This blog was written by Susannah Hares, Co-Director of Education Policy and Senior Policy Fellow, Center for Global Development (CGDev), and Professor Pauline Rose, Director of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge. It was originally published on the CGDev website on 23 April 2021.

2021 was to be the year in which the UK took leadership of global education. So it’s devastating that, instead of demonstrating its commitment to education during this moment in the spotlight, the UK government has chosen to cut education spending by more than 40 percent, compared with overall aid cuts of around 25 percent.

The UK chairs the G7 this year. The government has committed to using the platform to boost global education. Later in the summer, prime minister Boris Johnson, alongside Uhuru Kenyatta, the president of Kenya, will chair the replenishment of the Global Partnership for Education, a key moment for the global community to come together to support education for every child, everywhere. Both summits take place against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disrupted education for children in almost every country, and will constrain domestic education resources in some of the poorest countries.

The cuts announced this week show that the UK government’s ambitions and rhetoric on education are not matched by its actions.

The UK is one of the largest donors to basic education

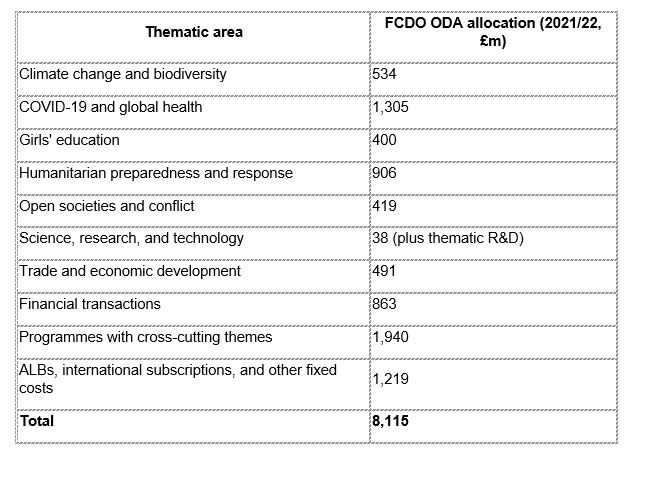

The UK is one of the most generous donors to education and is the second highest bilateral donor to basic education (figure 1).

Figure 1. Average annual disbursements to education over 2017-2019 (GBP billions, constant 2018). Source: authors’ analysis of OECD-CRS. Note: shown for bilateral donors that disburse >2% of annual bilateral average over period 2017-2019. Sorted by total contribution to Basic. “General” includes teacher training, education facilities and training, educational research and education policy & administrative management.

The UK generally spends education aid well. Aid is targeted toward countries with high need, with Pakistan, Ethiopia, Nigeria being large recipients of education money and countries with among the highest numbers of children out of school. The UK is already an influential actor in the global education aid architecture, and wants to further increase its influence in domestic policy, using its diplomatic network, the cutting edge research it generates, and its skilled cadre of advisers. Cutting aid to education could undermine the government’s efforts to influence developing country partners to prioritize education as well as its efforts to fundraise for the Global Partnership for Education.

Smoke and mirrors hide the education cuts

On Wednesday, the UK foreign secretary Dominic Raab announced that the FCDO will spend £400 million on girls’ education in 2021. Unpacking what’s behind that figure, and how it compares with previous years’ spending, requires some detective work.

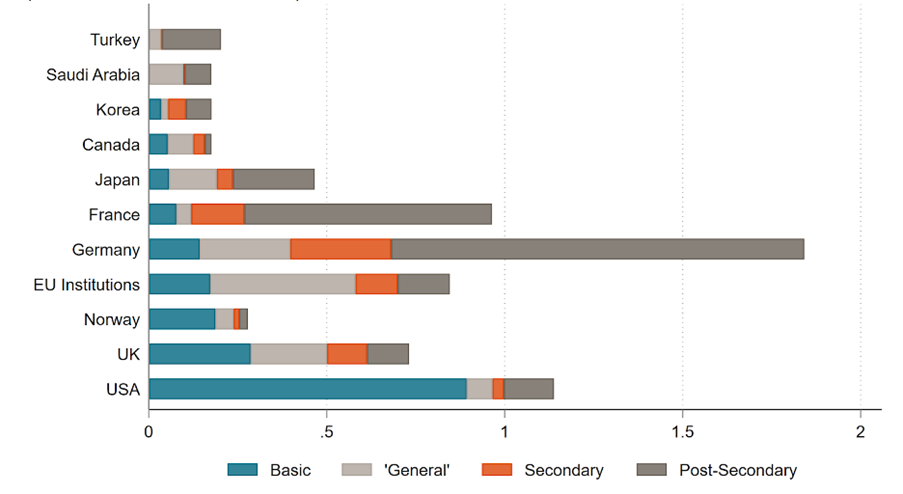

The foreign secretary’s statement provided the total allocation for 2021 by “thematic area” (table 1), which are not existing categories in UK aid spending. This lack of transparency makes it challenging to compare 2021 allocations with previous years. Our analysis suggests that the £400 million commitment to girls’ education comprises all planned spending by the FCDO on education, including any disbursements to the Global Partnership for Education in 2021 (Global Partnership for Education disbursements are included in official bilateral spending figures). It is important that the FCDO clarifies this assumption.

