This blog was written by Emma Wagner, Senior Education Policy and Advocacy Adviser at Save the Children. It was originally published on the INEE website on 12 January 2021.

The Progress Under Threat report referenced in this blog can be accessed here.

The COVID-19 pandemic, rather than being the ’great equaliser’, has shone a light on and increased inequalities.

The most marginalised children including refugees have been worst hit. A recent study by the World Health Organisation reveals that the pandemic has had a disproportionately harmful impact on refugees around the world.

COVID-19 has compounded existing education inequalities that prevent refugee children from fulfilling their right to quality education and building a better future for themselves and their communities.

Refugees’ access to education before the pandemic

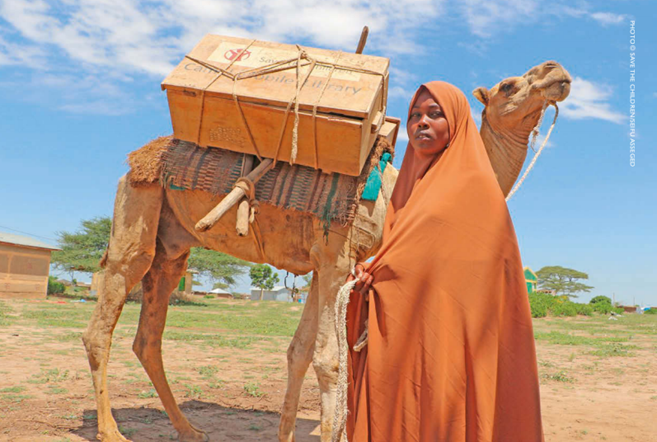

Like 26 million other children in Ethiopia, Mahadiya, 13, is out of school because of COVID-19, but thanks to Save the Children’s camel library, she is able to continue reading and learning at home.

Almost half of all school-aged refugees – 3.7 million – were out of school even before the pandemic. Access to education for refugees varies significantly from country to country, within countries and at different education levels. In Ethiopia, only 67% of Sudanese refugees are in primary school and 13% at secondary. Refugee girls – particularly adolescents – are almost three times more likely to be out of school than their non-refugee peers.

Even once in school, refugees, alongside their host community peers, are not learning due to the low-quality of education available. This puts their development, learning and wellbeing at risk, and causes high drop-out rates. Displaced children may have experienced severe trauma and require psychosocial support in schools or referral to specialised services.

Whilst early childhood care and development in emergencies, alongside parent and caregiver education, is increasingly recognised as providing lifesaving support, analysis from the Moving Minds Alliance analysis shows that it received just 3.3% of all development aid in 2017.

The majority of countries hosting large numbers of refugees have weak education systems that already struggle to meet the needs of the most marginalised host populations. These countries need international support to scale up education services and provide alternative educational opportunities for refugees.

However, progress was in sight

The 2018 Global Compact on Refugees includes the landmark global commitment to provide ‘more direct financial support and special efforts will be mobilised to minimise the time refugee boys and girls spend out of education, ideally a maximum of three months after arrival’.

This time last year, education ‘stole the show’ at the first ever Global Refugee Forum, where hundreds of policy and financial pledges were made in support of the global commitment to get refugee children in school and learning.

228 pledges included references to education with over half solely on education (based on analysis of data accessed November 26th 2020). Of these education pledges around half focussed on delivering compulsory education (early childhood through secondary), with the remaining targeting Technical and Vocational Education and Training and higher education.

One third of the pledges were for material and/or technical support, 28% were legal or policy pledges, and 20% were financial pledges. Just under a third were from states – either refugee-hosting countries or donors – and a similar proportion from NGOs. 10% came from the private sector with the rest from academics and researchers, local government, and faith-based organisations.

Implementing these pledges in full could catalyse much needed progress for refugee education.

One year on, what progress has been made on these pledges?

