This blog was written by Inderjit Bains, PhD student, University of Birmingham. Inderjit’s research explores the role of the private sector in shaping learning experiences and outcomes for disadvantaged children in India.

In India, the movement towards the inclusion of all children into the education system has been steadily gaining momentum, and the private sector has been increasingly viewed as possibly solving long-standing social divisions within the system. In particular, Section 12(1)(c) of the recent Right to Education Act (RTE) has been heralded as potentially providing greater opportunities for disadvantaged children to gain a quality and inclusive schooling experience. Yet little is still known about the experiences of children who have gained private school placements through the Section 12(1)(c) provision. How easily can children disadvantaged by, for example, socio-economic status, caste, gender or disability access a placement? What kind of learning and wellbeing experiences do these children encounter in schools under the provision? And how have experiences been affected by the current Covid-19 crisis?

To address these questions, my recent MA Social Research dissertation explored the inclusion experiences of disadvantaged children seeking or learning through Section 12(1)(c) placements and how their inclusion has been further impacted by the Covid-19 crisis. By utilising Save the Children’s (2017) ‘Quality Learning Framework’, I conducted nine in-depth qualitative online interviews with academics, policymakers, NGO workers and teachers in India to evaluate access, learning and wellbeing experiences such children encountered before and during the pandemic.

Access, learning and wellbeing through RTE Section 12(1)(c)

Where accessing private schools is concerned, interviews highlighted how parents of disadvantaged children experience difficulties when applying for Section 12(1)(c) places with respect to obtaining requisite documentation. For example, one interviewee working in policy and academia explained “it requires proof of income, proof of residence, proof of caste” which is “very tricky”. One NGO worker interviewed also described how the application process can be made particularly onerous for many parents who “probably don’t know how to read and write English” and “probably don’t have internet connections”.

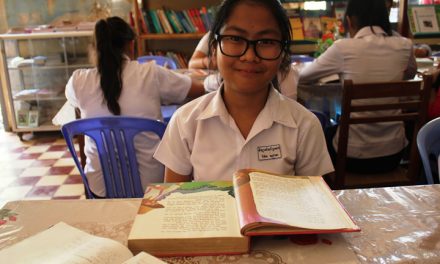

In terms of learning, once placements have been taken up difficulties often arise due to educational and social gaps between disadvantaged learners and their more advantaged peers. One teacher highlighted how “there are huge learning gaps and if you put them in a main classroom they’re lost.” Learning difficulties were attributed directly to the impact the RTE provision has had on the composition of classrooms where several interviewees argued it has created divided learning spaces.

Interviews also revealed how children’s home situations in both rural and urban contexts can greatly affect school wellbeing experiences because children may have extra domestic responsibilities which affect their learning engagement. Furthermore, the idea that home situations cause personal and psychosocial problems at school was also reflected. One policy worker described how “the school environment is completely foreign to them, then they go back to an environment which is…dramatically different”, and argued these home conditions are “the bedrock of inequality”.

The impact of Covid-19

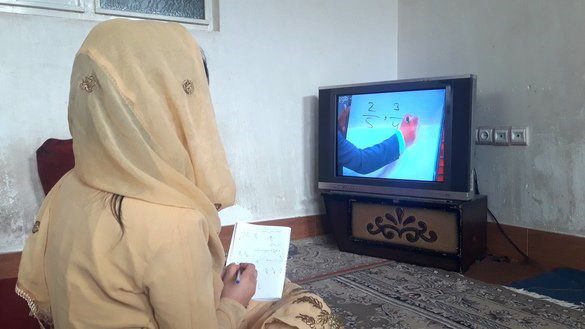

My study highlighted how Covid-19 is further exacerbating inclusion problems for disadvantaged children. Accessing online learning has been difficult due to the lack of mobile devices and access to Wi-Fi or mobile data, and the children of labourers and migrants have been particularly affected by this issue. Moreover, there is the potential for children dropping out because of school closures, which appears to be affecting girls particularly. One NGO worker explained that “many girls dropped out during the lockdown… it also led to an increased number of child marriages.”

The lack of support from schools and parents during the pandemic is also resulting in significant learning losses. Another NGO worker described the situations as having “horrible” consequences where many children “will return to school post-Covid… and they will be put in the next class without knowing anything.” Meanwhile, teachers have faced difficulties supporting disadvantaged children with close one-to-one attention where workloads have significantly increased.

In terms of wellbeing, the Covid-19 situation is threatening children’s physical and mental health as families are falling into poverty and home situations are becoming more stressful. One policy worker argued, the pandemic has created “a situation of widespread trauma” because “the setback is at the house where… somebody’s lost their job, or people have not earned money.” Interviews also highlighted how the loss of a safe, more spacious and comfortable learning environment at school is also leading to greater discomfort for disadvantaged children at home.

Future research and policy recommendations

Access: It would be particularly interesting to learn more about whether recruitment for the Section 12(1)(c) provision has continued during the pandemic, given little is currently known about this situation. Policy changes should include campaigns to generate increased awareness of the provision, and greater administrative support is needed for parents with administrative issues when applying.

Learning: The study revealed that inclusive learning largely depends on teachers’ attitudes and approaches, and further research could include in-depth qualitative research into this issue. Greater attention on training is required to ensure teachers understand the need to take a supportive and inclusive approach, with particular support for girls who are more likely to drop out.

Wellbeing: Future research could explore the impact of home situations on learning for disadvantaged children, and interviews and ethnographic research with parents and children would be valuable here. Policy changes could include greater financial and counselling support whereby schools work with local government, NGOs and community groups to identify and support those who are most vulnerable.