This blog was written by Professor Pauline Rose, Director of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge. It was originally published on the CAMFED website on 3 November 2021.

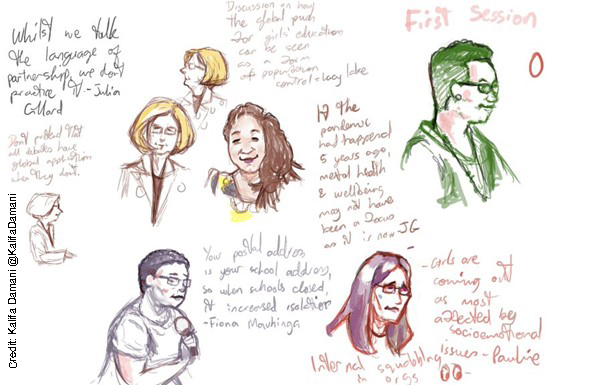

Together with the Yidan Prize Foundation and CAMFED (the Campaign for Female Education), we hosted a conference in Cambridge on 7th October 2021: Creating an Equitable Future Through Education. At the international event, we announced a new partnership with CAMFED to examine how community-led interventions that target the needs of the most marginalised children can be scaled through education systems in Tanzania and in other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. This research aligns well with the conference theme of creating an equitable future, and some of the related issues are highlighted in this blog.

The conference opened with a keynote speech from the Honourable Julia Gillard, who stressed that we need “a revolution in data” and to imagine a world where everyone has access to real time and comparable quality education data. “Transparent data makes people accountable. … Because we are data nerds, we are very hard wired to let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Yes, it is impossible to get perfect education data each time and every time but we can get and should be able to get at least one galvanising metric that we can look at globally to help us inspire change.”

This was followed by Julia Gillard discussing advancements and challenges in girls’ education in the context of COVID-19 and climate change disruptions in conversation with Lucy Lake and Angeline Murimirwa from CAMFED – who were both 2020 laureates of the Yidan Prize for Education Development.

Taking these discussions further, I was delighted to have the opportunity to be part of a panel discussion focusing on inclusive education in the context of disruption, along with Fiona Mavhinga, CAMFED; Alicia Herbert, FCDO; and moderated by Andrew Jack, Financial Times.

We noted that one of the positive outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the collaboration and speed with which evidence and data has been generated to inform policy and practice within countries and globally.

Around the world, schools closed from March 2020 – usually for at least a school year, often more (with some only just re-opening, or countries like Uganda predicting not to open until January 2022). Drawing on data and evidence emerging from low- and lower-middle income countries, I highlighted the following key effects of these school closures on education in low- and lower-middle income countries:

Dropout from school

Perhaps encouragingly, the impact of school closures due to the pandemic on dropout might be lower than feared. In Ethiopia, we find that around 13% of primary school children were not returning to school. Analysis by the Center for Global Development similarly finds dropout rates to be relatively low also in Ghana. Even so, the number is sizeable. And, in Ethiopia, we find that girls, older pupils and low performers in 2019 were significantly more likely than their peers to drop out of school.

Similarly, the Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence (GAGE) programme reports an increase in adolescent pregnancies, and that many girls are also marrying younger, both of which could increase the likelihood of them dropping out from school.

In addition, while children might appear on the books as enrolling when schools initially re-opened, there is a danger that children might not be able to attend school regularly, and could still drop out.

Global learning loss estimates

One particularly alarming aspect of the pandemic is the adverse effects on learning. As a result of school closures, the World Bank estimate that the pandemic will push 72 more million children into learning poverty – meaning that they are unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10.

Simulations by colleagues in the Research for Improving Systems of Education (RISE) programme further identify that, without mitigation, children could lose more than a full year’s worth of learning from a three-month school closure because they will be behind the curriculum when they re-enter school and will fall further behind as time goes on. They raise concerns that those in lower grades could be particularly affected.

Learning inequalities

Our research for the RISE programme in Ethiopia has further highlighted that school closures are reinforcing inequalities. We find that children in Grade 4 before the pandemic who live in urban areas only progressed at less than half of the speed that would have been expected once schools re-opened. And progress was even lower for rural students, whose learning progressed by only one third.

A reason for the uneven effects of learning loss is due to inequality in access to technology and other support to children’s learning during school closures, particularly for children from poorer families and those in rural areas. Millions of children have had no access to remote learning – in Uganda, home internet connectivity “is the lowest on the planet at about 0.3%”. We found something similar in Ethiopia, where access to the internet is negligible, including for teachers, with only 1 in 10 rural teachers having access.

Even access to more basic technology is limited, with inequalities in access. For example, in Ethiopia we find that only around half of rural households had access to radio (the medium through which education programmes were delivered during school closures to primary school children).

The GAGE programme further identifies that girls’ access to technology and phones in Ethiopia is very limited. They can sometimes only access these through males in their families. UNICEF reports this to be similar in India – with girls less likely to have more sophisticated technology tools.

Evidence also identifies that girls had increased domestic responsibilities during school closures, limiting their opportunity to learn at home. According to Young Lives, in Ethiopia, 70% of young women spent more time on household work during lockdown, compared to only 26% of young men. A sobering study by Echidna Giving of nearly 400 of the hardest-to-reach rural adolescent girls in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda found that 34 percent had lost a parent or guardian to COVID-19, 70 percent had to pursue income-generating activities, and 86 percent could not afford to return to school.

An increasing body of evidence has documented the negative impact of COVID-19 on students’ academic learning, which is likely to extend beyond the crisis. Less attention has been given to the important role of students’ socio-emotional learning (SEL), mental health, and wellbeing. Our ongoing research in Ethiopia shows that focusing only on students’ numeracy and literacy—while no doubt important—limits our ability to achieve a more holistic understanding of students’ learning and development.

Future looking

As schools re-open and countries make efforts to catch up on learning, evidence is emerging that allows ‘data nerds’ to provide vital information in a timely fashion for action. This evidence highlights several issues that deserve attention in tackling the ongoing effects of the pandemic:

- We need to continue to keep track of dropout and learning loss levels – disaggregating this for different population groups (including by gender, wealth, rural/urban location, and disability), and swiftly take any necessary actions to target support to particular groups.

- We need to assess learning more holistically, including mental health and wellbeing, along with academic outcomes (such as related to literacy and numeracy).

- Barriers for pregnant school girls need to be removed urgently so that they can re-enter schools.

- Teachers’ own wellbeing needs to be taken into consideration, especially of female teachers who have been supporting marginalised girls within communities.

- Education needs investment now more than ever! This is not a time to cut budgets to the poorest countries and most marginalised students who are already struggling with access to learning.