This article was written by David Masua, Ian Leggett and Rodrick Hicks, Windle Trust International (WTI).

The Covid-19 pandemic led governments across the world to close schools for many months as one measure to control the spread of the virus. Millions of children were affected by these school closures, and their prolonged duration has prompted widespread consideration of how best to make up for the teaching and learning that has been lost. Evidence from East Africa suggests that technology-based catch-up programmes are simply not reaching children from poor families or areas with no basic services. In this way, existing inequalities have increased with the digital divide overlaying the poverty divide and reinforced by geographical marginalisation of remote rural areas.

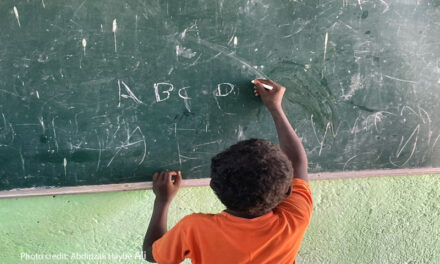

The experience of Windle Trust International (WTI) in South Sudan illustrates that alternative approaches are viable, effective and more appropriate to the economic, social and technological context. It provides evidence of the potential to devise and scale up catch-up programmes that will support those who have missed out due to prolonged school closures. Instead of relying on technology and infrastructure, which is often non-existent, WTI developed a programme based on accelerated learning that was specifically designed to reach those who have dropped out of secondary schools or who failed to make the transition to secondary education.

Instead of being seen primarily as a short-term response to a humanitarian crisis, such as war or disease, WTI believes that accelerated learning programmes should be designed and developed to address disruption to education provision rooted in and made worse by social and economic inequalities and marginalisation.

Our new report draws a distinction between catch-up and accelerated secondary programmes. The former is short term and designed to help children get back into formal school; the programme will be adjusted according to the extent of learning loss that has occurred. An accelerated programme, in contrast, is designed for those whose education has been interrupted and who cannot, or are unlikely to, re-enter conventional schooling.

Our new report draws a distinction between catch-up and accelerated secondary programmes. The former is short term and designed to help children get back into formal school; the programme will be adjusted according to the extent of learning loss that has occurred. An accelerated programme, in contrast, is designed for those whose education has been interrupted and who cannot, or are unlikely to, re-enter conventional schooling.

The report sets out some of the salient features that influence access to, and the quality of, education in South Sudan before going on to describe an innovative Accelerated Secondary Education Programme (ASEP). Although that programme reflects the particular needs of education provision in one country, the issues it seeks to address will be found to a greater or lesser extent in many others. The principles of accelerated learning are well-established, but the South Sudan programme is distinctive in two ways; first, its focus is on secondary education; secondly, it has been designed to meet the needs of two quite different target groups within the population.

One target group was existing untrained primary school teachers. Usually, they have been teaching for several years but since they do not have a secondary school leaving certificate, they are not eligible for further training. In 2019, the Accelerated Secondary Education Programme (ASEP) was recognised as a practicable and cost-effective way of improving the quality of education in primary schools and of increasing the motivation of untrained teachers.

The second target group was young women who have dropped out of school. Some may have dropped out of school due to forced marriage, pregnancy, family poverty and the need for labour at home or, more recently, as a result of school closures. In South Sudan – as elsewhere – if girls and young women drop out of schooling either at the end of the primary stage or during secondary education it is almost impossible for them to ‘drop back in’ into full time education in future years. There are few ‘second chances’ in a country with such limited education resources such as South Sudan. The Covid-19 induced school closures will have greatly increased the number of girls who now fit into this target group as while schools were closed they will have been pressured into becoming an economic asset, either due to their labour in the community setting or due to their marriageability.

The paper sets out the key features of the ASE programme such as eligibility, selection criteria and course structure. It also emphasises the over-riding importance of working in close partnership with the Ministry of Education and of developing a programme that would complement and not compete with or weaken existing secondary school provision. Finally, the paper concludes by assessing the compatibility of the ASEP programme with the key principles of the UNHCR-led accelerated education working group (AEWG).