Table 1. Thematic allocation of UK aid money 2021. Source: https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2021-04-21/hcws935

The 2021 allocation to education is a 40 percent drop on previous years

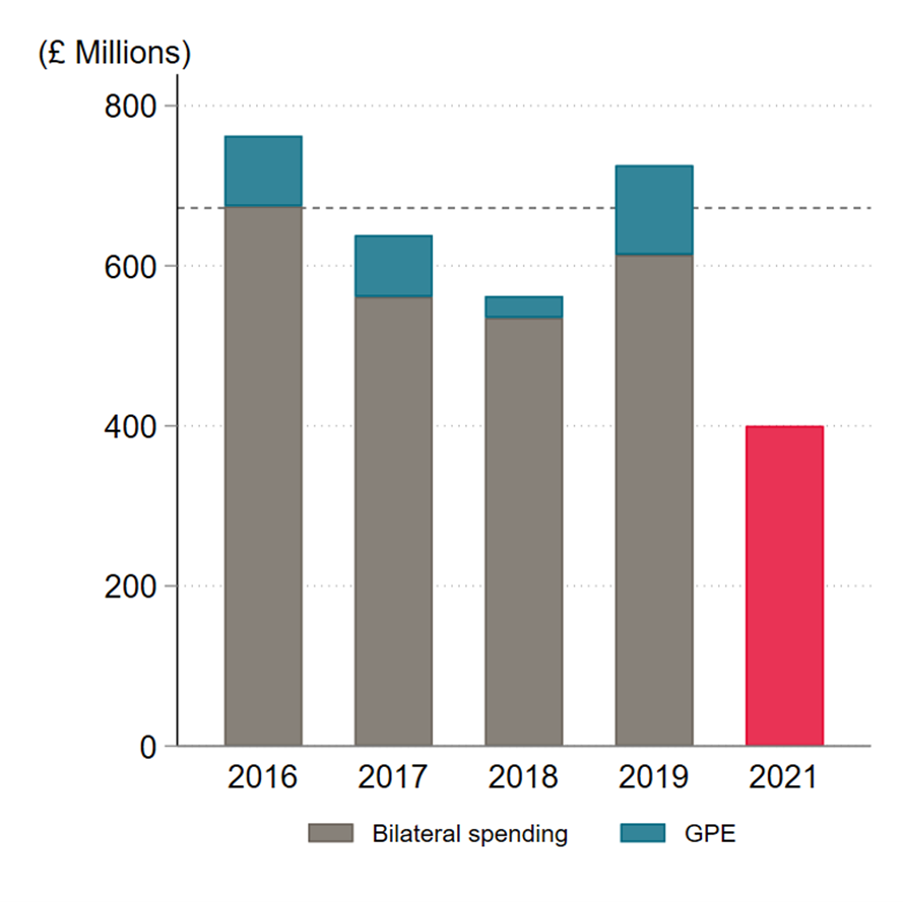

To compare this year’s commitment with previous years, we have analysed bilateral spending by the FCDO (DFID) on education and its contributions to the Global Partnership for Education for the last four years, for which we have complete spending data. The average annual spend by FCDO since 2016 was £672million per year (figure 2). The 2021 commitment of £400 million, therefore, represents a cut of more than 40 percent of the four-year average, and close to 50 percent of the last year (2019/2020) for which we have full spending data’s spend.

Figure 2. FCDO / DFID spending on bilateral education and GPE. Source: authors’ analysis of IATI data and the Foreign Secretary’s statement to Parliament 21st April 2021. Dotted line is four-year average spend.

These cuts will be catastrophic for children in some of the poorest countries in the world

A couple of days after the UK asked world leaders to put their hands up and open their pockets for global education, it has slashed its own education aid. Education spending has been cut disproportionately to overall aid cuts (of around 25 percent), seriously undermining the UK’s leadership of the sector in this important year.

In the wake of a year of disruption for school children all over the world, with some children missing out on more than a sixth of their lifetime expected education, it’s simply devastating that the UK government has turned its back on its much-heralded commitment to global education. These cuts will have long-lasting consequences for education systems in some of the poorest countries in the world.

Thanks to Ana Minardi and Euan Ritchie for research assistance and to Sandra Baxter, Ranil Dissanayake and Ian Mitchell for helpful comments.