This blog was written by Dr Jennae Bulat, Senior Director of the Teaching and Learning team in the International Development Group (IDG) at RTI International. Jennae co-authored this in collaboration with Julianne Norman and Elizabeth Randolph. The article was originally published on the RTI SharEd website on 27 May 2020.

With schools closed now for students in most parts of the world, instruction is being shifted to virtual teaching and learning. For those with greater access to digital resources, this instruction can include the use of digital devices—such as computers, tablets, and smart phones—to connect with students either synchronously or asynchronously using video-enhanced content. Where students and their families do not have such devices, mass media platforms such as radio and television are being used to transmit both static and interactive lessons for students as well as guidance tips for parents on how to support student learning while at home.

As important and effective as these approaches can be in fostering ongoing learning during this period of global crisis, we cannot lose sight of another important facet of student’s lives and ability to learn: their safety and sense of stability (UN Girls’ Education Initiative (UNGEI) and UNESCO, 2015). The international development community has begun to recognize the importance of social and emotional learning (SEL) and positive and safe school and classroom climate in promoting academic achievement in schools. Further, donors, such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), have invested millions of dollars exploring ways to bolster social and emotional skills within students and teachers alike, including ways to raise awareness among teachers about the importance of safe and positive environments. Unfortunately, removing students from the classroom does not necessarily remove them from risks of violence (United Nations, 2020; World Health Organization, 2019). Just as the effects of this global pandemic are felt by adults, it also impacts children whose routines and structures have largely disappeared (Stafford, et al., 2009). As the world grapples with how best to promote ongoing learning among children while at home it must, therefore, also continue to capitalize on improvements made in SEL development and child safety and security. Indeed, the current pandemic offers unexpected and unprecedented opportunities to ensure that progress achieved in SEL development and student safety is retained. For the education practitioners community, this means we must find and act in innovative ways to equip students, as well as their parents and teachers, with the social and emotional competencies they need to productively deal with the stressors and potential risks in their lives.

As important and effective as these approaches can be in fostering ongoing learning during this period of global crisis, we cannot lose sight of another important facet of student’s lives and ability to learn: their safety and sense of stability (UN Girls’ Education Initiative (UNGEI) and UNESCO, 2015). The international development community has begun to recognize the importance of social and emotional learning (SEL) and positive and safe school and classroom climate in promoting academic achievement in schools. Further, donors, such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), have invested millions of dollars exploring ways to bolster social and emotional skills within students and teachers alike, including ways to raise awareness among teachers about the importance of safe and positive environments. Unfortunately, removing students from the classroom does not necessarily remove them from risks of violence (United Nations, 2020; World Health Organization, 2019). Just as the effects of this global pandemic are felt by adults, it also impacts children whose routines and structures have largely disappeared (Stafford, et al., 2009). As the world grapples with how best to promote ongoing learning among children while at home it must, therefore, also continue to capitalize on improvements made in SEL development and child safety and security. Indeed, the current pandemic offers unexpected and unprecedented opportunities to ensure that progress achieved in SEL development and student safety is retained. For the education practitioners community, this means we must find and act in innovative ways to equip students, as well as their parents and teachers, with the social and emotional competencies they need to productively deal with the stressors and potential risks in their lives.

How to effectively promote SEL development among children and their parents, while simultaneously highlighting and trying to promote nurturing and enriching learning environments in the home is a daunting question. Under the leadership of USAID, however, projects are rising to the challenge in innovative ways.

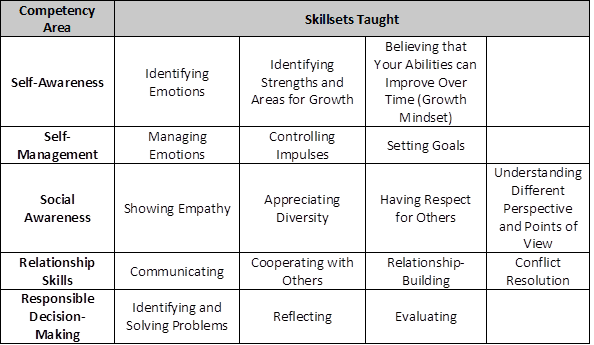

USAID’s Read Liberia education activity in Liberia is tackling this challenge by working directly with children in their homes, providing technical support to the Ministry of Education (MOE) in the development and recording of radio scripts as part of the MOE’s Education in Emergency Plan. Read Liberia’s early grade reading model, teaching and learning materials, and daily lessons are being adapted for national radio broadcasts, which are dramatically increasing the reach of the activity’s core programming. Core to Read Liberia’s approach is to help teachers inherently address social and emotional needs students bring to the classroom in order to remove barriers and facilitate learning. Even common strategies such as making safe spaces for students to respond to questions without fear of punishment and ensuring that even reticent students are supported in participating—strategies teachers are trained in—help students to feel nurtured and enable learning. Read Liberia continues to weave this type of social and emotional support in its radio-based lessons, helping students notice, understand, and respond to their emotions and feelings. This approach, adapted from CASEL’s competency model (CASEL, 2020), integrates through language arts lessons specific skills on which children can work independently or in collaboration with their parents (see Figure 1). For example, children are encouraged to explore their own feelings of empathy through guided questions around a story or a picture. Because a story or picture can depict a character as feeling frightened, uncertain, or sad, children are prompted to explore those feelings through questions, such as, “How do you think this character is feeling?, “Why do you think she may feel that way?”, and “What would you do to make her feel better?” Children are then prompted to self-reflect and identify what in their lives makes them feel frightened or sad and explore options for handling those feelings. This strategy is also an effective way to engage children in the story or lesson, as such questions help to make the story or lesson directly relevant to them. Concurrently, parents are engaged to think about how to model effective strategies for handling emotions and for showing children that they are being heard and not judged.

