This article was written by Raymond Douse who co-founded Whizz Education over 15 years ago and has been a Director of Whizz since. It was originally published on 8 April as part of the Whizz Insights April 2020 edition, which focused on the COVID-19 pandemic and can be found on the Whizz Education website.

The coronavirus pandemic has, according to UNESCO, so far caused 188 countries to implement nationwide closures of schools and universities, and several others to close educational facilities on a localized basis. More than 1.5 billion learners, representing over 91% of those enrolled, have been affected. The closures began at the end of January, increased before the end of February, and progressively accelerated during March.

UNESCO believe that the policy response in all countries so far has emphasised avoiding the disruption of learning, to the extent possible, by the scaling up of radio and television delivered lessons, online educational services and the use of applications to support communication with learners and parents. Interactive online services clearly have the most potential to best simulate the school experience and are being deployed widely.

However, the SDG-Education 2030 Steering Committee at its emergency meeting on April 2nd has brought an important focus to the education world’s thinking by urging that:

- Inclusion and equity should be the guiding principle of all COVID-19 education responses;

- The critical roles that teachers play in the COVID-19 response and recovery should be recognised and supported;

- Adequate political commitment and investment in education in the recovery phase needs to be ensured

Regrettably, even in the rich countries, closure of public libraries and other meeting places has served to exacerbate the digital divide between those students able to access remote learning applications at home and those without the necessary facilities. This inequity between students is greatly magnified in the less rich countries. Indeed, the most under-privileged live in areas without even electricity, let alone computers and adequate Internet connectivity.

Given that good low-cost distance learning solutions are available now in many countries and languages, it is to be hoped that more governments will initiate and fund the distribution to their low income families of both computers and WiFi hotspots. Countries like Estonia and Cuba pioneered WiFi hotspots for students seven or more years ago but it has taken the coronavirus crisis to encourage, for example, the Municipality of Amsterdam in the Netherlands and a plethora of U.S. municipalities, not to mention Google in California, recently to announce funding programmes for computers and WiFi hotspots for students from poorer households in their regions. In some U.S. states, WiFi equipped school buses are also being deployed to support disadvantaged students. In the UAE, the Government is providing free mobile internet access to households without a fixed home connection.

The quality of teacher-driven remote learning initiatives will, of course, vary a lot with the experience of the teachers concerned in delivering instruction online. Many well-practiced technology-oriented teachers nevertheless caution against attempting too frequent synchronous video conferences. The dynamics of one-to-many teaching in a physical classroom differ dramatically from a Zoom based interchange with 25 students of whatever age. “I Zoom with small groups,” a New York pre-K teacher is quoted as saying. “They’re three and four — the mute button on Zoom? I mean, come on!”. Zoom is also having to scramble to allay privacy and security concerns. Meanwhile, teachers realise that grading students working remotely from home becomes highly problematic when the comparative conditions under which different students are working at home cannot be known to them.

By contrast, some adaptive online tutoring applications like Maths-Whizz® are able both to personalise the delivery of Maths teaching and practice to each individual student and, through their continuous assessment functionality, constantly update the student’s Maths Age™. Furthermore, the teachers in schools deploying Maths-Whizz see real time reports of all of each student’s activity on the programme, enabling a “flipped classroom” approach in which the teachers can concentrate on individual conversations with the students whether through Maths-Whizz’s messaging or by Skype or Facetime. If the teacher still wants a Zoom call with all of the class for social purposes, he or she can always use an activity from the Maths-Whizz whole class teaching resources as a centrepiece for, say, a problem-solving discussion.

Whizz Education has sought, during school closures, to support both its school and parental customers worldwide in student use of Maths-Whizz at home with webinars, other online support and individual guidance from its Education Success Partners. The students in our UK schools have, on average, increased their time spent using Maths-Whizz by 50% between the last week of February and the last week of March. We have seen similar increases among international school customers in Mexico City and Nairobi and in U.S. schools in states such as Kentucky and Washington. All these schools are achieving usage rates that we have traditionally seen, even before school closures, in New Zealand and Thailand.

The corollary of these usage levels is that the students concerned are able to demonstrate to their teachers that, on average, they are mastering 2 to 4 new learning objectives per week, and continuing to progress at the expected pace through the Maths curriculum despite the distractions of the pandemic. This strongly suggests that with careful planning, support for teachers and the parental engagement encouraged by the parent dashboard, Maths-Whizz can play a vital role in safeguarding student learning in maths during these disrupted times.

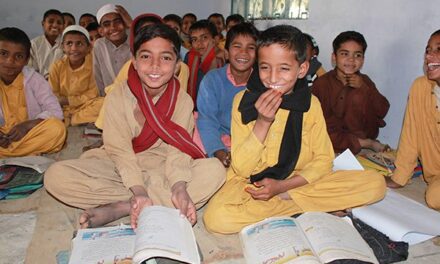

Whizz Education much regrets that, by contrast, at its projects in rural counties of Kenya and Mexico, school closures largely mean that students are not able to access Maths-Whizz for lack of a computer and an Internet connection at home. Students here may also be suffering the additional adverse consequences of school closures noted by UNESCO such as lost access to a nutritious midday meal.

As a global education partner, we are developing plans to support students in less developed parts of the world as part of our commitment to sustain learning outcomes. This includes enhancing Maths-Whizz to become better compatible with mobile Smartphones given that there is a high penetration of low-cost smart phones even in less developed parts of the world (Kenya’s penetration rate of mobile Internet users is at 83%). In addition, we are producing a suite of pedagogically sound ‘flat’ maths content for students in the form of dynamic worksheets and exercises that can be readily accessed from a smartphone with limited data burden and providing support to teachers through WhatsApp.

“A child’s right to an education does not change because of a crisis. In fact, it is just as important as every other need, and can even improve outcomes in other sectors”, according to UNICEF Executive Director, Henrietta H. Fore. With this in mind we are constantly evolving our education response during this outbreak and will continue to support schools, teacher and parents to sustain learning to the best of their ability. We call on the education sector to share your responses to the Covid-19 outbreak so that we can learn from each other to support learning and help to make sure that no child is left behind during this challenging time.