This blog was written by Ricardo Sabates Aysa, Professor of Education and International Development in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge and member of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre. It was originally published on the Tony Little Centre for Innovation and Research in Learning website on 22 September 2020.

The impact of school closures on children’s learning in unfamiliar languages

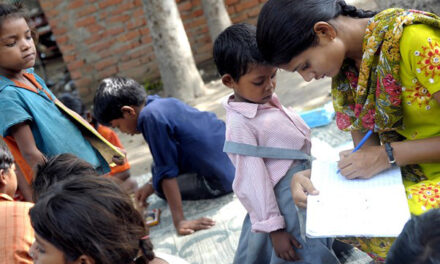

Ensuring the continuity of learning during and after the COVID-19 pandemic poses a serious challenge for educators and governments all around the world. This is particularly problematic in those multilingual environments in the Global South where resources are constrained and many children lack basic foundational skills. Many children in these environments do not have access to learning resources or activities in their mother tongue, or in a language they understand.

According to UNESCO, as much as 40% of the global student population in 2016 were not being taught in a language they spoke or understood, and half of the world’s students have been out of school or university during the pandemic. For those children who receive their education in a language other than their mother tongue, will this result in a greater impact on their learning loss during and after the pandemic?

In this blogpost, I argue that providing teaching and learning resources and activities in a language that is unfamiliar to learners does not benefit these children, and indeed can be detrimental to their learning. Restarting education in a language that children are unable to understand, whether fully or partially, is likely to not only reproduce but exacerbate existing inequalities in literacy acquisition faced by children from linguistic minorities.

The blogpost engages with the importance of mother tongue education, drawing on evidence gathered from a research project in Ghana. This project was undertaken between 2016 and 2018 in collaboration between the University of Cambridge’s REAL Centre and partners (which include RTI International, the Centre for International Education at the University of Sussex, IMC Worldwide, and PAB Development Consultants Ltd in Ghana). I focus on four areas:

- learning in one’s mother tongue,

- learning loss for those who do not understand the language,

- learning consequences from changing the language of instruction, and

- linguistic diversity and foundational learning.

The Complementary Basic Education (CBE) programme in Ghana

The Complementary Basic Education (CBE) programme in Ghana was designed to provide out-of-school children (aged 8 to 14) with access to basic literacy and numeracy instruction in 11 mother tongue languages. The nine-month accelerated learning programme aimed at delivering academic skills centred around primary grade 3 (in which pupils are typically 7 to 8 years old) so that out-of-school children could make a transition into a nearby government (i.e., state) primary school. The programme began in 1995, initiated by the Ghanaian NGO School for Life, and was expanded in 2013 with support from the then UK Department for International Development (DFID) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

We followed a cohort of around 2,000 children who participated in the CBE programme in the academic year 2016-17. We assessed foundational literacy using an assessment tool translated into 11 local languages, at the beginning of the CBE programme in October 2016. This assessment tool captures progressive literacy skills, starting from simple letter and sound recognition, then moving to word recognition, reading a simple sentence, a paragraph and finally reading comprehension to the level of grade 3 in primary schools. These children were re-assessed at three more points in time:

- after completion of the CBE programme (June 2017),

- at the beginning of the transition to government schools (October 2017), and

- at the end of the first year in government schools (June 2018).

Learning in one’s mother tongue

On average, we found large improvements in foundational literacy during the nine months of the CBE programme. In particular, the proportion of children who were not able to even identify words or sounds declined from around 13% to 4%. Those who moved beyond the ability to read a simple sentence increased by 35% during this period. In terms of language, however, we found large variations in literacy gains across languages. For example, students learning in Brifo and Kasem showed significantly larger literacy gains than students learning in Twi. Students learning in Gonja, Dagaare, Kusaal, and Gurune showed more improvements than Twi students, but only for some of the literacy subcomponents of the assessment; Sissala and Dagbani students improved less than Twi students.

The significant improvements in mother tongue literacy supported students in the continuation of their education after they completed the CBE programme. More than 85% of children in the CBE programme made the transition into local government schools.

Yet, for many students, the transition into government schools also meant a transition into a new language of instruction. The official language policy of Ghana indicates the use of one of the six official Ghanaian languages up until primary grade 3. From grade 4 onwards, English becomes the official language of instruction and one of the six official languages is only taught as a subject. Therefore, variations in relative gains made by students of different languages were a cause of concern, particularly for those students who made the transition into a different linguistic environment.