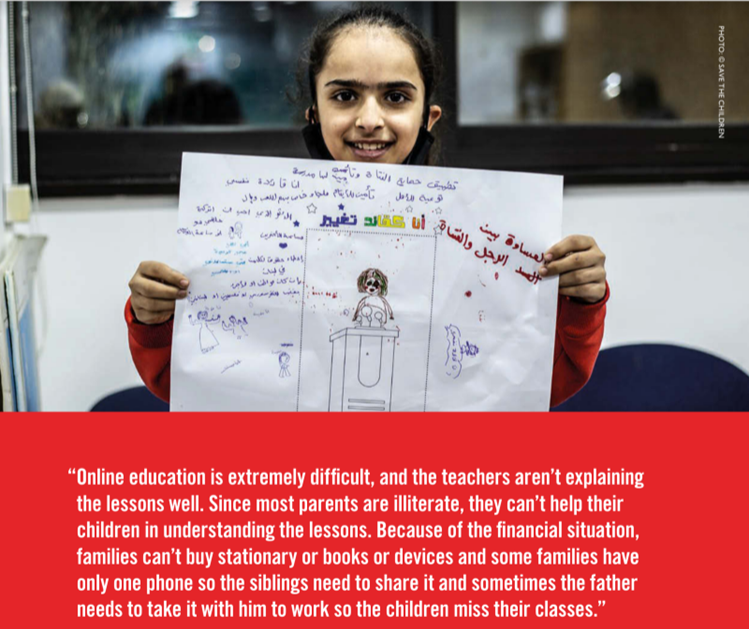

Ghinwa, 12, Syrian refugee girl living in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. She holds up her artwork showing what change she would make after role-playing a decision-maker in an activism workshop.

Save the Children’s new report Progress under threat: Refugee education one year on from the Global Refugee Forum and the impact of COVID-19 shows that just 9% of pledges have been fulfilled with available data. 71% are in progress with 20% still in the planning stage.

However one year on, status updates have not been shared for more than half of pledges. While we recognise that implementation of many pledges has almost certainly been impacted by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, we urge strongly encourage all pledge‑makers to report against their pledges at least once per year.

Our analysis of the ten largest refugee hosting countries where Save the Children works, shows that progress to deliver on the pledges has indeed been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Where refugee children were in school, their learning has been disrupted by school closures and challenges accessing distance learning, increasing their vulnerability. Evidence demonstrates this has led to increased rates of child labour, gender-based violence, sexual exploitation, child marriage, and child pregnancy among refugee communities.

In Uganda, despite some schools having re-opened, more than 13 million children remain out of school since the end of March last year, including 600,000 refugee children. In Nwoya district in northern Uganda, figures show that cases of both teenage pregnancies and child marriage doubled, and rates of child labour tripled between April and June last year, while children were out of school. Due to difficulties in reporting these issues, the real picture is likely to be far more serious.

However new initiatives are helping to meet refugee children’s learning and wellbeing needs. The outcome paper from a high-level roundtable on refugee education and COVID-19 highlights key emerging experiences, learnings and promising practices.

Action is needed now to get back on track

A young Rohingya refugee learning Burmese language in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. With the camp’s learning centres temporarily closed because of COVID-19, some home-based learning is being provided. Photo: UNHCR/Iffath Yeasmine

Our report sets out recommendations for the Global Refugee Forum process, refugee hosting countries, and donors including the World Bank to ensure we do not lose sight of the promises made to refugee children.

We strongly encourage all pledges be ambitious, specific and include timelines for completion to allow accountability mechanisms to properly track progress.

Our analysis highlights the importance of including refugees in national education systems and in the COVID-19 education response. Governments should provide refugees the additional support they require to access distance learning and return to school safely, such as learning materials, EdTech initiatives, cash transfers, back to school campaigns, mental health and psycho-social support and language support. More details and costings for these interventions can be found in Save Our Education Now.

The international financing response to the COVID-19 education emergency has been dismal. Just 5.7% of the US$342 million required for education under the COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan has been funded. Donors should meet the funding needs for refugee education as part of the responsibility sharing principles of the Global Compact on Refugees. This can be done through increasing bilateral funding for education, and fully funding the Global Partnership for Education and Education Cannot Wait.

If we exclude refugees from the COVID-19 response, we will all bear the costs.

The views expressed in this blog are the author’s own.