This blog was written by Vijay Siddharth Pillai, Education Program Manager with Street Child in Afghanistan. The author would like to thank Ramya Madhavan, Global Head of Education (Street Child), and Graciela Briceno for their support.

With an extended period of school closures in Afghanistan due to COVID-19 in 2020, the Ministry of Education decided to ensure continuity of learning through alternate means, including:

- lessons being broadcast via television and radio, and

- home-based learning through self-learning packages.

As the Ministry, along with development and humanitarian partners, engaged in the process of developing video and audio-based content, implementing partners in the Education in Emergencies Working Group (EiEWG) decided to provide support to children who don’t have access to devices/services. Given that only a small proportion of learners have access to the internet or necessary devices for accessing digital content, self-instructional material for Grades 1-3 was developed to supplement the textbooks and ensure that the education sector’s response to COVID-19 remained inclusive.

The Ministry of Public Health recently detected a third wave of the virus in Afghanistan, which has led to closure of schools in many provinces. Therefore, it is an apt time to evaluate the self-learning material developed last year, before it is considered for redeployment as part of the emergency response during the third wave. It is important to recognize the emergency context in which self-learning packages were developed in Afghanistan. Unlike some other countries in South Asia, the EiEWG made a credible attempt to ensure that the response from the education sector was inclusive through a no-tech approach. Yet the limited time and resources at the working group’s disposal did impede the further development or revision of self-learning packages.

This article aims to assess the resourcefulness of self-learning packages and make related recommendations to improve them. The resourcefulness of self-learning materials needs to be based on three aspects:

- how much of the resources are backed by strong evidence,

- how well do the resources scaffold implementation, and

- how well do the resources contribute to student self-learning.

Just like the shape of a cup provides clues to its intended use, curriculum material acts as an artefact with affordances and constraints to signal its intended use (Brown, 2009). An analysis of the affordances and constraints in the curriculum material does help us to understand its resourcefulness.

In classroom-based teaching, the teacher is considered as the central resource for learners. Understanding the diversity in the classroom, and to ensure learning occurs, the teacher packages and repackages content for students who may be at different learning levels and have different learning styles. Textbooks aid the teacher in this effort. In the absence of a teacher, traditional textbooks alone may fail to ensure active learning among children, as such books often focus on explanation of facts, concepts and theories. What is required in such situations is self-instructional material which not only provides information but also:

- defines what is to be learnt

- gives examples

- explains

- questions

- sets learning tasks

- answers learners’ questions

- allows learners to do self-assessment

- gives study advice.

Analysis of the design of self-learning material developed in Afghanistan

As part of the evaluation of the self-learning material, select mathematics modules from Grades 2 and 3 self-learning packages were analysed[i] – focusing on the structure, not content. Self-learning packages are generally structured as following:

- Introductory material: 1) Title, 2) Learning Objective

- Teaching and learning activities: 1) Explanatory text, 2) Assessment questions without feedback.

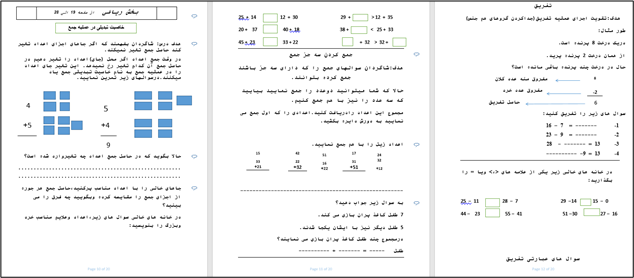

All the mathematics modules have a focus on assessment questions for students. In the introduction section, a stronger connection needs to be made between the current lessons and past learnings (see Figure 1). The structure of the self-learning material also shows certain variations from one package to another. The review process needs to ensure that all self-learning material has relevant explanatory text alongside, with assignment questions (one of the four modules which was evaluated did not have any explanatory text).

Figure 1: While the first lesson in the Grade 3 self-learning material provides a ready reference to the relevant page numbers in the Student Textbook, it begins by asking students “to remember their past lessons”, which does not facilitate the learner to connect the current lessons with the past learnings.

Figure 2: The Grade 3 self-learning material on mathematics poses many questions to be solved by learners with an absence of feedback on why certain answers(s) are correct and why certain answer(s) are incorrect. In the absence of clear linkages with student textbook, the explanatory text in the self-learning material is indispensable.

Some of the learning packages engage with visual aids to assist in knowledge acquisition and understanding, with a generous layout and illustrations, while some do not have clear topic headings. Transition phrases and verbal signposts need to be used more. Using several signposts in terms of topics, list of contents, headings, sub-headings, etc., helps the learner to negotiate a complicated learning unit. Including verbal signposts such as “in the next example we will show you…”, “in the last section…”, etc. helps to show interlinkages.’ Without such transition phrases and signposts, it becomes difficult for children to transition from one topic to another.

Figure 3: There needs to be a stronger focus on pre-requisite knowledge, transition phrases, verbal signposts and summaries in the self-learning material (Grade 2).

