This blog was written by Stephen Bayley, Darge Wole Meshesha, Paul Ramchandani, Pauline Rose, Tassew Woldehanna, and Louise Yorke. It was originally published on the RISE Programme website on 7 December 2021.

Research has begun to quantify the extent of learning loss following school closures, with many studies focusing on academic learning. However, evidence often overlooks the effects of the pandemic on children’s learning more broadly, including the effects of socio-emotional learning and the link with mental health and wellbeing.

Prolonged school closures since 2020 as a result of COVID-19 have prompted global concerns about the impact on children’s learning, particularly for the most marginalised. As a result, research efforts have begun to quantify the extent of learning loss to inform national education programming to support all pupils as schools have reopened. Many of these studies focus on academic learning, particularly with respect to literacy and numeracy. However, evidence often overlooks the effects of the pandemic on children’s learning more broadly, including the effects of socio-emotional learning (SEL), meaning children’s social skills and emotional interactions. There is also very limited evidence on the link between SEL and mental health and wellbeing.

To address this, our new Working Paper, Socio-Emotional and Academic Learning Before and After COVID-19 School Closures: Evidence From Ethiopia, examines the effects of COVID-19 school closures on children’s holistic learning, including both socio-emotional and academic learning. We summarise key findings and recommendations from this paper below.

Social skills have declined following COVID-19 school closures, especially among rural learners.

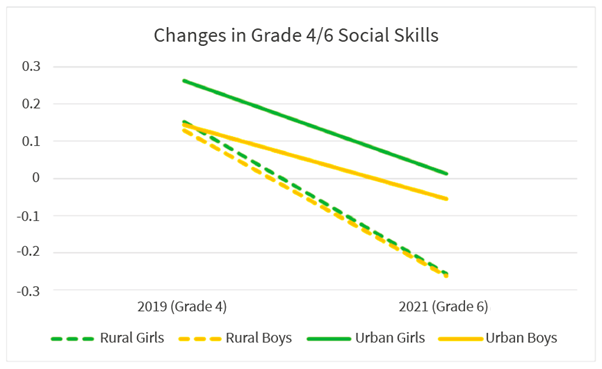

Drawing on data collected in 2019 (prior to the pandemic) and 2021 (after schools re-opened) to compare primary pupils’ learning before and after the school closures, Figure 1 shows trends in social skills for learners surveyed, disaggregated by gender and location. Social skills were measured by children reporting their likelihood of sharing things with others, confidence in talking to others, and ease of making friends, for example.

Rural and urban boys and rural girls started at a similar point in 2019, with only urban girls reporting noticeably higher levels of social skills before the school closures. Over time, however, there is a statistically significant decline in social skills for all pupils. Although all groups show a decrease in social skills, the decline is steepest for girls and boys in rural settings, suggesting greatest losses among rural children.

In summary, our data show that social skills have declined between 2019 and 2021 and following the COVID-19 school closures, with the greatest reductions among rural children. All of this highlights the need to promote social skills in addition to academic learning in response to COVID-19 and other major crises, with a particular focus on rural areas.

There is a positive and significant relationship between children’s social skills and their numeracy.

In addition to the decline in social skills, we find that numeracy gains fall short of the forecast trajectories for children’s learning before school closures, particularly for those in rural areas. Looking at the relationship between social skills and numeracy, our analysis shows a strong, positive association between these, even after controlling for different child, school and household factors. Children achieving high scores in the 2021 numeracy assessments also reported more advanced social skills.

Children’s social skills are positively associated with their mental health and wellbeing.

Our findings show that children’s social skills are strongly associated with their mental health and wellbeing. Concerns about children’s mental health and wellbeing have risen to the fore following the COVID-19 school closures, when many learners have been isolated from their peers. Evidence from Ethiopia, and more widely, suggests growing mental health issues among children as a result of the pandemic. At a time when schools have re-opened but the ongoing pandemic continues to affect education and create uncertainty, these findings highlight the need for education provision to support wider learning and children’s welfare.

Our research shows the interconnected and interdependent nature of children’s learning, which highlights the value of a more holistic definition of ‘learning’.

A key finding of the research concerns the interdependency and interconnectedness of children’s SEL and their academic learning, as evidenced by the strong and positive relationship between Ethiopian pupils’ social skills and their numeracy, as well as between social skills and mental health and wellbeing. This indicates that SEL must be addressed in conjunction with academic learning. Interpersonal interactions are important for safeguarding children’s holistic welfare.

Education planners, teachers, headteachers and other stakeholders, such as parents and guardians, need to find solutions to embed and support SEL throughout children’s school careers and beyond. Based on the analysis, we recommend strategies for mainstreaming SEL within schools. Particular strategies should ensure that they are relevant for those living in rural areas, and could include:

- establishing a dedicated office with appropriate expertise, preferably at school level but at least at woreda [district] level, to develop approaches for mainstreaming SEL within education, including during crises and closures;

- designing and implementing specialised teacher training programmes, both for pre-service and in-service participants, to share practical pedagogies and methods for promoting SEL;

- reviewing curricula, syllabi and related documents to ensure that they are aligned with teaching approaches to foster SEL throughout primary and secondary education;

- committing additional resources to timetabled extra-curricular activities that nurture SEL, for example through school clubs, ideally also taking place during the vacations;

- Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health, together with aid donors, working more closely together to target funding and support to foster SEL and positive mental health and wellbeing among the most marginalised children.

We are grateful to the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) programme and the LEGO Foundation for funding this study.