This blog was written by Dr Israel Moreno Salto from the Autonomous University of Baja California, Mexico and Professor Ricardo Sabates from the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. This blog was originally published on the PAL Network website on 24 May 2021.

Earlier this year, the World Bank released the publication Primer on Large-Scale Assessments of Educational Achievement. This book comes as a response to emerging questions around how best to address the complexities of the processes for designing, administering, analysing and using data generated from large-scale assessments (LSAs). Although this publication is not the first of its kind (see OECD, 2013; Tobin et al., 2015), it is distinctive in its thematic scope.

We commend the World Bank’s willingness to pursue and expand these discussions, from which there is still much to be learned. In the spirit of these conversations, and grounded in a recent study of LSAs in Mexico, we put forward four broad issues that require further consideration.

1) The socio-cultural context in which LSAs are developed is not neutral

The argument put forward by the World Bank is that LSAs need to be designed by expert psychometricians in consultation with experienced educationalists and relevant actors. Yet, experts have to make decisions about which knowledge is to be captured in the LSA and from whom. The way in which knowledge is captured is likely to emulate or reproduce inequalities that already exist in any education system. As such, LSAs alone cannot respond to the question of why inequalities exist, but can only indicate that these inequalities, as measured by this particular tool and for a group of representative students, exist.

Mexico, like many other countries, takes part in different LSA programmes. At the global level, Mexico participates in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), a survey designed to gauge the extent to which 15-year-olds enrolled in secondary or upper secondary schools have acquired a certain level of generic mathematics, literacy and science skills. Regionally, Mexico is also part of the Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (ERCE, after its acronym in Spanish), focusing on gauging common core competencies between Latin American countries of students enrolled in Grades 3 and 6 of primary school. Nationally, Mexico has also developed its own LSA, namely the National Plan for Learning Assessment (PLANEA, after its acronym in Spanish), which measures the extent to which students have achieved national curriculum competences in key grades of all compulsory schooling stages.

Each of these LSAs has its own designers, who seek to capture different information, skills or competencies. Each of these LSAs target different groups of children from across different levels of education. Unfortunately, the design of these diverse LSAs is seldomly accompanied by information about the designers themselves, their own biases, reflections about why the selected knowledge in the LSA matters and for whom this knowledge matters.

2) LSAs require a more nuanced understanding of different audiences

After designing the LSA, and after selecting participating schools and pupils, and assuming the correct administration and analyses, the World Bank publication recommends targeting and tailoring the dissemination of results. While we agree this is important, many LSAs fail to acknowledge the complex arrangements, dynamics and needs of the diverse audiences they intend to serve. For instance, policymakers are a target group for LSA data. In Mexico, policymaking can be achieved by decree from the Ministry of Education or by legislation from Congress. To this end, considering that policymaking within these two groups follows different routes and is subject to different habitus, it would be naive to think that the same data set would be equally useful for both groups. Even within the Ministry of Education, there are diverse needs. Our research shows that whilst high-ranked officials cited the use of Mexico’s position in league tables using PISA, lower-ranked officials stated that they required more technical data from LSAs in order to support the development of a new national curriculum.

We argue that producers of LSAs require a more nuanced understanding of the nature and needs of the different audiences they intend to serve and the extent to which evidence emerging from LSAs may or may not be fit for purpose.

3) Expanding communication mechanisms of LSA data

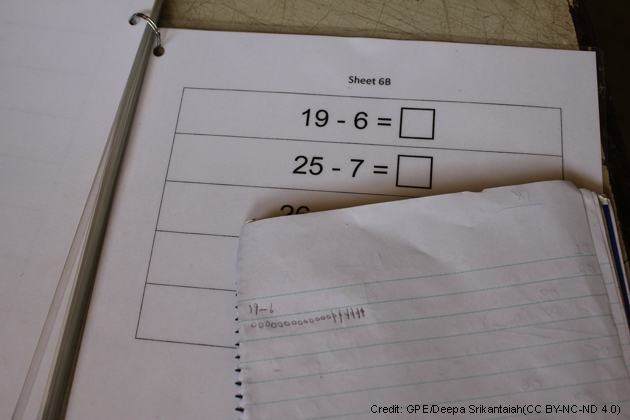

There is no question that LSAs are proficient in generating data. However, communicating this data effectively to those it intends to serve remains a significant challenge. Our research shows astonishing differences about LSA data knowledge and consultation among teachers. Based on a survey conducted in 5 cities and 30 schools in Mexico, we found that 1.6% of teachers know ERCE, and less than 8% of teachers have read publications developed by the National Institute for Education Evaluation aimed at helping teachers improve their practices.

While many LSA developers do provide reports accessible online, not all teachers in remote areas have access to technology. Furthermore, key publications remain in official or national languages, making it difficult for ethnic minorities to make sense of these results (particularly when LSAs contain a boost sample for ethnic minorities within specific contexts). Taking a clue from Nancy Fraser’s work on social justice[i], while representation matters, this is not enough, LSAs also require further work on issues of recognition, participation and redistribution.

4) Learning from past failures and successes

There is a tendency when sharing information to only draw on the successes. This form of drawing lessons from best practices is common amongst LSAs; it is at the heart of what Pawson and Tilley[ii] would refer to as their “programme ontology”, that is, their internal theory of how programmes work. However, what is less common is the acknowledgement that in many cases LSAs have led to unintended consequences. In this regard, Nichols and Berliner[iii] provide a detailed account of the multiple ways in which LSAs have been misused in the USA. In Mexico, for instance, rather than using reflective and active pedagogies, certain schools were regularly testing children using previous national assessments and tracking students’ progress through these metrics.

Notably, there are few warnings about these kinds of issues in any publications emerging from LSAs. It is therefore important that LSAs provide acknowledgements of the potential limitations for users to draw upon.

Overall, the World Bank has taken an important step in the right direction with this publication. In this blog, we aim to provide observations so that we can continue to build up knowledge in the field of LSAs for educational improvement. To this end, we hope that our observations are seen as a way of instigating further conversations and bringing alternative voices to the discussion.

About the authors

Israel Moreno Salto has a PhD in Education from the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge. He is currently a Lecturer of Educational Sciences at the Autonomous University of Baja California. Prior to this, he worked for over 10 years as a schoolteacher in different education levels in Mexico, such as pre-school, primary, secondary and teacher education.

Ricardo Sabates is Professor of Education and International Development at the Faculty of Education of the University of Cambridge.

[i] Fraser, N. (2019). Nancy Fraser, social justice and education. Routledge.

[ii] Pawson, R. and Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. Sage.

[iii] Nichols, S. L. and Berliner, D. C. (2007). Collateral damage: How high-stakes testing corrupts America’s schools. Harvard Education Press.

Very useful review. Thank you. Learning from past ‘failures’ is as important as learning from past ‘successes’. All too often null and negative results are excluded from reports.

Dear Professor Little, thank you for taking the time to comment, much appreciated. We hope that our comments can mobilise reflections and conversations around the benefits of acknowledging, amplifying and learning from past LSA mistakes and shortcomings. During the research that I undertook in Mexico, I found that middle level education authorities and school leaders who strive to make use of LSA data tend to be unaware of past mistakes and unintended consequences. We are convinced that addressing these issues may help reduce, mitigate or even perhaps prevent them from occurring in other settings. Also, large-scale assessment programmes can benefit from this by addressing one of the strongest points of criticisms that they endure.