This blog was written by Jessica Oddy, Accelerated Education Working Group (AEWG).

Accelerated Education (AE) is a crucial intervention for over-age, out-of-school children and youth aged between 10-18 years of age. The Accelerated Education Working Group (AEWG) defines AE programmes as: “flexible, age-appropriate programmes, run in an accelerated time frame, aiming to provide access to education for disadvantaged, over-age, out-of-school children and youth – particularly those who missed out on or had their education interrupted due to poverty, marginalisation, conflict, and crisis.” The SDGs clearly articulate the need to reach out to all children and youth with appropriate educational opportunities. The AEWG believes that AE is an integral approach to meet this need. The AEWG is made up of education partners working in accelerated education. UNHCR currently leads the AEWG with representation from UNICEF, UNESCO, USAID, NRC, Plan, IRC, Save the Children, Education Development Centre, ECHO, and War Child Holland.

Accelerated Education (AE) is a crucial intervention for over-age, out-of-school children and youth aged between 10-18 years of age. The Accelerated Education Working Group (AEWG) defines AE programmes as: “flexible, age-appropriate programmes, run in an accelerated time frame, aiming to provide access to education for disadvantaged, over-age, out-of-school children and youth – particularly those who missed out on or had their education interrupted due to poverty, marginalisation, conflict, and crisis.” The SDGs clearly articulate the need to reach out to all children and youth with appropriate educational opportunities. The AEWG believes that AE is an integral approach to meet this need. The AEWG is made up of education partners working in accelerated education. UNHCR currently leads the AEWG with representation from UNICEF, UNESCO, USAID, NRC, Plan, IRC, Save the Children, Education Development Centre, ECHO, and War Child Holland.

Globally, accelerated education programmes (AEPs) are employed frequently to address many out-of-school children and youth. However, in practice, there is an incredible diversity of programs labelled AEPs. In addition, research, AE reviews and mapping conducted by the AEWG has highlighted a high degree of variability in the intensity and quality of implementation of various accelerated learning and education components.

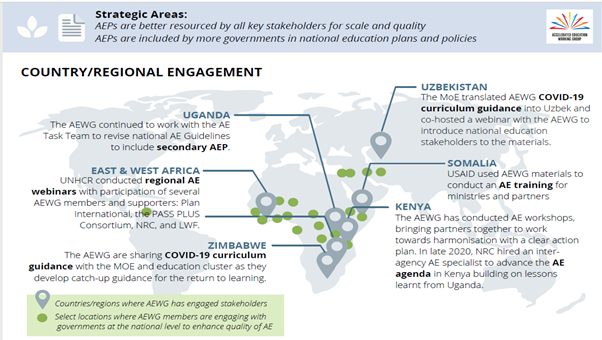

The AEWG’s goal is to strengthen the quality of accelerated education programming by working at a global level, developing tools and guidance to improve programme quality and at a national level working with Ministries of Education and key stakeholders in-country to create a more harmonised approach to AE through supporting with developing national guidelines, policy and curriculums.

The September 2021 UKFIET conference was an opportunity for the AEWG to organise a symposium, bringing together Ministry of Education (MoE) representatives, Accelerated Education practitioners and researchers. It evidenced the process of anchoring AE programmes into national frameworks in Kenya, Uganda, and Somalia. To date, there is little evidence on how AE has been integrated into national systems, the processes of harmonisation, and how evidence and lessons learned from other contexts can shape and inform national policy and frameworks. This symposium sought to address this evidence gap.

In each country case study, widespread variation exists in how AEPs are planned, implemented, and approached, with little or no overarching objectives, guidance, standards, or indicators for effective accelerated education (AE) provision.

Lessons from Uganda

In 2018, a series of national-level workshops, supported by the AEWG, were held to develop national AE Guidelines based around the AEWG 10 Principles for Effective Practice. An AE task team, made up of multiple actors and MoE representatives, was also formed in 2019 to drive the harmonisation agenda. Ms Joyce Adoch Talamoi ( Norwegian Refugee Council, based in Uganda) and Sarah Ayseiga (Ministry of Education and Sports, Uganda), representatives of the AE task team, explained the success of the AE task team, which includes to date :

- Contextualised AEP guidelines for Uganda. The approval process is in the second last stage of approval by the Ministry of Education and Sports

- An AE Curriculum developed in collaboration with the National Curriculum Development Centre (Primary & Lower Secondary)

- Secondary AE initiated and currently being piloted

- Supporting transitional pathways – beginning with a mapping tool

- Strengthening the referral process for child protection and other needs

- Supporting appropriate placement (AE placement tool flowchart)

- Development of Primary AE specific textbooks.

Lessons from Kenya

The AE harmonisation process was initiated in Kenya in 2020 in response to an increased demand for AE interventions and the recognition that partners were responding in an uncoordinated manner without the official MoE endorsement. David Kivoto, deployed to support the harmonisation process in Kenya, discussed how harmonisation of AE is critically needed and the evidence that they are drawing on from the Ugandan process. In recent months, the MoE approved the AE harmonisation process and will lead it by appointing a technical working group.

Lessons from Somalia

In Somalia, Mohamed Hassan Mukhtar, Director of Curriculum in the Ministry of Education, Culture and Higher Education (MoECHE), and Abdulaziz Nur Mohamed, Director of TVET & Non-Formal Education, shared how, over the past year, the MoE has been working with a variety of education stakeholders to mainstream and harmonise AE. Following an in-depth analysis of national policies and the formal curriculum, an Accelerated Basic Education (ABE) Policy and ABE Curriculum Framework were drafted and revised by the MoECHE and then sent out for consultation at state level with all stakeholders before final decision validation by the Minister. These two documents and the formation of the ABE Task Force have proved instrumental in harmonising the AE programmes and their alignment with the formal education system.

The ABE in Somalia has also been piloting the AEWG Introductory Teacher Training Pack and trained 30 trainers and 746 ABE teachers. Sue Nicholson (Bar amo Baro) highlighted that evidence-based pedagogies informed the AEWG AE teacher training package. Whilst there have been several challenges, Somalia has made tremendous strides in setting up an AE system. They credit their success to the strong relationships between the partner, donor and ministry of education.

Lessons learned

The AEWG, through its learning agenda, aims to organise and generate evidence to inform strategic planning, project design, project implementation, monitoring and evaluation and in-service training efforts of AE. All of the four case studies offer examples of practices for the global community.

While each country is at different stages of harmonisation, the real-time evaluative and evidence gathering offers fresh insight and learnings for practitioners and academics interested in the global provision of equitable access to quality basic education, particularly for fragile, insecure, and underfinanced environments. Across all contexts, the panellists highlighted the importance of relationships, collaboration combined with dedicated expertise to drive forward sustainable and harmonised AE.