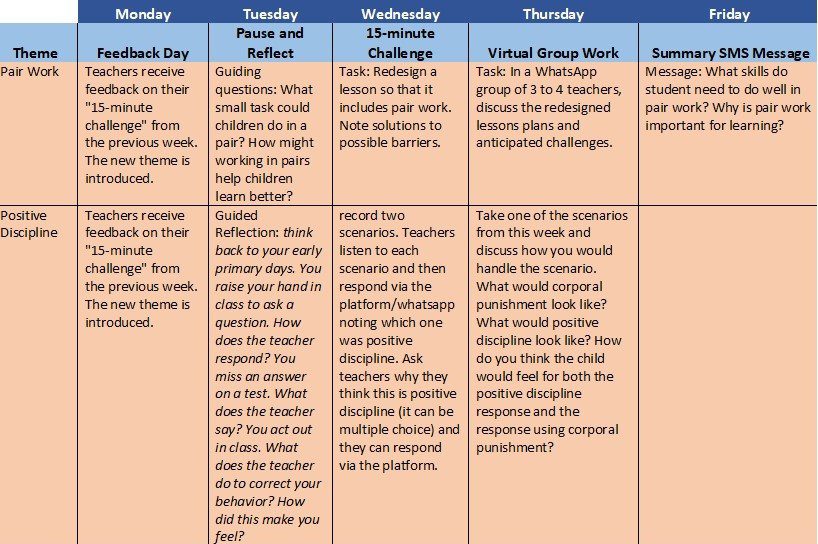

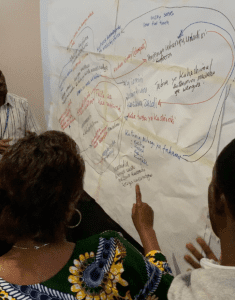

In Tanzania, the USAID Tusome Pamoja (TP) Project is innovating in SEL and safe school strategies by engaging teachers during school closures to continue building their SEL skills while they are at home. Prior to COVID-19 closures, the project was in the process of conducting a program, “Enabling a Safe School Environment through Social and Emotional Learning (SEL)”, to create safe learning environments and promote SEL in schools. TP had completed a workshop whereby teachers from the Iringa region worked together with TP staff to co-create a number of “safe school” and SEL activities that garnered significant local support and momentum. To keep generating ideas and continue the teachers’ enthusiasm, the team developed a remote support plan to promote this collaboration virtually during the pandemic. The plan uses localized WhatsApp groups with the same teachers (managed by TP staff) to offer a series of weekly prompts around a theme that mirrors the content teachers discussed during the workshop. In this system, daily prompts follow a set routine (see bullets below), with content changing by week (see Figure 2 for a sample week routine). Additionally, the TP technical team can collect data/responses from the teachers remotely and provide feedback.

In Tanzania, the USAID Tusome Pamoja (TP) Project is innovating in SEL and safe school strategies by engaging teachers during school closures to continue building their SEL skills while they are at home. Prior to COVID-19 closures, the project was in the process of conducting a program, “Enabling a Safe School Environment through Social and Emotional Learning (SEL)”, to create safe learning environments and promote SEL in schools. TP had completed a workshop whereby teachers from the Iringa region worked together with TP staff to co-create a number of “safe school” and SEL activities that garnered significant local support and momentum. To keep generating ideas and continue the teachers’ enthusiasm, the team developed a remote support plan to promote this collaboration virtually during the pandemic. The plan uses localized WhatsApp groups with the same teachers (managed by TP staff) to offer a series of weekly prompts around a theme that mirrors the content teachers discussed during the workshop. In this system, daily prompts follow a set routine (see bullets below), with content changing by week (see Figure 2 for a sample week routine). Additionally, the TP technical team can collect data/responses from the teachers remotely and provide feedback.

- Day 1. Prior week feedback: Teachers receive feedback from TP staff from the previous week’s activities.

- Day 2. Pause and reflect: Teachers pause and reflect about the theme by either thinking to themselves or writing in a journal.

- Day 3. 15-minute challenge: Based on the previous day’s reflection, teachers work on an activity, on their own, to operationalize their thinking and spark creativity. This activity could include designing or revising a lesson plan that takes the week’s theme into consideration and developing a new method of teaching content to students (i.e. via a game, group or pair work, etc).

- Day 4. Virtual group work: TP staff then facilitate virtual WhatsApp breakout groups for teachers to discuss their thinking and activity from the previous two days.

- Day 5. Plenary WhatsApp group: All teachers convene in the larger WhatsApp group for a virtual “plenary” discussion on the week’s reflection, activity and breakout group discussions. On the last day, TTP staff send out an SMS message via the WhatsApp chat with a summary of the week’s theme and learnings.

Ward Education Officers (WEOs) assist the TP team in disseminating the content to the teachers and managing the WhatsApp group(s). WEOs also collect feedback from teachers daily and provide remote assistance and support when needed. WEOs then send teacher feedback to the TP team who analyzes it and provides their own feedback in the form of coaching and support to teachers related to the content. Examples of feedback include, providing suggestions for teachers to better facilitate group and pair work, and reviewing a draft lesson plan or activity from a teacher. A positive externality of this remote program support has been the virtual community created. Creating a sense of community, even virtually, is critical to keeping motivation and momentum among teachers. Furthermore, TP’s Enabling a Safe School Environment through Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) activity has witnessed 100% teacher participation.

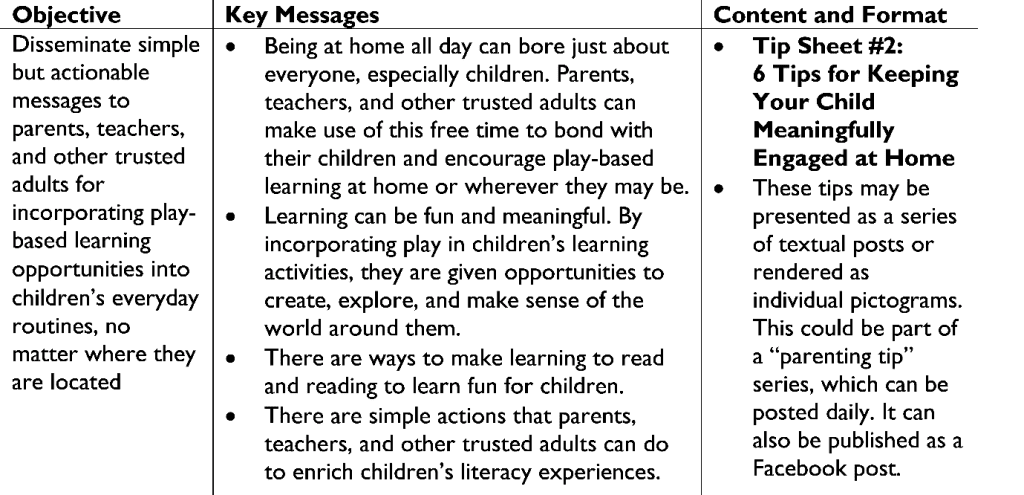

Finally, the USAID-funded project ABC+: Advancing Basic Education in the Philippines is developing a social- and mass-media communication plan to enable parents, teachers, and other adults in families and communities to best support children during this period of school disruption. This series of media-based posts will showcase USAID’s emerging response to support learning continuity during the pandemic, injecting key project messages on literacy, numeracy, and SEL that are aligned to USAID’s education goals and programming. Shared messages will include the following:

- SEL-focused tips for parents to talk to their children about COVID-19,

- Help parents and children cope with the pandemic through simple, everyday actions to avoid contracting and spreading the disease,

- Simple but actionable opportunities to incorporate play-based literacy and learning into children’s everyday routines,

- A curated list of free online reading materials and activities for parents and children to use, and

- Ways that teachers can engage in their own at-home learning and distance education.

The messages will also capture dispatches from the field, which provide insights into how Philippine schools, teachers, and students are coping with COVID-19, messages on resilience, and instances of partnership between the United States and Philippine governments (see Figure 3 for the intention and content of a sample message).

SEL is not and should not be limited to a set of child-centered activities. Teachers, parents, and the school and classroom climate have a role to play in fostering a child’s social and emotional development. Now is the time to ensure that students and the adults in their lives are given the tools needed to navigate the uncertainty and disruption that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to their lives. It is also an opportune time to continue to build teachers’ ability to address the SEL and safety needs of students once they return to schools. The cross-fertilization of ideas from virtual programming across projects and countries feeds innovation and helps to ensure that teachers, parents, and students build the SEL competencies they need to navigate this current crisis and are able to successfully transition back to their schools and workplaces when the time comes.

Citations

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) (2020). https://casel.org/core-competencies/

Stafford, B., Schonfeld, D., Keselman, L., Ventevoge, P., & Steward, C. L. (2009). The emotional impact of disaster on children and families. In PAHO, Practical guide of mental health in disaster situations. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/disasters_dpac_PEDsModule9.pdf

UN Girls’ Education Initiative (UNGEI) and UNESCO. “School-Related Gender-Based Violence Is Preventing the Achievement of Quality Education for All.” Policy Paper 17. New York: UNGEI, 2015.

United Nations. 2020. Policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on children. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/policy_brief_on_covid_impact_o…

World Health Organization. 2019. Violence against children. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-children