This blog was written by Kris Stutchbury (Senior Lecturer in Teacher Education), with contributions from Clare Woodward (Lecturer in International Education) at the Open University.

Nobody working in the field of international educational development would argue against ‘co-design’ as an aspiration for projects and resources. But despite all good intentions, the co-design process is not ideal: power is ultimately in the hands of the institution producing the resources, and feedback from the field on drafts is often limited, reflecting a power imbalance, unfamiliar ways of working and other pressures on people’s time.

The purpose of this blog is to highlight the issue of ‘co-design’ and to identify some of the questions and issues that it raises. This is particularly relevant now as the global pandemic of 2020/21 has created new opportunities for different types of collaboration.

The meaning of ‘decolonising’ is contested and varied but for many it means questioning and unpacking how colonial and hegemonic structures of power continue to produce inequalities, and reflecting on how unequal structures can be addressed. This means shifting from the historic model of North-to-South development interventions and not prioritising what the white gaze wants but supporting local communities’ needs and requirements. Co-design is perhaps one way to do this.

Many education development projects involve the production and sharing of resources designed to support education professionals and/or learners in implementing policy aspirations. The intention is that through support in new pedagogies, the quality of teaching and the quality of learning will improve. A priority is that these resources are co-designed in context, so that not only do they ‘speak’ to users and partners, but the process builds capacity and shared understandings of ideas which underpin the policy aspirations and issues that are being tackled, together with offering an authentic local interpretation.

Co-design is a term used more commonly in the field of product, software or urban design, and architecture than education. Nevertheless, some of the principles identified by those working in these fields apply to the development of educational resources. Co-design has been described as a process of ‘joint enquiry and imagination’ in which ‘problem and solution co-evolve’. It is about user empowerment and democratisation, and sustainability.

It is generally accepted that ‘co-design’ of educational resources (courses and materials) is a ‘good thing’. Why is this? Perhaps it is because it is more democratic and more equitable. Co-design ensures that the resources are contextually relevant and reflect the views of multiple stakeholders. It increases the likelihood that the resources will be used and can build capacity through social learning and participation. There is also an assumption that it leads to higher quality resources. However, it remains one of those concepts which is accepted uncritically. It would be difficult to argue against the notion of co-design, yet there is very little guidance about how it might be achieved, or evidence that it has been successful.

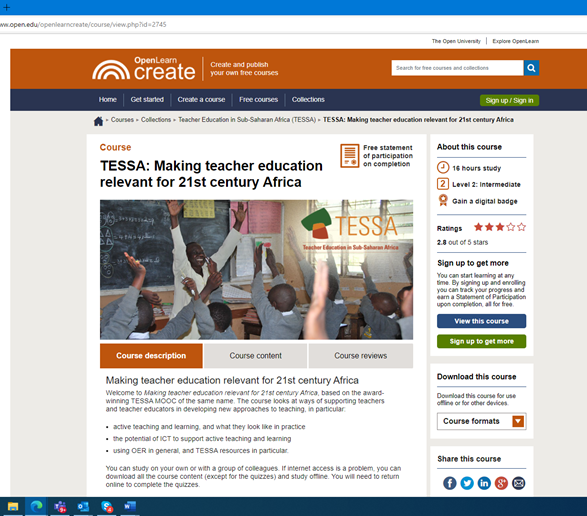

At the Open University, most of our International Development work involves the co-design of educational resources and free online courses to support professional development (e.g. www.tessafrica.net; OLCreate: Active teaching and learning for Africa: ZEST (open.edu); OLCreate: Professional Development for Inclusive Education (open.edu). We work within a quality assurance framework which aims to protect our reputation but by its very nature this sometimes limits the opportunities for genuine co-design: ultimate ‘sign-off’ lies with our institution, a somewhat hegemonic approach to co-design.

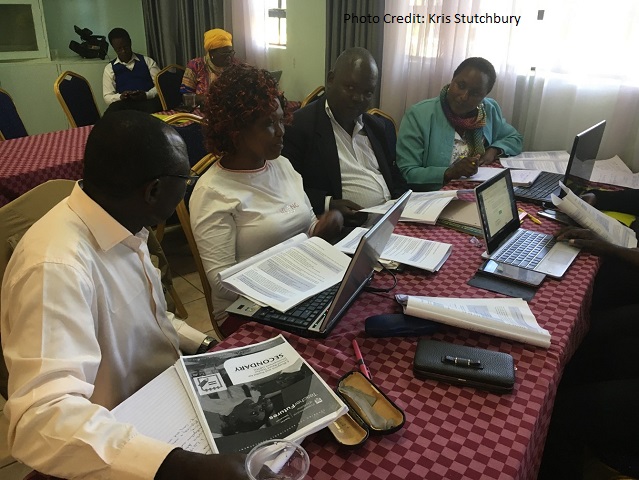

Nevertheless, over the course of several significant projects we have tried and tested co-design processes which involve workshops (both in person and online), versioning, critical review in context and the conversion of tried and tested workshop activities and outputs into online activities that are part of a course. Perhaps ironically, the least successful form of co-design has been the delegation of authoring to different partners, despite the fact that to an outsider this is perhaps what co-design should mean. It is often difficult to gather the text within the time schedule required and the Open University processes mean that after critical review and editing, individual contributions are often not recognisable. This can be very de-motivating and disempowering for local authors, and it is difficult to explain that without their contribution the resources could not have developed as they did.

Despite considerable success with resources that we have developed, (e.g. the PIEoneer Digital Innovation of the Year Award in 2018), there is some uneasiness about the extent to which the resources really are ‘co-designed’. There is much still to learn and understand.

- What do we mean by ‘effective co-design’ in the context of developing resources to support teacher education in Africa?

- What are the possible models for co-design in the context of international educational development and how do they work?

- How can co-design challenge colonial and hegemonic structures of power?

- Does co-design represent value for money – cost (extra time/expense) vs benefit (capacity has been built)?

- What needs to be in place to support co-design processes?

- What are the opportunities and challenges presented by ‘co-design’?

- Does co-design ‘build capacity’? Which aspects of the process contribute to capacity building.

- And finally ……what evidence do we need to assess whether the processes have been successful.

This is fertile ground for further research. Like most aspects of education, good co-design is probably about relationships, but building those equitably across cultural, economic and geographical boundaries remains an ongoing challenge.

The notion of co-design is by no means original or new. This concept is very present in the field of the scientific research and no one could deny that international prizes have very frequently been granted to different personalities working together. In the pedagogical arena scores of contributions have been produced and published. So my contention is that it is a good idea to work in groups to figure out challenges and navigate solutions. We need to trust human ability to work together for common solutions. It could be a trust building approach and so co-design could lead to confidence building and it could contribute to decolonize mentalities and curve the so-called ‘white gaze’ .