This blog was written by Guglielmo Fasana, Intern, UNESCO’s International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP-UNESCO), with inputs from Barbara Tournier, Programme Specialist, IIEP-UNESCO, and Charlotte Jones, Global Head of Research and Development, Education Development Trust.

If prompted to think about the education workforce, most people would likely visualise teachers and principals. Others would point towards officials from education ministries. While these are undoubtedly two sets of key players in designing and implementing educational policies, they are by no means the only actors at play. A third layer, the middle tier, is equally important as the first two, but perhaps less visible. The middle tier is composed of several different professional profiles, varying greatly from country to country: district officials, system leaders, coaches, supervisors, and teacher mentors. They operate at the regional, district, and sub-district levels – in the buffer zone between the central level and the school level – and for this reason, they are instrumental in successfully translating reforms and new educational policies into practice.

A recent symposium during the September 2021 UKFIET conference on the subject, titled “Beyond the frontline: Strengthening instructional leadership and agency at the middle tier”, was aimed at shedding light on the role of this crucial part of the education system in transforming teaching and learning outcomes. The panel brought together IIEP-UNESCO, Education Development Trust, the University of Toronto, STiR Education, VVOB – education for development, Education.org and RISE.

Research has neglected the middle tier

A systematic review of the existing literature on the middle tier by the University of Toronto, covering both quantitative and qualitative approaches, draws attention to the significant, and yet unexplored, capabilities of this layer of education. “The middle tier until quite recently was neglected, both in empirical and experimental design research and in qualitative and leadership research”, says Karen Mundy, Director of IIEP-UNESCO. However, research on the middle tier has picked up new steam over the course of the last few years, and it is showing promising signs of growth. According to Mundy, one of the keys to advancing in this field will be to ensure a more balanced spread of research across geographies and different types of education systems. Most of the research has come from high-income countries. But existing gaps in methodology and the volume of publications are not necessarily negative aspects: we could benefit tremendously from tapping into the underrepresented “missing middle” realm.

How does the middle tier drive change?

Evidence emerges from a study conducted by IIEP-UNESCO and the Education Development Trust on instructional leaders at the middle tier in Delhi, Jordan, Rwanda, Shanghai, and Wales. Barbara Tournier from IIEP-UNESCO points out that these middle tier professionals can be true agents of change. Working closely within and across schools, instructional leaders are providing support for teaching improvement and promoting professional collaboration. They also take on the task of brokering knowledge to drive best practices, providing local instructional direction and system alignment at the same time. It emerges that testing innovations and scaling up best practices in these cities and countries would be much tougher without the framework provided by instructional leaders. According to the experience of Charlotte Jones, Global Head of Research and Development, Education Development Trust, in Jordan, the middle tier is also instrumental in effecting behavioural change in educational systems: “What we saw as a common theme at the middle tier was that supervisors were playing the vital role of evidence broker in helping practitioners to make sense of evidence to make better decisions”.

Examples from the field

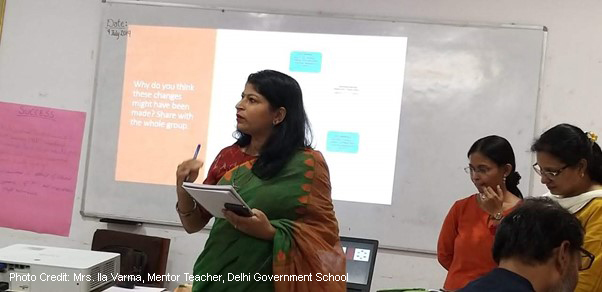

The Teacher Development Coordinator (TDC) programme conducted in Delhi, in partnership with the Government and STiR Education, is centred on delivering a support and collaboration system for teachers. The primary focus of the programme lies in developing the mindsets and behaviours of Mentor Teachers, Teacher Development Coordinators and district officials to build an effective support mechanism for teachers in schools.

The organisation saw, as a positive outcome of this support mechanism, a clear cultural shift at the school level. The organisation representative remarks that teachers and mentor teachers are more open to discussing innovative ways to address challenges that may arise among students. And not only that: they observed there is an increase in how district level officials are now promoting teacher collaboration and peer learning among teachers, wherein they are seeking each other’s advice and sharing best practices, for example by inviting fellow colleagues to observe classroom teaching. Neha Gehlot from STiR Education credits much of this improved educational environment to the role of the middle tier officials, who have helped schools and teachers along the way, as they systematically visited schools, routinised classroom observations for providing developmental support to teachers and gave feedback, coaching and mentoring with the aim of improving learning practices.

Another piece of evidence relative to the importance of middle tier officials in education systems comes from Zambia. VVOB, together with TaRL Africa developed the Catch Up programme using the Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) methodology. This system acts upon different levels of the educational environment, but its main focus is to drive effective mentoring and training for the workforce at the middle tier level. Catch Up, says Anna Murru, Partnership Manager at VVOB Zambia, is highly effective in harnessing the existing workforce to form teams of master trainers: candidates either come from the Ministry headquarters or the provincial or zonal levels and gain their badges through a series of methodology seminars and 20 days of in-classroom practice. After the initial training phase, the officials are then ready to pass on their knowledge to teachers and other school-based workforces in the country and support their work as they implement the methodology with the learners.

Making a case for investing in the middle tier

A number of governments globally are already investing in various ways at the middle tier level, but why should they be doing more? The answer is to be found in the promising results borne by programmes aimed at the middle tier workforce: policy-makers should be aware of the quality of the work being carried out and continue to support it. As Charlotte Jones reminds us, “most systems already invest quite a lot in the middle tier workforce. What is needed is to harness that potential and untapped resource to better serve teaching and learning outcomes”. Moreover, the middle tier has embedded training features that allow education systems to empower officials. “I think that empowerment is the key word, they feel empowered to support the teachers from their own experience and they get the recognition and respect because of that”, says Murru.

A fundamental argument in favour of investing in instructional leaders at the middle tier is that they can reset priorities around learning. As both Mundy and Yue-Yi Hwa, a Research Fellow for RISE, recognise, education systems face key tensions between upward accountability and the ability to problem-solve and iterate, especially around instructional improvements. Alignment and direction provided by the middle tier around a shared sense of purpose serve to counterbalance the predominance of accountability processes.

Beyond instructional leaders, other roles in the middle tier deserve accrued attention from ministries. Another opportunity for investment, says Tournier, lies in human resources managers at the middle tier, as education systems would thrive on better and more efficient workforce management.

There is a growing body of evidence, coming from both academia and on-the-ground practitioners, that the middle tier is increasingly instrumental for well-functioning education systems. Even though this specific field has long been overlooked in research in low- and middle- income countries, several successful scale-ups demonstrate the vital purpose of the middle tier. Be it improved educational environment, enhanced educational outcomes for students, or increased sense of ownership among the school level workforce, middle tier professionals will continue to make the difference. Speakers at the UKFIET symposium made the point clear: governments and policy-makers should take the opportunity to back this long-neglected layer with further investment.

Contributors to the UKFIET symposium, September 2021

Speakers: Professor Karen Mundy – University of Toronto & IIEP-UNESCO; Ms. Barbara Tournier – IIEP-UNESCO; Ms. Charlotte Jones – Education Development Trust; Ms. Neha Gehlot – STIR Education; Ms. Anna Murru – VVOB.

Chair: Dr. Suzanne Grant Lewis – Education.org.

Discussant: Dr. Yue-Yi Hwa – RISE Programme.