This article was written by Pauline Rose, Director of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge. It was originally published on the Conversation website on 26 November 2020. It was also published on the Global Citizen website on 30 November 2020.

The UK government’s 2020 spending review includes a cut in international aid, from 0.7% of gross national income to 0.5%. My research shows that this will have severe effects on the lives of girls worldwide.

Earlier this year, my colleagues and I at the University of Cambridge published a report highlighting the urgent need for political leadership to address a global learning crisis in girls’ education in low and middle-income countries.

That review was commissioned by what is now the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. It contained powerful reflections by the foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, who commented: “This problem has a real cost – not only in loss of talent and potential – but on communities, societies, and the global economy … It is time for leaders to step up and act.”

Despite this, the spending review released on November 25 outlined the cut in the 0.7% of national income allocated to foreign aid, a principle supposedly enshrined in law. Chancellor Rishi Sunak stated that this cut was temporary and would return to 0.7% when the UK’s finances allowed.

But cutting this aid, even before one considers the devastating effects of COVID-19, will have real implications for the life chances of millions of young women.

An urgent issue

Prior to this year, 130 million girls were out of school. This number will have increased as inequality gaps have widened as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The UK’s recent record in addressing girls’ education and that of marginalised children in the world’s poorest countries has rightly gained considerable praise and respect.

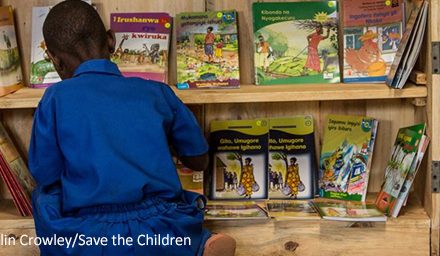

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office is responsible for the Girls’ Education Challenge programme, which began in 2012. It has worked across 18 countries to ensure girls there can actually complete their education, through support from communities, stronger school management, and engagement with partner governments.

In September last year, the prime minister himself renewed his personal commitment to supporting the empowerment of women and girls around the world by boosting funding aimed at ensuring they receive a quality education. However, the decision to cut foreign aid leaves a question mark hanging over significant programmes.

Baroness Liz Sugg, who resigned from her ministerial role following the announcement, was the UK’s special envoy for girls’ education.

In that role, she had been leading an action plan on girls’ education, engaging with a range of researchers and practitioners for its preparation. The plan may still be launched, but the UK’s commitment to stepping up action for the most marginalised girls is called into question in the context of an overall cut in aid funding.

These direct effects are only part of the issue here. Detailed research in low and middle-income countries has emphasised that girls’ education cannot be supported in a vacuum.

Interlocking factors

The global Save Our Future campaign, which calls for education to be prioritised in responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, focuses on the importance of mobilising resources in general for the poorest countries in the world.

The only way to help girls access school and stay there is to adopt that whole-system approach. That means that foreign aid must also address wider issues that currently limit women’s life chances beyond education. Research shows that progress within girls’ education requires action to support gender equality beyond it.

So even if the prime minister stands by his commitment to protect girls’ education directly, he will still put it in danger by cutting budgets elsewhere. As researchers in international development increasingly understand, if you remove one part of the programme, the entire structure begins to fall apart.

Where access to education is low, incidents of forced marriage, female genital mutilation, gender violence, teenage pregnancies, and poor family health are high. New data shows that before COVID-19, one in three adolescent girls in Ethiopia were likely to be married, compared to one in 15 adolescent boys. These risks are likely to be exacerbated in the context of the current pandemic.

Some commentators have, of course, suggested that foreign aid is often wasted money, and fails to reach the people it is designed to help. The government’s commitment to date to promoting evidence-based approaches to what works in international development has ensured this is not the case.

Research at the University of Cambridge also indicates that this is a false argument. We recently published research showing that while getting the most disadvantaged girls into school might require a large financial investment, there are massive benefits, with positive spill-over effects for boys too.

Andrew Mitchell, the previous international development secretary, stated in parliament after the announcement of the aid cut that “the 30% further reduction in cash as a result of the cut in [international aid] will be the cause of 100,000 preventable deaths, mainly among children”.

That echoes the warning of nearly 200 charities – not to mention five former prime ministers – that cutting foreign aid is an ethical and strategic error. The evidence on the good that the UK’s work has begun to do for the poorest people in the world – particularly disadvantaged girls – highlights the realities of the human cost involved.

In 2019, the government stressed the need for action and leadership on girls’ education. Wherever it chooses to swing its axe on the foreign aid budget, it is now difficult to see how that standard will be maintained.