Learning loss for pupils who do not understand the language

There are two important aspects to understand in a complex multilingual environment such as Ghana. First, due the country’s language policy, nearly 47% of the students enrolled in the CBE programme changed language of instruction when they transitioned into government schools. Many students in Ghana face a new linguistic environment for their first time in school. Second, the linguistic diversity in certain areas of Ghana cannot be captured by the language of instruction used in the classroom. For instance, only 40.6% of students made the transition into government schools where the language of instruction was the same as their own language and the one used by the CBE instructor or facilitator.

More importantly, only 43% of these students indicated that they were able to understand the language used by the teacher. Therefore, linguistic diversity exists both between and within communities and within the classroom.

Between the end of the CBE programme and the start of the first year in government schools, children who completed the CBE programme spent about four months out of education, due to the break between academic school years. Since we measure literacy between these two time points, we can estimate the learning loss in foundational literacy during the transition period.

For children who moved into a new linguistic environment, we estimated an increase of 33% for those who were unable to read a paragraph, relative to those who had continuity in their language of instruction. More importantly, we also found large differences in learning losses even for those who had continuity in language. For example, for those students unable to read a paragraph, we estimated a difference of 15% between students who understood the language and students who indicated that they did not understand the language used by the CBE facilitator.

Considering that about 60% of the learning gains from the CBE programme are lost, on average, as a result of the long break before the start of the next academic year, the previous relative differences are large. They indicate that for children without language continuity the learning loss could be as much as 85% of their previous learning gains, whereas for children with language continuity it may only be 40% of the previous learning gains.

Learning consequences from changing the language of instruction

We further investigated whether students who changed their language of instruction managed to catch up in literacy in the new linguistic environment. To do this, we divided our investigation between:

- those children who transitioned in primary grade 3 and below, and therefore engaged in a local language as a language of instruction, and

- those who transitioned into primary grade 4 and above, and therefore continued their education in English as a medium of instruction.

Our results show that children who transitioned into primary grade 3 and below, where the local language is still the main medium of instruction, managed to catch up in letter and sound identification and had similar rates of progress for reading comprehension relative to children who transitioned into the same language. This may suggest that they had developed enough literacy proficiency in their mother tongue before the transition into government schools where a different local language is used. However, children who transitioned into grade 4 or above, where the local language taught is different from their mother tongue, did not manage to close the gap in foundational literacy. A plausible explanation for this result is the limited instructional time in the new local language combined with a shift into English as the language of instruction.

Linguistic diversity and foundational learning

Language is diverse, not just linguistically, but socially and culturally. In further work as part of this research, we asked whether foundational learning trajectories over time were affected by the ‘linguistic distance’ between languages – that is, how closely related a language of instruction is to a child’s mother tongue (e.g., whether it is a member of the same family of languages as the mother tongue).

To investigate this, we looked at only students who transitioned into grade 3 and below, and estimated whether there were differences in literacy losses for children who moved into a linguistically distant language of instruction (i.e., a language outside of the family of languages to the mother tongue). We found that 80% of children who moved into a linguistically distant language were unable to read at the point of transition. Furthermore, there were limited improvements in foundational literacy in the new language as a result of one year in primary schools.

Considerations for re-opening schools after COVID-19

For children who learn in a language other than their mother tongue, will this have a greater impact on their learning loss during and after the pandemic? From the research outlined above, I would argue that the provision of materials, resources and activities in a language that is unfamiliar to learners is detrimental to their learning. Restarting education after school closures, in a language that children are unable to understand, is likely to reproduce and exacerbate existing inequalities in literacy acquisition faced by children from linguistic minorities.

To lessen the impact of learning loss as a consequence of COVID-19 on those children receiving an education in a language other than their mother tongue, we must be attentive to the specific and additional needs of these learners – both during school closures and as schools re-open.

The research for this blogpost was done in collaboration with Dr Emma Carter and Professor Pauline Rose from the REAL Centre at the University of Cambridge, Professor Kwame Akyeampong from the Open University (previously University of Sussex), Dr Jonathan Stern and Dr Jennifer Ryan from RTI International, and Mr Kieran Daly from the Linguistics Department and the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge.