This article was written by Louise Yorke, Research Associate, and Pauline Rose, Professor, REAL Centre, Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, UK; Tassew Woldehanna, Professor, Department of Economics, and Belay Hagos Hailu, Associate Professor, Institute of Education Research, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. It was originally published on the NORRAG website on 25 October 2021.

This NORRAG Highlights is cross-posted by Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) and NORRAG. This article was part of NORRAG Special Issue 06 titled “States of Emergency: Education in the Time of COVID-19”, which was released on 6 October 2021. This article draws on evidence from research carried out with government officials, school principals, teachers and donors in Ethiopia, and explores the education system response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Ethiopia. Additionally, the authors examine the bottlenecks in the education system, as well as the inequalities which limit the potential for effective response, and reflect on the best path forward.

The unequalising impacts of the COVID-19 school closures in Ethiopia

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring inclusive and equitable quality learning, as set out in Sustainable Development Goal 4, has become even more challenging due to the unequalising effects of the crisis (Stewart, this issue). In Ethiopia, the significant gains made in education in recent decades are now threatened. This is likely to have lasting consequences for students’ development and outcomes. An important challenge is the growing inequalities between different groups of students, especially across gender, location (region, rural-urban) and income-level. These inequalities are likely to be compounded by the adverse socio-economic impacts of the pandemic on individuals, households and communities. As a result of school closures, which began in Ethiopia in March 2020, approximately 26 million primary school students were out of school for at least six months. To support students’ distance learning, the government put in place a number of measures including lessons broadcast through radio for primary school students. They placed special emphasis on supporting disadvantaged students stating, “…vulnerable and disadvantaged children are the most affected and hence will be given special emphasis during this complicated crisis” (MoE, 2020, p. 1). Yet, studies suggest distance learning did not reach all students, and those already facing the greatest disadvantages received the least support (Azevedo et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Wieser et al., 2020).

Thus, strengthening the education system for equitable learning is imperative and much focus has turned to “building back better” and more efficient education systems, resilient to future shocks. Ethiopia presents a case study for considering what is needed to revitalise progress made prior to the pandemic, given that strengthening the education system for equitable learning has been a consistent priority of the government, one that has become even more urgent in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

RISE Ethiopia distance research

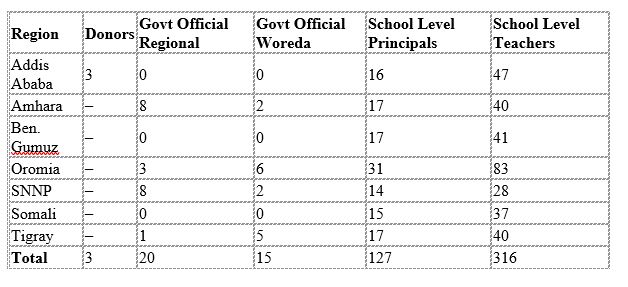

The Research for Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Ethiopia research study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic included phone and online interviews with donors, government officials (regional and woreda [district]), school principals and teachers across seven locations (regions and city administration) (Table 1). The inclusion of different stakeholders provided the opportunity for a system-level perspective of what took place in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we were limited in our ability to include stakeholders who lacked access to technology.

COVID-19 education system response strategy. We focus on how the needs of different groups of students were included at the planning stage, the system-level factors that influence the support that they received and the likely impact on their education and development. Based on these insights, we reflect on what is needed for strengthening the education system for equitable learning.

Information and support for responding to the COVID-19 pandemic

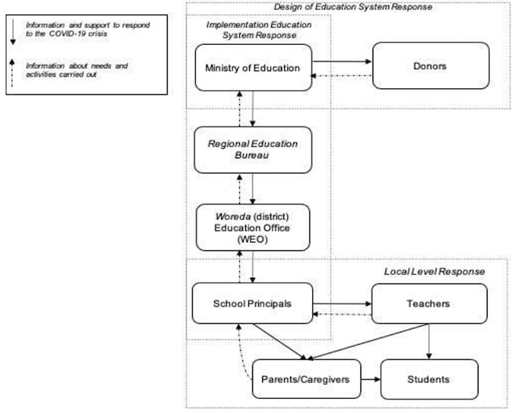

Given the changing nature of roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in the education system in the context of COVID-19, receiving adequate information and support to rapidly respond to the pandemic was imperative. However, we found that stakeholders – especially those at school-level – did not receive sufficient information and support to enable them to respond effectively. This was primarily due to an over-reliance on a cascade flow of information and support from the Ministry of Education to the Regional Education Bureau, the Woreda Education Office and then to school principals and teachers (Figure 1). Information was lost from one level to the next, meaning that school-level stakeholders were least likely to receive the information and support that they needed. School principals and teachers living in rural and remote regions and female teachers were least likely to receive support, due in part to more limited access to phones in these locations. Eighty-nine percent of rural school principals had access to a phone compared with 100% of urban school principals. Meeting face-to-face was more of a challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for female teachers, more likely to have an increased domestic workload.

Inefficient flows of information meant that collaboration and coordination across different levels of the system were limited. There were good levels of communication between stakeholders at different levels of the system, i.e., between donors and MoE officials and between regional and woreda level officials, but communication across these different levels remained limited. Stakeholders held different views about the challenges that they believed the pandemic presented and what was needed to respond.

Supporting school principals and teachers to respond to school closures

Inefficient flows of information and support had knock-on consequences for school-level stakeholders’ response to school closures and impacted their ability to support students’ distance learning. School principals and teachers who received information and support were significantly more likely to report supporting distance learning during the school closures, controlling for differences across gender and rural-urban location (Yorke et al., 2021). As reported in other contexts (e.g., Stewart, this issue), less than half of teachers in the sample were engaged in providing distance support for students’ learning, with rural teachers less likely to indicate that they were providing support. Other challenges reported by teachers included limited access to technical equipment (such as computers) and lack of confidence in their ability to deliver and support distance learning.

How effective was distance learning?

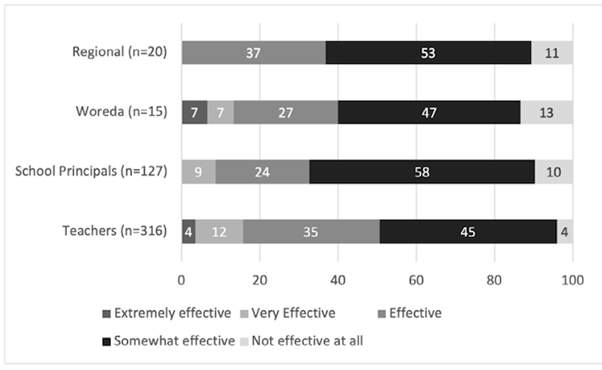

Stakeholders at all levels of the system (regional, woreda and school-level) were more likely to view the government’s education system pandemic response strategy as only “somewhat effective” in supporting students’ distance learning, including the overall response strategy and the educational programmes broadcast through radio (Figure 2). Students from low-income families and rural students were perceived as least likely to benefit from the support provided, as they did not have access to the required technology and would be more likely to be engaged in work activities. Teachers included in the sample suggested the majority of parents and caregivers would be unable to support students’ learning due to the high work demand that parents were facing, together with their low literacy levels. As captured by Stewart (this issue), inequalities in parents’ own educational level is likely to produce further inequalities.

Figure 2. Perceived effectiveness of educational programmes broadcast through radio reported at different levels of the education system (%)

Participants highlighted how disadvantaged students were likely to face further challenges due to the range of additional in-school supports that they would miss out on, such as school-feeding for students from low-income families, emotional support for girls and children with disabilities and peer-to-peer support for low- performing students and rural students (Figure 2). These findings are consistent with other related RISE Ethiopia research that has also highlighted the inadequate support that disadvantaged students received during the school closures, especially children with disabilities. Although the government outlined the importance of responding to the needs of disadvantaged students at the planning stage, the strategies put in place did not cater for the needs of different groups of students, especially those who are most marginalised, or take account of the varied roles that schools play in students’ learning and development.

Challenges for reopening schools

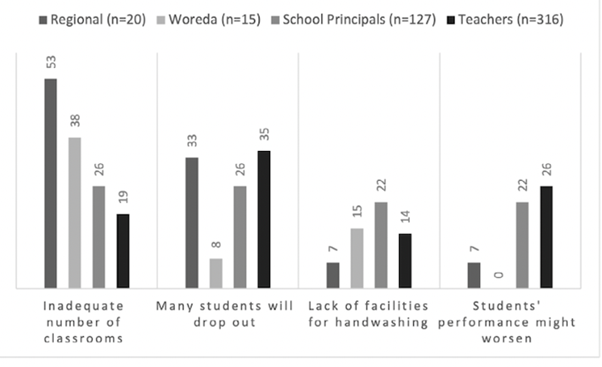

Anticipated challenges for schools reopening, including inadequate number of classrooms to implement social distancing, inadequate hand washing facilities and reduced number of teachers (Figure 3), highlight the need for bringing more resources into the education system.

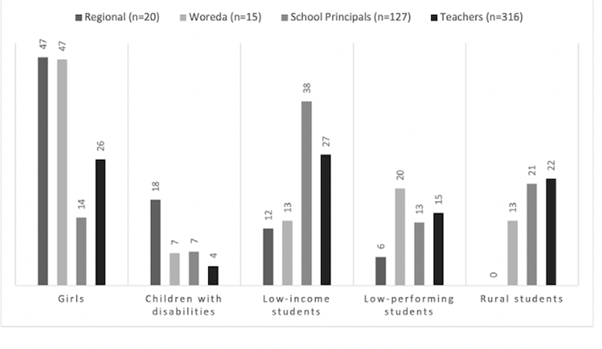

Increased student dropout was the challenge most reported by school principals and teachers. Girls and low-income students were believed to face the greatest challenges in returning to school (Figure 4).

Despite these concerns, only two-thirds of school principals reported that they were making plans to support disadvantaged students to return to school, although school principals who had contact with parents and caregivers during the school closures were likely to report making these preparations – suggesting they were more attuned with the needs of disadvantaged groups.

For all stakeholders, catching up on lost learning was imperative, with some suggesting that the government’s current approach was insufficient and did not account for students’ varying needs. Many donors, and regional and woreda-level government stakeholders believed the government’s policy of automatic promotion was necessary during COVID-19. But school-level stakeholders believed this would lead to the further deterioration of education quality and negatively impact students’ learning, especially low-performing students who may struggle to catch up. They considered efforts to catch up on lost learning should seek to identify individual student needs, especially for students from low-income families, girls and rural students, and adapt responses accordingly. Others identified a need to equip students with skills for independent study and to encourage parents to support children’s learning.

Strengthening the education system for equitable learning

These findings highlight that despite the swift response of the government to the Covid-19 school closures, disadvantaged students are least likely to have received support during this time. This was due to bottlenecks within the education system, including the unavailability of up-to-date data and evidence, limited involvement of local-level stakeholders and over-reliance on the cascade flow of information within the system. Existing inequalities across location (region and rural-urban), income-level and gender mean that support was least likely to reach those who needed it the most.

This analysis provides lessons for efforts to strengthen the education system in Ethiopia and related contexts to address growing inequalities within and between groups of students. Better data and evidence to identify and respond to the evolving and “hidden” needs of different groups of students is required. Greater efforts to include local level stakeholders in the design of strategies could help ensure they are more closely aligned with local needs. There is a need to move beyond focusing on academic learning alone to consider students’ holistic needs, including physical needs, socio- emotional learning, mental health and wellbeing. Improved information flow and communication within the system would help to ensure that all stakeholders are informed and supported to respond to challenges as they arise, ensuring better collaboration and coordination.

References

Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Iqbal, S. A., & Geven, K. (2020). Simulating the potential impacts of COVID -19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes: A set of global estimates. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9284.

Kim, J., Araya, M., Ejigu, C., Hagos, B., Rose, P., & Woldehanna, T. (2020). The implications of COVID -19 on early learning continuity in Ethiopia: Perspectives of parents and caregivers. Research and Policy Paper No. 20/11. REAL Centre, University of Cambridge.

Ministry of Education (MoE) (2020). Concept note for education sector COVID-19 preparedness and response plan. Ministry of Education.

Wieser, C., Ambel, A. A., Bundervoet, T., & Tsegay, A. H. (2020). Results from a High-Frequency Phone Survey of Households (No. 148890, pp. 1-9). The World Bank. Washington, D.C.

Yorke, L., Rose, P., Woldehanna, T., & Hagos, B. (2021). Primary school-level responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Ethiopia: Evidence from phone surveys of school principals and teachers. Perspectives in Education.