This blog was written by: Monazza Aslam (OPERA), Phoebe Downing (REAL Centre, University of Cambridge), Romanshi Gupta (Tetra Tech), Shenila Rawal (OPERA), Pauline Rose (REAL Centre, University of Cambridge) and Katie Stewart (Tetra Tech).

Improving the quality of teaching through interventions that enhance pedagogy and support teachers in delivering learning is vital for increasing educational outcomes. This is one of the intended outcomes of the Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC), funded by the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), that has been in operation since 2012.

This blog highlights some of the key findings from our upcoming study focusing on how four selected projects in the second phase of the GEC (GEC II) have engaged teachers and sought to improve teaching quality, with a particular focus on marginalised girls’ education. We focus here on how four GEC projects have adapted their interventions or introduced new ones during the COVID-19 pandemic to support girls to continue learning.

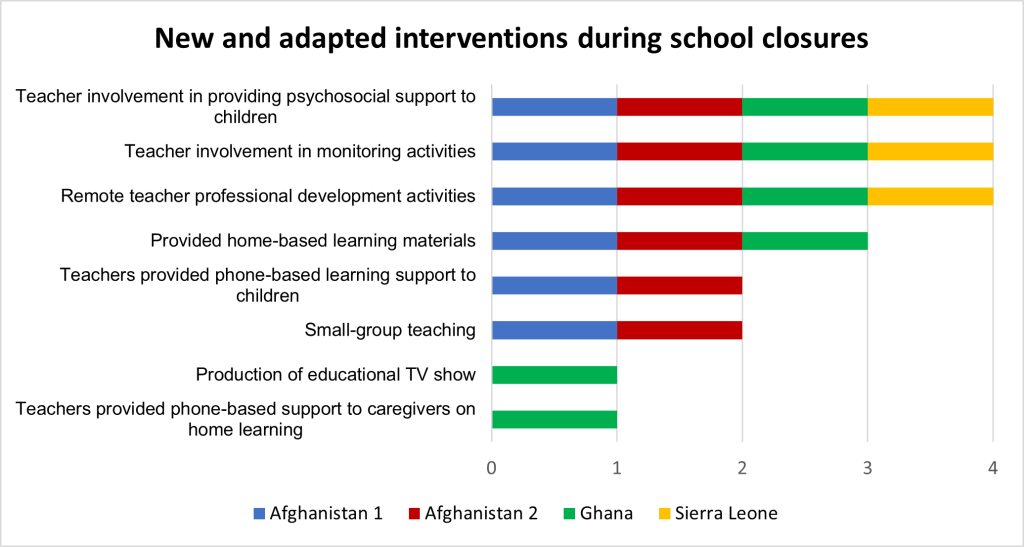

These four projects operate in Afghanistan, Ghana and Sierra Leone. As elsewhere around the world, schools in these countries were closed from March/April 2020, and started to re-open in a phased manner from July 2020. As shown in the figure below, teachers took on new psychosocial wellbeing and monitoring roles across all the four projects. However, the nature of the interventions varied, as outlined below.

Teaching adapted to remote learning approaches

During school closures, all four projects were able to draw on existing project infrastructure to adapt their interventions aimed at improving the quality of teaching in order to provide remote education. This included teachers answering students’ questions or monitoring their learning via telephone calls (and for one project, phoning their caregivers); in-person small group sessions in villages by project-employed teachers; and the provision of home learning materials such as textbooks and assignments. One project catering to out-of-school girls paused the provision as home-based learning came with challenges, such as girls’ low literacy levels and lack of access to technology. However the female mentors continued to provide girls with informal and pastoral support during this period.

Across the projects, learners were generally positive about continued engagement with learning and contact with teachers during school closures.

| ‘I felt really happy and [my mentor] encouraged us that we should continue studying what they taught us when the Safe Space was open. Every night, I try to read and think about everything they have taught us at the Safe Space.’ (Female learner, Sierra Leone) |

However, some girls faced particular challenges, including poor access to technology, increased domestic responsibilities (including both domestic chores and agricultural responsibilities), inadequate resources at home (such as textbooks or assignments) and limited avenues for feedback from teachers or caregivers. After schools had reopened, some girls indicated that they preferred learning at home in circumstances where there were school resource constraints, inadequate classroom infrastructure, safety concerns, or they faced a long distance to school.

Teachers’ roles expanded to include wellbeing support to students

During school closures, teachers were on the frontline to provide both continued or adapted learning opportunities, as well as vital health and safety or psychosocial and wellbeing information and support to students. Female community-based educators were instrumental in monitoring girls’ wellbeing and mitigating their risk of dropping out. Teacher engagement was particularly valuable to communities and parents with low literacy levels in encouraging girls’ return to school after reopening.

Teacher professional development continued

All four of the projects attempted to continue some form of teacher professional development during the pandemic. They adapted training content and modes of delivery to reflect changing learning needs. Teachers generally found the training satisfying, particularly in developing their overall teaching methods and subject knowledge, their ability to support marginalised girls to come to school, and their access to teaching materials and learning resources.

| ‘Being a teacher is an art, [we] must teach students in every possible way. And these projects helped us become…artists, to teach students in a better way because when we graduate from university, we have no experience and [now] we gain little, little experience and skills.’ (Male teacher, Afghanistan) |

However, teachers from all four projects cited a need for higher remuneration, more material support and longer or more sustained school-based training.

Catch-up lessons introduced after schools reopened

All four projects made changes to teaching and learning activities to accommodate the need for remedial/catch-up lessons after schools reopened. Learners reported mixed perspectives on remedial lessons/catch-up strategies – useful practices included repetition of content that was taught prior to the pandemic and teachers checking for learners’ understanding, while less helpful practices included focusing on new content without reviewing previous content.

The pandemic has shown more than ever that teachers play a vital role in supporting students, and that their work goes beyond teaching in the classroom. The emerging findings from our study highlight the need to provide teachers with appropriate support to manage their own wellbeing whilst enabling them to fulfil their responsibilities.

The full findings and recommendations from our study exploring how GEC II projects have implemented and adapted interventions with teachers and teaching before and during COVID-19 will be published in the coming months. Watch this space!

See also information about resources on teaching during COVID-19 developed by the Girls’ Education Challenge.