Think Local: Support for learning during COVID-19 could be found from within communities

This blog was written by Ricardo Sabates, Reader in Education at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge and member of the REAL Centre. This blog is part of a series reflecting on the impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on research work on international education and development. It has also been posted on the EdTech Hub website, the University of Cambridge Faculty of Education website and Cambridge University Press.

Over the previous weeks, there have been several blogs with ideas for continuing to provide learning opportunities for the majority of the world’s children whose schooling has been affected by COVID-19. Whether this is about the challenges and opportunities imposed by COVID-19, or how education systems are managing this situation, including how Ministries of Education are collaborating with private service providers, a strong focus tends to be on the use of educational technologies, both online and off-line to reach the majority of children. While I agree on the use of educational technologies (EdTech) as an aid to learning, there are important lessons that I would like to highlight from our ongoing research at the REAL Centre which I believe should also unleash the potential of communities to tackle this crisis, in many cases by boosting the potential of technologies to reach many.

Supporting volunteers to serve their communities

First, our research with the PAL Network has highlighted the importance of volunteers who are willing to support children’s learning. These volunteers are usually members of the communities who have supported the collection of 7.5 million citizen-led assessments in more than 40 languages, have translated information from assessment into actions and have themselves supported children’s learning with extra-curricular activities. We estimate that the PAL Network members have mobilised around 690,000 volunteers in 14 countries across the Global South. While social distance remains an important medical advice to abide during this COVID-19 pandemic, many of the PAL Network volunteers are young people, and more likely to be connected via social media and other means of communication available in more remote areas. How can we unleash the potential of volunteers to serve their communities, particularly in terms of their role as intermediaries between information or availability of educational materials and the use of these by parents in children’s homes.

Engaging with locally-trained facilitators

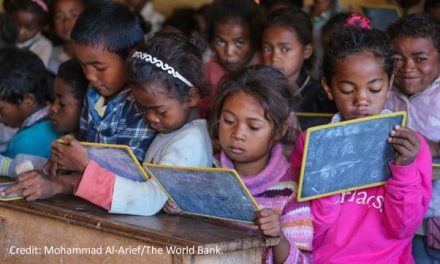

Second, we have researched the potential of locally-trained facilitators to support the education of out-of-school children and young people, whether this is through Speed Schools in Ethiopia, the Complementary Basic Education Programme in Ghana or the Siyani Sahelian Programme in South Punjab, Pakistan. Our research has demonstrated that local facilitators are able to enhance foundational literacy and numeracy skills for children who have never been to school or those who have dropped out without completing basic education. The power of local facilitators lies in their ability to communicate and use mother tongue with learners and establish a solid foundation for literacy. For many learners, the linguistic environment of the school takes place in a different language, and many do not have the resources to be able to understand what is being taught in class. Mother tongue education has been central for early learning in many multilingual contexts of the Global South. Are there resources developed in mother tongue available for local facilitators? Can technology be used to deliver resources to local facilitators to unleash their potential to serve their communities in terms of pedagogical support?

Engaging with parents

We have also undertaken research with parents, as key stakeholders of the educational system. The short route of accountability in systems of education place parents at the centre of monitoring and decision-making for school improvement plans. This is in the form of parent-teacher committees or associations. While many of these parent-teacher associations have been dysfunctional, our research with ASER Centre about Pratham, the largest educational NGO in India, suggests that there is a massive potential for parents to support their children’s learning. Pratham has been working with parents and producing resources to be used at home, even for parents who are illiterate. Our research indicates that overwhelmingly, 95% of parents believe that the responsibility to a child’s education was theirs. Even in rural areas of Uttar Pradesh we found that 67% of the parents checked their children’s notebooks and 56% of children got some help with their homework – mostly from their parents (68%) and siblings (31%). Therefore, there is a massive potential for parents to support the education of their children, which is likely to take place in mother tongue and use less traditional methods for knowledge sharing and practices.

Measuring learning

We have also engaged with broad measures for the concept of learning. For several of our projects, we have measures of literacy and numeracy, but we have also included measures of non-cognitive skills. Many of our programmes have an important component for life skills enhancement, such as the CAMFED programme in Tanzania and Zimbabwe which we have evaluated. The Siyani Sahelian Programme in Pakistan focuses on girls’ empowerment and gender equality. For the Research in Improving Systems of Education (RISE) in Ethiopia, we have measured several psychosocial scales suitable for the Ethiopian context. Therefore, while learning is taking place outside of the schools due to COVID-19, we must be committed to understanding the potential of children to learn with their families a broad set of skills, whether these are for livelihoods, life skills, or indeed by enhancing literacy and numeracy across and between generations (from parents to children and between siblings). Perhaps we may expect a deficit in certain indicators of learning, but we should not undermine the role of volunteers, local facilitators, parents and other community leaders in supporting most children who will be out of school for an unknown period of time.

Support through off-line methods

Overall, while social distancing measures prevail, the role of parents is essential. While there are many schools which are providing resources online and many open educational resources, these are usually only available to those who are able to access them. For the majority of children living in areas with no connectivity, it is indispensable to put together resources that are accessible to parents, potentially via text messages or WhatsApp. Volunteers and local facilitators have a role to play in this situation, potentially as intermediaries between the designers of educational resources and parents. We should also think about traditional ways of information sharing, as many communities still use audio amplifiers to inform the community about diverse news and events. While these can be used for communication about social distancing and personal health care, their role for learning should not be ignored.

This is an important post. An extra resource are children themselves. Please see the CHILD to CHILD website http://www.childtochild.org.uk. I would be interested to hear from anyone on this PAL network which has used CHILD to CHILD in the past or present. Susan Durston, CHILD to CHILD trustee. Find me on LinkedIN

Dear Susan

We will pass on your message to our colleagues from the PAL Network.

Indeed, in our blog here we acknowledge the important role of siblings and other children cohabiting for learning. Also, my work with Professor Nidhi Singal has highlighted learning challenges not just for children with disabilities but also for children living under the same household.

Singal, N., Sabates Aysa, R., Aslam, M., & Saeed, S. (2018). School enrolment and learning outcomes for children with disabilities: findings from a household survey in Pakistan. International Journal of Inclusive Education https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1531944 Paper available at:

https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/286295