This blog was written by John Deans, Director of Oriel Square Ltd. This was originally published on the Oriel Square website on 26 June 2020. Following the Department for Education’s ‘catch up’ funding announcements, John considers how these months might widen the attainment gap; and asks whether emergency funding for schools addresses the problem.

Everyone is aware of the different lived experiences the national reaction to Covid-19 has brought. Even without looking beyond our own families or groups of friends, we see how the national reaction to the epidemic has become a magnifier of small difference: difference of age, physical and mental health, financial security, quality of housing, family status, and so on and on. In the national public conversation about these varied experiences in the face of restrictions, there has been a big focus on children and on education. (Everyday conversation in my circle often lights on the practical difficulties of childcare and homeschooling: parents envy the carefree, kidfree summer of endless mint juleps and relaxed garden reading they imagine for those of us without these responsibilities.)

School classrooms began to thin in the week before we entered lockdown, as among those parents who could, many began to keep their children at home; within days, some schools were closed entirely, and all but the children of key workers and those with other identified needs were at home.

Widening gaps

For those of us in education, our biggest concern must surely be the magnification of the attainment gap. At Oriel Square we are proud of the work we did with OUP two years ago to produce an Oxford Language Report which discussed the now well-understood word gap that opens up in children’s first years and widens as they grow. But differences of background and cultural expectation affect young people’s development and life chances right through their education, and all risk being widened. For example, will the regression some fear working-age women are already suffering at home and in the workplace – and balancing the two – have an effect on the outlook of, and choices made by, girls at school?

The different levels of access during the crisis to education for children according to school and family situation are now very well known: an average of 2.5 hours’ schooling for those not in class, and vastly varying quality of online and offline access to learning for those children (see the UCL Institute of Education paper from two weeks ago). In May, the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance calculated that undoing the increased impact of one month’s shutdown on students in KS2 alone would be £3.4bn. While that sounds like a huge amount of money, it can be compared to the £60 billion government expects to pay to protect jobs and businesses through the furlough scheme.

Government response

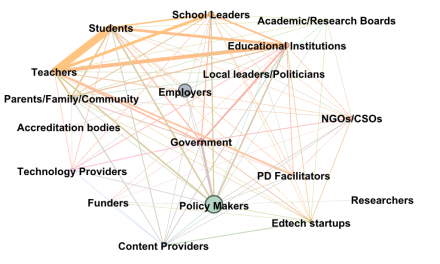

Last week, the Department for Education announced an additional £1bn in funding to English schools for ‘catch-up’. This includes £350mn for a National Tutoring Programme, administered by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), Sutton Trust, Impetus and Nesta. The intention is to give support to disadvantaged students in schools (likely those who attract the Pupil Premium), either through heavily subsidised access to existing (external) tutorial businesses, or through specifically trained graduates who will provide intensive in-school catch-up support for groups of students during lesson time.

There remains less clarity over the announcement of the remaining £650mn. Initial indications that it would be available to spend on catch-up summer schools, recruitment or IT infrastructure seem to have been contradicted. Although it first seemed the money would be dispensed as grants that would be applied for, it now appears that the money will be distributed on a strictly per-pupil basis; but that schools will have a large degree of discretion in deciding how it can be spent.

The DfE continues to fund the Oak National Academy, which is currently engaged in (very quickly!) creating a detailed curriculum map for the whole 20–21 school year, at every age level (from Reception) across core curriculum subjects. The majority of the whole year’s resources are promised in time for the start of the year. With the weight of the DfE behind it, there’s some risk that this particular curriculum interpretation becomes a de-facto requirement in schools. This has happened in the past with similar initiatives, for example, the ‘Sample Medium-Term Plans’ around the National Strategies (despite the pretty clear signalling in the name). It’s to be expected, therefore, that providers of resources will work to make them as easy as possible to run alongside this mapping.

This ongoing investment in, and activity by, the Oak National Academy can be seen as contingency planning for an incomplete English school return in September. It is certain that reliable and consistent provision will help to compensate for a disrupted schooling environment.

Beyond the spread of the Oak

The provisions discussed so far apply only to school-age children, whereas it’s in younger children that the divergences begin to open up which lead to big differences in educational outcomes a few short years later. It’s much to be hoped that this will be addressed over the coming months; in the meantime, initiatives like the BBC’s Tiny Happy People offer useful resources to the parents of these younger children; when they can be reached.

Looking at the amount of money being spent against the estimated need, and at the level of targeting of that spend, the government’s reaction so far feels like the initial fire-fighting phase. But as we know too well, the chance to make a difference in the lives of those children vulnerable to falling behind passes very quickly.