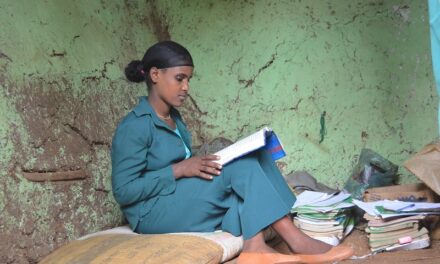

Any change in curriculum content needs to be aligned with an equally inclusive pedagogy. Content choice will only go so far in influencing how our children think about themselves and their communities. We need to develop their skills in thinking critically about the narratives they are exposed to as they mature. So, part of our teaching repertoire must include opportunities for young people to question what they read and hear from an early age. Thus, we provide them with powerful tools to think critically, analyse, evaluate, filter and debate. Learners need to feel that they have some level of control in their learning. Allowing young people to bring their own stories into the classroom acknowledges and values their experiences, as well as providing an invaluable learning resource for the teacher and other learners. A pedagogy that does not embrace the consideration of students’ own experiences, will always fall short of the mark.

Real change will only be achieved when the hidden curriculum, that conveys strong messages to our young people about their place in society, is also addressed and aligned to our values. The structures, systems and routines of every day school life need to be reexamined. There is little point telling children we value them if the message is contradicted by what they see. In schools where black and minority ethnic children only ever see themselves reflected in the people who serve their food or clean their classrooms, they won’t feel strong allegiance with the world of education or identify with the message that education is the way to create a better future. We need much better representation at all levels in the education hierarchy.

The way students are tested also has a big influence on curriculum priorities. Real transformation requires alignment with the curriculum, not only of pedagogy but also of assessment. We must continue to put pressure on the exam boards to reflect the diversity of the nation in their syllabuses.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks