With the ‘COVID-19 Interviews’, NISSEM has embarked on a series of interviews with actors from government and civil society, in order to understand better the practicalities and implications of national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus is on countries in the global south. A full transcript of this interview can be found here. NISSEM expects to continue this series of interviews for some months to come, as systems emerging from the crisis rethink the content and practice of teaching and learning. UKFIET is co-hosting the first five of these interviews.

| Massey Samuel Tucker is the Education and Livelihood Technical Specialist with Save the Children Sierra Leone. Before this, he was at Plan International Sierra Leone, where he managed the global DFID-funded Girls’ Education Challenge project, targeting in-school and out-of-school vulnerable girls in remote communities. He also had a short time with Marie Stopes International Sierra Leone where he managed sexual reproductive health rights programmes. During Ebola, through his work with Plan International, he contributed to adapting the interactive radio teaching programme to ensure continuity of learning while schools remain closed. |

|

| Mariana Martinez is Handicap International’s (HI – now known globally as Humanity and Inclusion) Inclusion Technical Specialist for Sierra Leone. She has been with HI for 18 months and has worked in the disability field for about 15 years. She is originally from Mexico. She holds a BA in Education and an MA in Disability. Before moving to Sierra Leone, she worked in Malaysia for three years as an inclusion coordinator, running community programmes. |

|

“The government has been very much proactive in the fight against COVID, especially in ensuring that children learn, even during the pandemic while they stay home. I can link the success of this to Ebola and the lessons that were learned.”

In Sierra Leone, lessons learned from the education sector’s response to Ebola are still fresh. When COVID-19 struck, the Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education immediately formed working groups, namely: communication; distance learning; school reopening and readiness; and policy, operations and planning. Not only was the government able to react fast, “the closure of schools was announced even before the first case,” Mariana says. Also, “they knew what had worked and what didn’t work last time.”

Part of the response was the use of radio. According to Massey, “It came out clear that this was necessary and effective for kids who stayed at home during school closures. However, it had some lapses. It did not reach remote and marginalised communities… There’s very remote areas that don’t have a signal.” For most children, the radio lessons are also one-directional.

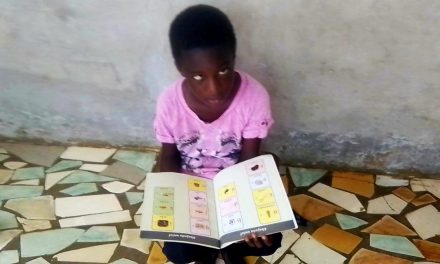

Textbook distribution in Sierra Leone is reportedly good, so most students have books at home, which the radio lessons support. Mariana adds that “the radio lessons are somehow designed so that the child or the student can follow with their books and without necessarily needing an adult there… It’s mainly a one-way process. Some of the NGOs working in the field have tried to collect feedback from students and their families, but it’s more of an external effort as, as far as I know.”

Massey describes plans to make the radio lessons more two-directional: “Discussions were held … that it would be good to have at least 30 minutes after the lessons where phone-in programs can be done. So that an opportunity can be given to the schoolchildren to at least ask questions and give feedback on the quality or the content of the radio lessons and as well have some kind of a feedback system at community level, where parents and school authorities can be engaged … They are working on it.”

For logistical reasons, in most government schools, teachers have not played much part in maintaining children’s learning. Mariana describes the problem: “Most teachers went back to their own homes, their own communities, and many are not in the community where their students are. Also, some students’ communities are far from the schools themselves. So, for teachers to reach the students is difficult. Different organisations are doing different things. For example, at Handicap International[1], through one of our projects, we have a network of community-based volunteers and we have a few, we call them, itinerant teachers who are specialised on disability and inclusion. But we have been able to work through the itinerant teachers and through the community-based volunteers to reach the students and make sure, first of all, that they are doing okay, their general well-being, and then trying to find different ways to support their learning through this period.”

Local initiatives are able to respond differently. Save the Children conducts learning circles in some areas. Massey notes that “Because COVID regulation says you can’t have more than 10 people, we only allow 10 school children per session. We have link teachers. They meet twice a week with the kids and they have supplemental lessons with them.” However, not all teachers work in government schools. A large number are volunteers in community schools.

Massey describes the psychosocial challenges: “After the Ebola, of course, the back to school messages were embedded with psychosocial support for the kids returning to school. And also, while not nationwide, many teachers benefited from psychosocial support training. The problem is with retention, because most of the skills and knowledge they gained were easily forgotten after the end of Ebola and people went back to their normal behaviours and forgot about the psychosocial aspects of supporting the kids. And this has come up again when COVID-19 surfaced.”

Massey reports that “fake news” in the country can be a big issue: “I can remember at one point, you know, it was a kind of funny note that someone had written. Some health officials went to conduct normal vaccinations in school, it was polio, and this fake news went around that people were moving around infecting schoolchildren with the COVID-19 virus. Parents had to rush to school to get their children from school and carry them home.” Mariana agrees: “It is a huge issue. I think in that sense the Ebola experience didn’t necessarily help us because at the beginning there was a lot of panic. That gave way to this fake news. Panic, of course, was coming from the experience the country had with Ebola, but as it progressed and people realised it was not like Ebola – at least it didn’t seem to be as deadly as Ebola – a lot of fake news started coming out that that the virus wasn’t real, that it didn’t exist, that it wasn’t in Sierra Leone, that it is all politics, and so on.”

Massey summarises the national response: “The government has been very much proactive in the fight against COVID, especially in ensuring that children learn, even during the pandemic while they stay home. And I can link the success of this to Ebola and lessons that were learned.”

This is part of a series of NISSEM COVID-19 Interviews. The series includes:

Responding to COVID-19 in Uganda: Interview with Baale Remegious

Responding to Covid-19 in Kenya: Interview with Lucy Maina and Ngángá Kibandi

Responding to COVID-19 in Lebanon: Interview with Rima Malek

Responding to COVID-19 in the Bahamas: Interview with Marcellus C. Taylor

[1] Now known as Humanity and Inclusion, but still operating as Handicap International in Sierra Leone.