This blog was written by Le Thu Huong and Teerada Na Jatturas, UNESCO. Le Thu Huong is a Programme Specialist at the Education Policy Section, UNESCO – her expertise includes analysing and planning socio-economic and education policies and development aids in international education development. Teerada Na Jatturas has an MPhil in Digital Communications from the Communication and Media Research Institute, University of Westminster, UK, where she defended her thesis on digital rights of at-risk internet users. She is presently a consultant at UNESCO analysing education and technology for educators.

The use of electronic assessment (or e-assessment) can be traced back as early as in the 1960s, yet its adoption as a modality of learning assessment remains rather limited to a number of contexts and education levels, leaving ample room for exploration, learning and adaptation. In this blog, we will reflect on the broad utilisation of electronic assessment, its conditions and the potentials it offers to support teaching and learning with severe restrictions to normal school operations, for instance, due to COVID-19 crisis.

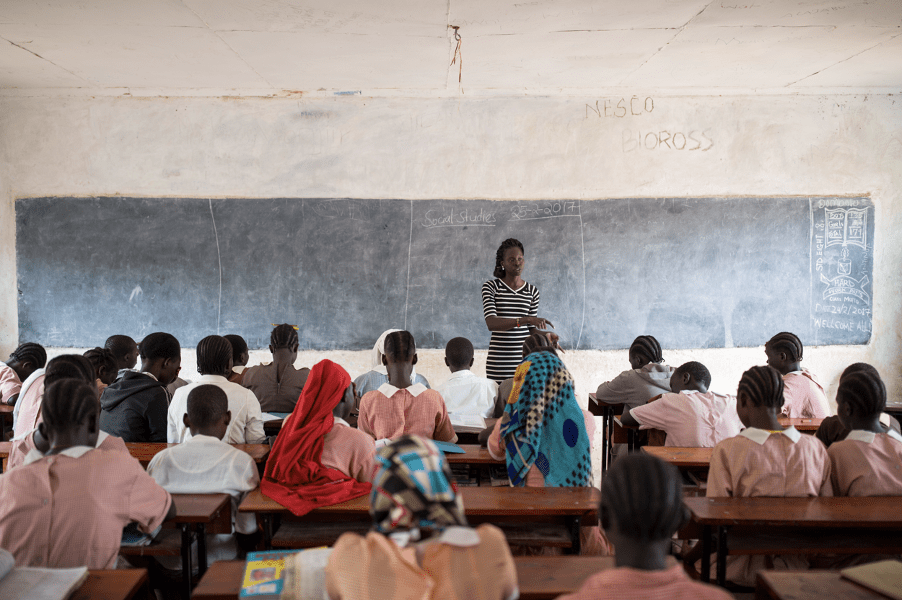

A RTI employee shows an enumerator how to use an electronic version of the Early Grade Mathematics Assessment (EGMA) on the Kindle. Nairobi, Kenya. Credit: GPE/Deepa Srikantaiah

So what is e-assessment? E-assessment in the educational context (interchangeably also called online or on-screen testing, or computer-based assessment) refers to the use of information and communication technology (ICT), often with the support of web-based assessment tools, in education. It emphasises the interaction between the student and computer during the assessment process, for which the test delivery and feedback provision are implemented by ICTs. It can be used both as a learning achievement test, which measures the student mastery of academic content, and an aptitude test, which is used to determine placement for specific educational paths, such as in technical and vocational education and training programmes. Likewise, it can also be conducted as tests (formative assessment) or exams (summative assessment).

The benefits

The use of computer-based assessments over traditional tests and exams in a controlled classroom or an exam hall, is attributed to several advantages: including flexible test location choices, quicker displaying results, preserving the environment as educational settings go paperless, and notably saving the human resources, logistics and administrative costs during the organisation and marking of tests and exams. Some authors, for example Ridgway, McCusker and Pead (2004) also underline some of the e-assessment potentials in

- supporting student learning (including through user-friendly interfaces, tests as games, and simulations, which resemble learning environment and recreational activities; immediate feedback for students, and facilitating group work projects), and

- enhancing the measurement of learner outcomes (especially in digital skills or problem solving skills).

As we keep a neutral position in debating whether or not e-assessment is a beneficial choice in promoting student learning, we only present our observation here to demonstrate a consistent trend in the adoption of e-assessment in countries that have ranked middle to high in the scale of the digital adoption index.

The challenges

Although e-assessment has been adopted in some countries (such as Australia, Belgium, Egypt, Estonia, Germany, Italy, India, Jordan, New Zealand, Norway, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, UK, and USA, according to our data), they are not universal for all education levels. The main reasons are ranging from high investment costs, the “digital divide”, and lack of technical know-how to the concerns over online privacy and unauthorised access or use of personal data (Marias et al. 2006). The cybersecurity issue pertinent to the education sector may involve the breach of the web server and central infrastructure, the mishandling of learners’ data with algorithms, and the deception in student authentication and assessment location. In addition, the fact that not all students and teachers are familiar with online examination systems (Alruwais 2018) present a formidable challenge for them to both taking e-assessments and troubleshooting IT-related problems during on-screen tests.

Country experiences in implementing e-assessment

Our review of country experiences with e-assessments has shown that online exams are mostly adopted in high-income countries and at higher education level. The benefits of e-assessment are not automatically realised, but are subject to a number of the following conditions:

Readiness of infrastructure, connectivity, and end-users. The accessibility of reliable electricity, internet connection and computer-mediated devices are crucial for implementing e-assessments. The country experiences reviewed so far demonstrated the importance of contextual matters, such as technology compatibility, system reliability, clear communication, logistics, and support for students and teachers when implementing e-assessment. This phenomenon especially occurs in India, UAE and the UK, wherein students either feel psychologically burdened about moving from paper-based to computer-based exams or experience technical difficulties during online exams, despite living in countries with relatively advanced technology. Teachers and learners alike also feel reluctant to conduct and take e-exams due to limited ICT skills (as in Jordan) or inadequate access to digital devices (as in Australia and India). This can be addressed by providing training on e-assessment, including organising trial tests for students as in Estonia.

Protecting digital privacy and security. Learner privacy is not just the issue of social norm or culture, but also the matter of safety and security in cyber space. Thus, student digital privacy and security should be protected from unauthorised access (that is third parties such as advertisers and attackers). Since e-testing is performed on tech companies’ platforms and/or software, they can harness a bulk of data belonging to exam administrators and students. Public and private entities in the education sector should ensure that digital security measures, such as using end-to-end encryption and strong privacy laws (notably the General Data Protection Regulation – GDPR – and the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act – COPPA), are put in place to maintain student privacy.

Ensuring academic integrity. The employment of online proctoring throughout the exam may prevent dishonesty. Remote proctors, which are mostly outsourced to a third country performing online invigilating during the exams, are seen as a solution to solve the issue of false authentication and assessment location of learners. However, a balance should be maintained between authenticity and student rights to privacy from surveillance. The role of online proctoring should be strictly used to detect unauthorised software on student computers and to monitor typing styles and the presence of unauthorised persons in the exam area with the assistance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) facial recognition. In this way, it is to ensure that the students’ understanding of the subject is graded fairly, while the prevention of impersonation and plagiarism is established, especially in the context of distance learning. Australia, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, and USA have adopted remote proctors to address the potential improbity of learners during online exams.

An opportunity for transformation

The COVID-19 pandemic has distinctly accelerated the transformation of distance teaching and learning as never seen before, so does the same follow for assessment? This rapid review of country experiences in implementing e-assessments reveals that the development of ICTs can alter learning assessment in terms of, namely:

- Making assessment continuous and accessible: Regardless the scale and duration of disruption of learning in brick and mortar schools, e-assessment can be conducted anywhere, allowing students to practice and receive prompt feedback in and outside of an allocated time.

- Making assessment more authentic (by teaching learners more mental resilience to changes in study, work and life): Essentially, e-assessment can assist teachers to diagnose students’ learning gaps and drive personalised learning through the provision of timely and relevant student feedback, thus helping them achieve learning goals.

- Making assessment automated: AI-assisted marking helps reduce teachers’ workloads, as they often deal with grading hundreds of test or exam papers weekly and are often under time pressure. This innovation may remove human biases while maintaining comparability of scores with those graded manually. However, the process should be supervised by humans to ensure that fairness is carried out during the exam.

- Enlarging the curriculum scope: There is a link between system approaches for e-assessment and pedagogical implications. Thus, the integration of ICT in education with learning assessments provides possibilities for expanding the knowledge content that exists in textbooks, requiring learners to adapt to lifelong learning.

Thank you. I’m curious to know how the evidence from this rapid review of country experiences in implementing e-assessments leads to the conclusion – apart from in a propositional sense – that ‘the integration of ICT in education with learning assessments provides possibilities for expanding the knowledge content that exists in textbooks, requiring learners to adapt to lifelong learning’.