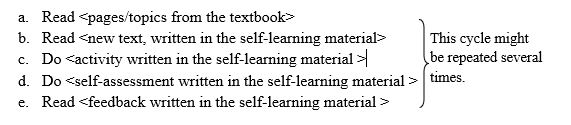

Three out of the four self-learning modules make a reference to the concerned pages in the textbook (as seen in Figure 1). However, this reference is only at the beginning of the module (Figure 1). There is a need to provide guidance to students on how to use the textbook alongside the self-learning material. One of the common ways to facilitate active self-learning is established by following the below-mentioned format

Without explicit linkages established between self-learning material and the textbook, it becomes difficult for students to use the textbook alongside the self-learning material. This is even more important if the self-learning material has negligible or no explanatory text to understand concepts.

Affordances for self-learning which need to be added into the self-learning material developed in Afghanistan

Unlike textbooks, self-learning material provides:

- guidance on how to study by oneself

- an adequate number and type of examples (especially if the textbook has only a few of them or if no references are made to the textbook)

- numerous activities for practice, application and analysis

- feedback on answers attempting to meet the need of all learners, assuming the student would have no support while he/she interacts with the material.

the above-mentioned four aspects. The packages need to provide a viable self-study plan for the learner. The materials also need to provide a prescribed time for the various academic tasks of each lesson, which could structure self-learning activities taking place at home.

Examples are critical when the learning goal is understanding and analysis (unlike gaining surface-level knowledge). They are most needed to aid in understanding and to develop proficiency in application of concepts, rules, principles and procedure. Examples are few in the self-learning material and those which are presented do not help the learner identify the rule from the example. For instance, while showing the example of addition of 2 digits in one of the modules, the example doesn’t show or explain the concept of carry over and just presents the final answer.

Figure 4: Unlike textbooks, self-learning material has to tell less and show more. Examples help in achieving this objective. They are critical to aid understanding and develop proficiency in the application of concepts, rules, principles and procedure. In this Grade 2 example, by simply providing a solution for the 2-digit addition, it does not help the learner to understand the rule or procedure.

Showing non-examples along with examples also helps the student in further understanding the procedure or rule related to the concept. For instance, to clarify the concept of a square, in addition to providing the picture of a square (example), it is better to provide also pictures of triangle and rectangle (non-examples) to discuss as to why these images do not fall into the definition of square. The same applied to the self-learning material being analysed here. For instance, as shown in Figure 5, while stating an example on how to measure the length of a pencil in one of the modules, the self-learning material could provide a non-example where the edge of the pencil doesn’t rest at ‘0 cm’ but at the edge of the scale leading to an error in measurement.

Figure 5: While examples are helpful as shown above, inclusion of non-examples provides further clarity (Snapshot from Grade 3, Set 5, Self-learning module)

While activities are the major focus of the self-learning modules, one of the significant steps which could be taken to improve the quality of the material is feedback on those activities. As tasks/activities provide feedback to learners about their progress and misconceptions, there should be several spread throughout the learning unit so that the feedback is continuous and immediate. This can ensure that misconceptions are not embedded deeper in learners’ minds by the end of the learning unit (which could happen if all tasks and feedbacks are placed at the end). Questions facilitating self-assessment should be followed by feedback. This feedback needs to provide the correct answer as well as comments on likely wrong answers.

There is ample scope for improvement of the feedback component on the assessment questions, which would provide more self-learning opportunities. In the absence of adequate parental or sibling support in households in Afghanistan, the student will not learn from these tasks unless the teacher spends considerable amount of time providing feedback during subsequent home visits. In short, if the student makes an attempt at the learning activities but does not receive immediate feedback, then the immediacy and substantiveness of the feedback is both lost – which is critical for learning. Substantive feedback not only reveals the correct answer but also explains reasons for it. It goes on to discuss the most common incorrect answers and why they are incorrect. It is in this aspect of effective self-learning material is substantially different from typical student textbooks by providing answers to learner’s questions.

Building Back Better – Review and revision of self-learning packages

It is truly commendable that the EiEWG-Afghanistan made a sincere attempt to come up with a no-tech response, unlike many other education clusters, in such a short time frame last year. However, there is merit in holding a comprehensive review of all of the 108 self-learning packages which were developed as part of the emergency response. The review and revision of these packages needs to ensure that the affordances for self-learning of various concepts are identified and embedded, keeping in mind the context of Afghanistan. This would not only prepare us to respond better in case of repeated school closures in the future but also can be creatively used in community-based face-to-face classes. If not, the self-learning packages will only contribute to some semblance of continuity of learning at home during school closures.

Note: More details about designing self-instructional materials, including best practices for writing and delivering educational content can be found in this free Commonwealth of Learning handbook: Creating Learning Materials for Open and Distance Learning: A Handbook for Authors and Instructional Designers.

[i] Self-learning packages which were evaluated were: 1) Self-Learning_CBE Grade 2_Months 4-6_Set 1_Dari 2) Self-Learning_CBE Grade 2_Months 1-3_Set 3_Dari 3) Self-Learning CBE_Grade 3_Months 4-6_ Set 5 4) Self-Learning – CBE- Grade3_ Months 1-3_ Set 1_Dari.